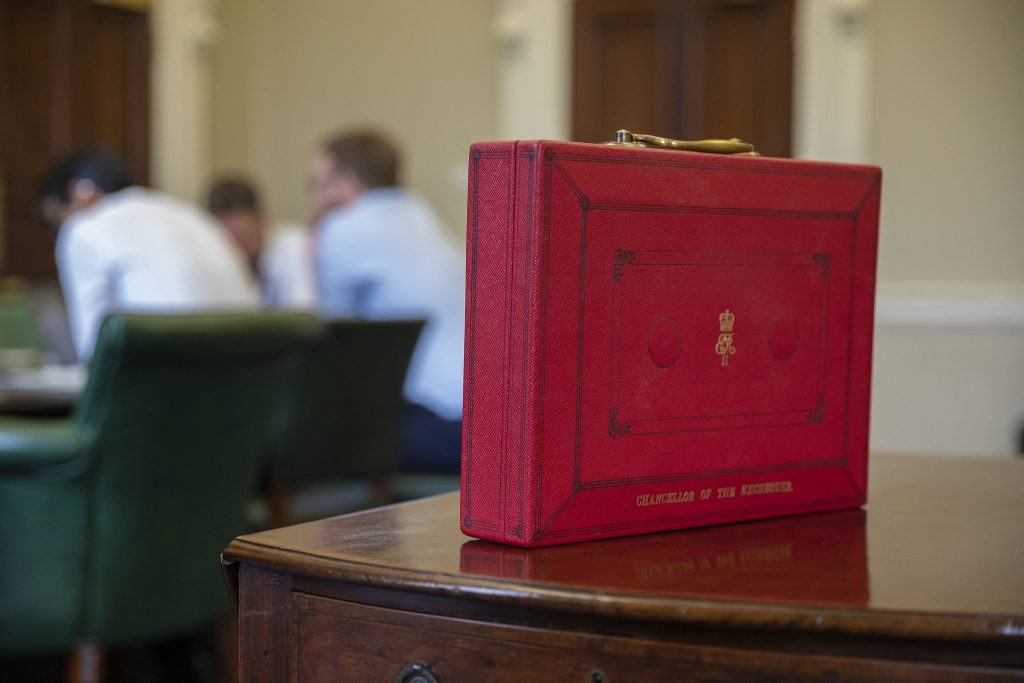

Dr Jack Watkins offers an analysis of the UK Government’s 2021 Budget announcements and its impact on Wales.

This year’s UK Government Budget and Spending Review announcements represented something of a return to normality after an exceptional two years for the public finances. Nonetheless, many will be pleased to see that this new normal includes increases in spending across government and across the UK. One thing that is not normal is HM Treasury’s new role as a funder through the Levelling Up Fund, including 10 projects in Wales.

Here are our key reflections on the budget and what it means for Wales.

An uplift in public spending

The Budget announcement includes an additional £2.5bn per year on average for Wales, from now to 2024-5. This is calculated through the Barnett Formula, and therefore is informed by comparable increases in England. This will undoubtedly provide welcome clarity and will give the Welsh Government, local authorities and health boards a greater opportunity to plan ahead for spending on essential public services.

‘These differences in approach to fiscal policy reflect the politics of a pro-devolution Welsh Government on one hand and an increasingly ‘muscular unionist’ UK Government one the other…

However, while there have been fairly bold proclamations about what this represents in terms of public services and even the philosophy of the Conservative Party, it needs to be considered in a wider context. Looking back to 2019-20, before COVID-19 and the extraordinary public spending needed to address it, a £1.1bn increase in the Welsh Government budget was rightly seen as the end of austerity, but the reality is that neither of these increases take us to where public spending would have been if not for the significant cuts of the last decade.

The Treasury announcement is therefore welcome, representing a recognition of the impacts not only of the pandemic (which the OBR now claims were less than expected) but also of the previous decade in which spending fell despite rising demand for services, particularly health and social care. However, no one should be given the impression that this will result in any transformative impact; many essential services will continue merely to tread water.

Tax, not borrowing

The uplift in public spending comes alongside a commitment to keep borrowing down. This represents a political decision rather than a fiscal necessity. In the immediate term, it means that increased spending comes alongside the biggest increase in general taxation since 1993. Tax as a proportion of national income is now the highest it has been since the 1950s, when the UK was paying off its significant war debts, building its welfare state and managing a range of government-owned industries.

The impact of the increase in tax is likely to be felt more keenly by some than others. Middle income households will be hit hardest, and university graduates, through a combination of tax rises and student loan payments, are also facing marginal tax rates rising to 50 percent.

The choice to tax rather than borrow is also controversial given the remarkably low costs of borrowing for the UK Government. Here, there is evidence that the Treasury and the Welsh Government have a difference of opinion. Having created a tax authority and been granted tax raising powers in 2019, the Welsh Government has indicated multiple times that it prefers the option of increasing its borrowing capacity to pay for capital spending, and remains cautious about the use of its tax powers. The Treasury seems to take a different view.

