Geraint Talfan Davies analyses Wales’s efforts to increase its international presence and questions the recent Welsh Government reshuffle.

Until the arrival of Covid-19 it was Brexit that was destined to end up as ‘the great disruption’.

Now it has a much bigger rival for that accolade. The coronavirus has changed the world context utterly. Whereas six months ago one could, arguably, have a debate as to whether other world markets offered us a realistic alternative to the European market that we are due to exit, now we face exiting the EU into a world that is facing the biggest depression in a century. Big new lifeboats are nowhere to be seen.

This has massive consequences for the whole of the UK but especially for its poorer parts, in which we must, sadly but predictably, include Wales. You cannot rip up four decades of ever-increasing inter-twining of our economy with those of our erstwhile European partners without a degree of pain, but it will be even harder to try to knit together compensating new relationships in a howling global gale.

One must feel for Baroness Eluned Morgan. Last December she was scarcely more than a year into her newly created post of the Welsh Government’s Minister for International Relations and the Welsh Language, when she published her international strategy, an embryonic Welsh foreign policy, only to see it overtaken by a world pandemic.

Last week the pandemic went the whole hog and stripped her of that responsibility, returning it into the hands of the First Minister, while she is asked to assist the Minister of Health Vaughan Gething, by taking on responsibility for mental health.

Given the pressures, this sudden switch is understandable, but one hopes it only a temporary change, for the international brief is too important to have to fight for the attention of a First Minister already juggling so many balls. There is a history to this issue.

We had to wait 20 years for the creation of Eluned Morgan’s (previous) post, a delay that had always been difficult to explain, especially since the Scottish Government had a Minister for External Affairs within a year of the inception of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

“It would be easy at any time to dismiss an international strategy for Wales as a cork on an ocean wave, but this one was launched in a truly forbidding climate.”

It may have been that our previous First Ministers, Rhodri Morgan and Carwyn Jones, relished the international ambassador role, the latter perhaps even more so than the former. After all, Carwyn Jones had been instrumental in pushing for the abolition of the Welsh Development Agency, penning a ‘Gregynog Paper’ on the issue in 2003 for the Institute of Welsh Affairs.

But neither can be said to have published a detailed international strategy, although a 2015 document during Carwyn Jones’s tenure claimed to provide ‘a framework’.

Mark Drakeford, as well as facing the prospect of Brexit, also had to find a role for Eluned Morgan whose credentials for the post must have seemed tailor-made for an international brief: two years at the international Atlantic College at St. Donats, a degree in European Studies and 15 years as a Member of the European Parliament where she was the Labour Party’s spokesperson on energy, industry and science.

Comparisons with the comparable Scottish post are instructive. There, for the most part, the international brief (designated External Affairs) has been paired with responsibility for culture, one of the lighter ministerial briefs.

The same pattern has been followed here in Wales – combining international relations with responsibility for the Welsh Language, culture, tourism and sport. In both countries the load has been shared with Deputy Ministers.

But there is a difference. In Scotland’s Cabinet, Michael Russell, has responsibility not only for external affairs but also for the constitution and for Europe. His deputy is designated Minister for Europe and International Development, creating a strong European focus in the two posts. In Wales, the Deputy Minister, Lord Elis-Thomas, leads on tourism, culture and sport.

Although the list of Eluned Morgan’s responsibilities includes ‘Wales in Europe’ the person who leads on this issue for the Welsh Government is the Counsel General, Jeremy Miles, the designated Brexit Minister, a role that takes in issues relating to the EU structural funds as well as the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (remember that?) that is scheduled to replace them. He also chairs the Cabinet Sub-committee on European Transition.

The difference between the external briefs in both countries may be accounted for by the fact that Wales’s Counsel General cannot exercise powers conferred on Welsh ministers. According to a public note, Jeremy Miles’ role involves policy advice and coordination, but “any matter requiring a formal decision of Welsh Ministers under a statutory power will be exercised by the First Minister or a nominated portfolio Minister.”

That said, there is no doubt that the task of shaping an international strategy had, until last week, lain squarely with Eluned Morgan. It would be easy at any time to dismiss an international strategy for Wales as a cork on an ocean wave, but this one was launched in a truly forbidding climate.

To change the metaphor, it is not that Wales has a mountain to climb, rather a whole range of mountains, all made steeper by coronavirus.

