Mark Barry sets out his priorities for rail investment in Wales

In May 2018 the Cabinet Secretary for Economy and Transport, Ken Skates, announced that I would lead a programme to explore the strategic case for rail investment in Wales. The Cabinet Secretary also noted his priorities:

“…improving connectivity and reducing journey time between cities in Wales; expanding the city region areas across Wales; growing cross-border economies; enhancing connectivity from Wales to London; improving access to airports; maximising the potential benefits and offset negative consequences of High Speed 2 (HS2); providing compelling journey choices to users of the congested M4 at Swansea; and meeting trans-European network standards.”

Since then I have been working with Welsh Government officials, stakeholders and others to explore the potential wider benefits that could be realised; an initial summary of that work was published in July; an update and more comprehensive details were published on December 11th 2018.

The emerging reality is that although new improved rail rolling stock will be delivered and operating across the UK over the next few years, disappointingly, these vehicles will only be able to operate in “2nd gear” at best in Wales.

For example, the new Intercity Express Trains (IET) being rolled out for GWR services between Swansea and London are capable of 140mph and whilst they operate at 125mph between Bristol and London, they will only be able to operate at typically 90mph or less between the Severn Tunnel and Swansea. The line speeds and capacity of the north Wales mainline is also similarly constrained. For the two mainlines in Wales to be restricted in their capability in comparison with the mainline railways elsewhere in the UK is at best questionable and points to an institutional weakness in the process that determines rail investment in the UK.

Earlier in November 2018, Network Rail (NR) confirmed that in the period 2019-24, it would be spending just under £2bn on operations, renewals and maintenance of the Wales route. Whilst welcome, that figure is about 6% of the total of £35bn across the UK as a whole, for a part of the network that represents 11% of the UK total.

However, this investment does not include enhancements (which are typically focussed on improving network capability, reliability and capacity) and the stark fact is that the Wales route (11% of the UK network) has not received an equitable proportion of UK rail enhancement investment over many years. Since 2011, the figure has been a little over 1% of the UK total and this disproportionally low level of enhancement investment actually goes back much further, decades in fact, as a review of Network Rail’s historical High-Level Output Specifications will demonstrate.

This at a time when the UK is committing £56bn to High Speed 2 (for which there is no Barnett consequential for Wales as there is in Scotland, which actually benefits from the scheme), potentially £30bn to Crossrail 2 in London, and £70bn to Transport for the North over the next 30 years to deliver major schemes like Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR). I originally raised the issues related to HS2 and its economic impact on Wales in my submission to the Westminster Transport Committee’s review of High Speed Rail in 2011.

I also believe that there exists a fundamental bias impacting the method by which rail enhancement investments are determined across England/Wales by the Department for Transport (DfT) in London, which has responsibility for such matters on an England and Wales basis. It would appear some parts of the network have been locked into a virtuous circle of ongoing enhancement whereas some parts have been completely overlooked over many years. It’s easy to see why: investing in more reliability and capacity generally leads to more demand and so pressure on capacity and reliability, leading to a stronger case for further enhancement investment. If your network is not on this “enhancement conveyor belt” or has a smaller economic case for enhancement it will always get swamped by the big-ticket items. As any business knows, when making investment decisions, you have to assess the state of the capital assets on your balance sheet as well as the impact on the P&L account. You can’t compete and maintain margins if you operate on depreciated assets when compared to your competitors.

It is also an accounting oddity for DfT/NR to have historically apportioned the debt accruing from its investment in enhancements evenly across the UK rail network (manifest in its regulated asset base) with limited reference to where that debt was actually used to enhance or renew the network. That means in crude accounting terms, the Wales route has been allocated the costs used to fund enhancements elsewhere in the UK – which will result in an over valuation of the Wales rail asset! I suspect this issue will complicate potential future network transfers once the core Valleys line transfer, as part of the South Wales Metro, is concluded. Rail accounting is a very complex subject – so I will leave others to provide a more informed view.

All these factors explain why investment in Wales’ rail network has fallen so far behind other parts of the UK.

The result is a less efficient railway with lower capacity in Wales versus the UK as a whole, leading to lower demand and higher subsidies per passenger; more worryingly it is also having a detrimental impact on the Welsh economy.

My conclusions, which are consistent with the findings of both the Welsh Affairs and Transport Parliamentary Select Committees at Westminster, is that enhancement investment is needed, is justified and can deliver economic benefits; the initial proposals set out in my work for Welsh Government could contribute, conservatively over £2bn to the Welsh economy.