“The tourism budget in Wales was £16m, against Scotland’s tourism budget of £45m.”

First, there are the hard facts of the scale of change. We have been inside a big tent – competing with our EU partners, yes, but also sharing values and common rules. We have operated within a secure framework, part of a continental entity that has massive commercial clout in the world.

UK Government Ministers, especially those of more ideological bent – and there is no shortage – will tell us not to worry. After all, the UK is the sixth largest economy in the world.

But numbers matter and however you look at it, whether from beneath Dominic Cummings’ dome or through our Prime Minister’s imperial nostalgia, 60 million is a lot less than 500 million – in fact, about one eighth. That’s not a difference businesses will ignore, however much ideologues would like to wish it away. Proximity also tells.

Second, this is a very competitive environment. The Scots and the Irish have always had more clout than Wales in the international field because of relative size, history and budgetary headroom.

In 2019-20 the Welsh Government’s budget for international relations and international development was £7m, set against the equivalent Scottish budget of £24m. Similarly, the tourism budget in Wales was £16m, against Scotland’s tourism budget of £45m.

In 2020-21, despite a very significant increase of £3m (40%) for international relations and development, the gap (pre-Covid) was planned to close only slightly, with the Scottish figure also rising by £2m.

Strangely, none of the £3m increase in the Welsh spend was to be devoted to more boots on the ground as the Welsh Government has been operating a freeze on staff numbers. It is not clear whether there has been any redeployment of staff. Even so, the disparity in overseas staff numbers between the two countries is likely to be as stark as the budget differences.

Comparisons with Scotland – that can be made in many fields – are usually dismissed by Welsh Government ministers who can justifiably point to Scotland’s greater size and to the more generous treatment given to it under the Barnett formula. A parallel generosity has been shown to Northern Ireland in the interest of peace. Nevertheless, such examples of force majeure convey an undoubted advantage for those two countries in the international marketplace.

A third Brexit-related challenge will come from Ireland, a country that will now be a more effective competitor, enjoying continued protection from the EU over and above the continued benefits of single market membership as well as the benefits of Ireland’s controversial lower corporation tax.

“Given the scale of increase in more recent years, targeting a 5% increase over the next five seems unduly modest.”

The Irish Government spends close to €800m on Foreign Affairs and was scheduled to add another €54m to that budget this year. The UK Government’s decision to shape a new border down the Irish sea will surely mean that Northern Ireland will enjoy further spin-off from its southern neighbour’s spend.

Add to these the UK Government’s new concentration on helping the north of England, as well as that region’s increasing efforts to shape its own destiny, and one can see that Wales has an awful lot to do to be an effective competitor even with its UK and Irish rivals.

So, putting aside the budgetary constraints (which will almost certainly have to be revisited given the effects of the epidemic on the public finances); how does Wales’ new international strategy stand up to these challenges?

The first plus must be the fact that we have a strategy at all and, until last Thursday, a minister to go with it. But that would be to damn it with faint praise. Apart from the 40 per cent increase in budget, the strategy has a strong values base – centred on Welsh creativity, technology and commitment to sustainability – set in the context of Wales’s pioneering Well-being of Future Generations Act. The document’s main focus is, of course, economic but, thankfully, it does not ignore the role of culture and sport in flying the flag for Wales internationally.

Its three overall aims are to raise the profile of Wales, to grow the economy through increased exports and inward investment and to establish Wales as a globally responsible nation. On the business and research front it wants to focus on three areas in particular: cyber security, compound semi-conductors and the creative industries.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

Some business people would have liked that list to be longer, but those who in the past have criticised the government for failing to prioritise can hardly complain.

Where the document shares a common failing with other Welsh Government strategy documents is the relative absence of numbers and, I would argue, an excessively rhetorical style – as if we first have to convince ourselves.

Although there is a fair amount of data about current performance in its 40 pages, I could find only two numeric future targets: an aim, over the next five years, to increase exports by 5% from the current level of £17.2 billion, (implying an increase of £860m.) and to increase contacts amongst the worldwide Welsh diaspora to 500,000 (although it does not state the current level of contacts).

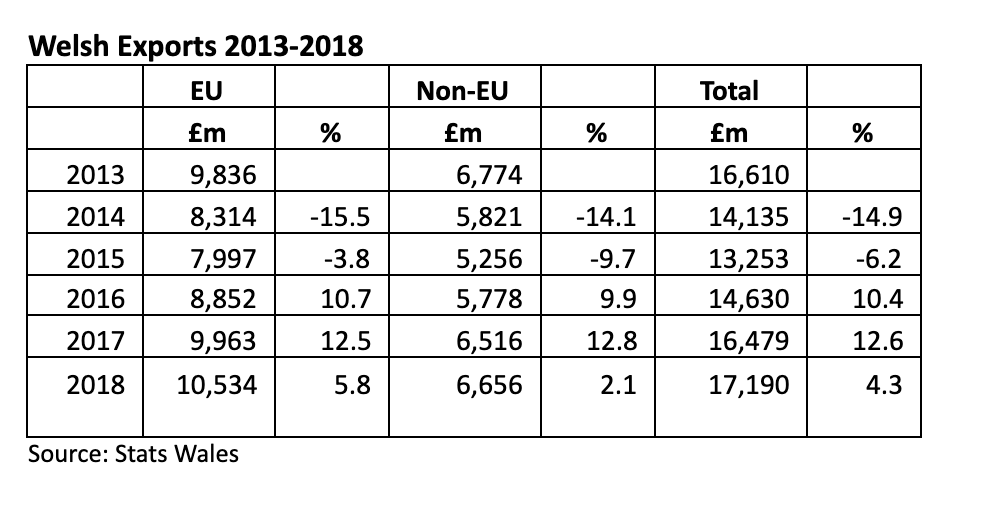

In the days before coronavirus the targeted 5% increase in exports over the next five years would surely have seemed low given that, over the last three years, there had been a 29.7% increase in exports from Wales: 2016 +10.4%, 2017 +12.8%; 2018 +4.3%. These three years did follow two years of decline: 2014 -14.9%, 2015 -6.2%, so that taking the five years together the overall increase was only 3.5%.

But, given the scale of increase in more recent years, targeting a 5% increase over the next five seems unduly modest unless it assumes either a massive hit from Brexit, continuing volatility in export performance or, now, a new global depression.

Interestingly, the export data does not suggest any different trends in export performance in EU and non-EU markets, nor any shift from the former to the latter.

If one compares 2013 with 2018, there has been a 7.1% increase in Welsh exports to the EU and a 1.7% decline in our exports to non-EU countries. Interestingly, the biggest percentage increase over that five years was in exports to West European countries outside the EU (48%), reinforcing the argument for the importance of proximity.

Another striking feature is that when you combine exports to the EU with those to other European countries outside the EU, the European share of total exports has risen marginally but consistently in each of the last four years. In 2013 it stood at 62.5% of the total, rising to 65.2% in 2018.

Where the document could have been bolder on exports, it promises a new approach to the diaspora – a concept that too often invokes heady unrealism. Much depends on how the diaspora is defined.

If we are talking about the descendants of people who emigrated from Wales in the 19th and 20th centuries, Wales cannot claim a diaspora on anything like the scale of Ireland or Scotland. When, in the 19th century, the Irish fled their famine and the Scots their highland clearances, Welsh people congregated instead at home in the coal mining valleys.

It is the resulting disparity in emigration numbers that meant that, in the USA, the Welsh never developed the powerful and coherent political lobby that the Irish, and to a lesser extent the Scots, can mount even today.

On the other hand, the notion of a global Wales network of active connections and influence is one that has long needed more systematic organisation. It can build not only on past migration but also on the experience of post-war decades of foreign direct investment in Wales, existing trade, international academic research, and cultural connections.

The Welsh Government has commissioned the Alacrity Foundation – an offshoot of Sir Terry Matthew’s empire – to find a method of harnessing the diaspora. In a field often dripping with sentiment, a hard-headed approach will be welcome.

This is only to pick out two issues in a document that is wide-ranging and thoughtful although, as I have suggested, could do with more hard numerical targets.

The effects of the Covic-19 epidemic will no doubt require fresh policy assessments to be made as we emerge from it, not least given its likely longevity. That is yet another reason why we need a longer transition period.

The Welsh Government desperately needed space to assess what changes may be needed in its international strategy post-Covid. Let’s hope that last week’s shuffling of responsibilities does not disrupt that process.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.

This is an updated article originally published in the Welsh agenda #64.