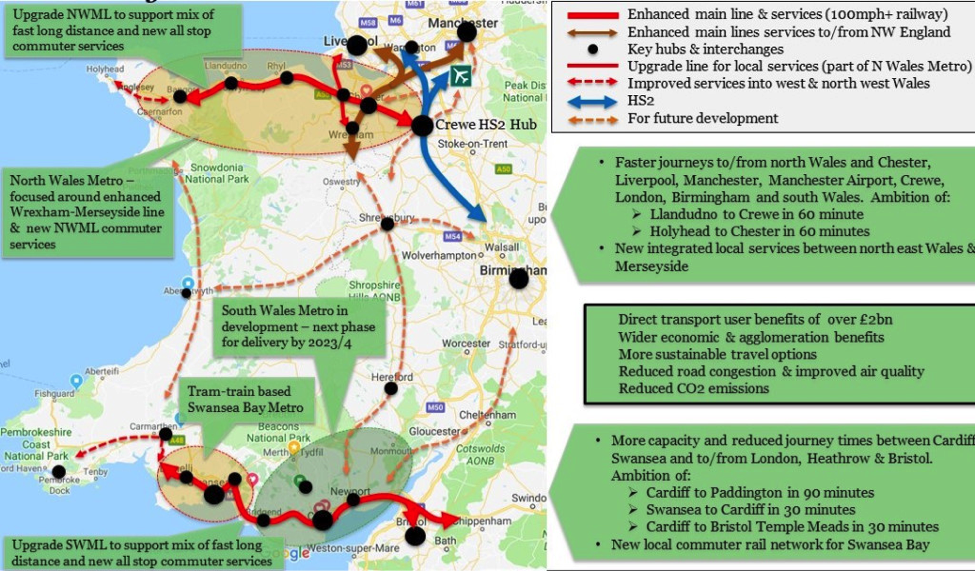

Wales’ economy needs faster and more frequent services between its major towns and cities and to other key UK commercial centres such as Bristol, London, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds and Liverpool as well as to major international gateways like Heathrow and Manchester airports. Our ambition is to see journey times of: Cardiff to Paddington in 90 minutes, Swansea to Cardiff in 30 minutes, Cardiff to Bristol Temple Meads in 30 minutes, Holyhead to Chester in 60 minutes and Llandudno to Crewe in 60 minutes.

More than that, given our shared environmental responsibilities and the need to address issues of road congestion, especially air quality impacts, we need to develop a viable and affordable alternative to the car. Whilst rail does not currently serve all parts of Wales it does cover a large and growing proportion of our population. Therefore, investment in rail infrastructure aligned to future innovations in traction power will enable us to travel when required, more sustainably in future and at the same time provide essential enhancements to a key part of our country’s economic infrastructure. The vital role of bus services and active travel modes cannot be overlooked; whilst not a focus of my recent work, they are vital elements an integrated public transport network for communities all over Wales and often provide an important part of the total end-to-end journey alongside rail travel.

I believe Wales’ immediate priorities for rail investment (Figure 1) are:

- The main lines in north and south Wales should both be capable of at least 100 mph and have sufficient capacity to operate faster long distance and additional local all-stop services.

- The connections from West Wales through Swansea, Cardiff and Newport to Bristol are perhaps the most important in this regard – especially given the increasing profile of the “Western powerhouse”. In fact, the potential agglomerative economic benefits often discussed are being constrained by the current poor rail connectivity; this requirement is as important as the proposals to improve the M4 around Newport. Major commercial development such as that proposed at Cardiff Parkway, and the potential of Swansea city centre will also be enhanced by such improvements to our rail network.

- The ongoing implementation and development/expansion of the South Wales Metro and the development of a Swansea Bay Metro and potential parkway in West Wales; Swansea Bay’s economy is constrained in part due to its lack of a dedicated commuter rail network.

- Upgrade of rail services in NE Wales and especially Wrexham to Merseyside (via Bidston) as part of a north Wales Metro and links connection through Chester to the HS2 hub at Crewe and to Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool.

Figure 1 Emerging priorities for rail investment in north and south Wales

As important, I think it’s a glaring devolution anomaly that the Welsh Government does not have responsibility for rail infrastructure in Wales. It is overwhelmingly clear that the current England and Wales arrangement, under the stewardship of the DfT in London, has not served Wales well. Full responsibility to develop and implement schemes in Wales must fall to the Welsh Government and in doing so the UK Government must recognise that sufficient funding needs to be transferred to discharge these responsibilities and to address many years of “underinvestment”. The UK Government has already established similar arrangements via Transport for the North, and Scotland secured this arrangement, which included a block grant adjustment, over ten years ago. Is it too much to ask for Wales to get the same treatment?

This article first appeared in the Western Mail

Photo by Cory Woodward on Unsplash

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.

Comments are closed.