Gofod i drafod, dadlau, ac ymchwilio.

Cefnogwch brif felin drafod annibynnol Cymru.

These differences in approach to fiscal policy reflect the politics of a pro-devolution Welsh Government on one hand and an increasingly ‘muscular unionist’ UK Government one the other, which appears to have adopted a policy of a blanket ban on further powers for devolved nations. At the same time, they also reflect a difference of opinion between a Labour administration that wants to use low borrowing rates to invest in the economy, and a Conservative administration that ostensibly prefers to keep tax, borrowing and, ultimately, spending low.

‘It seems that the UK Government is hoping that people will make the right choices without taxation guiding them. As the OECD and IMF have noted, it is not clear that this approach will work for curbing the Western world’s excessive emissions.

Much of the Welsh Government’s budget is essentially ‘pre-spent’ due the need to deliver a nation-wide healthcare service, schools, transport systems and much more. Borrowing can provide spare fiscal capacity to invest in future growth (which if done well can more than pay for debts incurred) via enhanced infrastructure, education, and on necessary changes such as getting ahead on decarbonisation. While the Welsh Government has not always used its borrowing capacity to its full advantage, it is disappointing that this capacity remains considerably constrained.

A COP-out on climate change

The world’s leaders will arrive at COP26 next week looking to the UK to play a leading role not only in the climate summit but in the future trajectory of global decarbonisation. Anyone looking to travel to Glasgow from Wales may soon find it cheaper to fly there, following the announcement that Air Passenger Duty for domestic flights will be reduced. In a week when both the Welsh and UK Governments are drawing attention to their strategies to meet the 2050 and 2035 targets, the Treasury has gone back on plans to raise fuel duties.

As Jill Rutter, formerly of the Treasury and now of the Institute for Government, has noted, refusing to tax carbon emissions places the burden of emissions reductions on other government departments, who can only use subsidies and regulation. It seems that the UK Government is hoping that people will make the right choices without taxation guiding them. As the OECD and IMF have noted, it is not clear that this approach will work for curbing the Western world’s excessive emissions.

A centralising tendency

‘Is it possible to have a ‘Welsh’ economic strategy, now that so many investments will be led from London?

In addition to the £15.9bn baseline funding and the £2.5 billion increase through the Barnett Formula, the Treasury is also spending £425 million in Wales through other funding streams. This is not unusual where it relates to reserved powers and other forms of UK-wide spending. But what is notable about this budget is that the UK-wide spending now covers a wider range of activities, with around £121 million annually through the Levelling Up Fund and other direct investments through grants to farmers, support for regeneration and the Community Ownership Fund.

With European funds coming to an end, and the UK Government being clear that their replacements will be awarded from London not Cardiff, we can expect these kinds of projects to become a regular feature of future budget and spending review announcements.

There are evidently some key questions about what this new reality means for the devolution settlement. Is it possible to have a ‘Welsh’ economic strategy, now that so many investments will be led from London? What happens if, for example, the Welsh Government wants to deter car use and switch to public transport and active travel, whilst UK Government supports use of electric cars and wants to expand the road network? All of these questions will need to be addressed over time – something that we will be picking up in more detail through the IWA’s forthcoming Economy Summit at the end of November. But having reflected on this budget there are also questions about what this means for the Treasury and its place in government.

Historically, the Treasury’s role has been to collect money and distribute it to departments. Its influence on policy was enormous, but largely indirect. With these new investments coming directly from the Treasury, it is extending its policy making capacity and taking on a new role distributing money directly to projects.

On a basic level, it seems bizarre that decisions about whether to fund a roundabout in Falkirk should rest with a team of officials in the Treasury rather than with the Scottish Government and Falkirk Council. And why Falkirk rather than, say, Cwmbran? The methodology for the Levelling Up fund has left many people confused and unable to scrutinise the Treasury’s decisions – leading to justified criticisms of apparent ‘pork-barrel’ politics.

Accountability

‘Worryingly, the Treasury’s approach to this budget raises concerns that as a Department it is attempting to evade scrutiny on the less palatable parts of its agenda.

With the Treasury now delivering directly in Wales and elsewhere, important questions arise about how its decisions will be scrutinised. The Treasury faces scrutiny on the floor of the House of Commons and through its Select Committees, notably the Treasury committee. But much of this scrutiny is built on the idea of the Treasury as a funder, not a do-er. Delivering projects directly will require formal evaluations and analysis, and elected representatives to hold Ministers and officials to account.

The patchy and informal nature of inter-parliamentary relations limits the potential role of the Senedd in scrutinising these kinds of investments in Wales by UK Government – something we have previously highlighted as a weakness in our democracy. The upcoming cut in the number of Welsh MPs will not only cut Wales’ potential allocation of the Levelling Up Fund (with each MP getting one bid), but will reduce the capacity to raise questions about how it is being delivered.

Worryingly, the Treasury’s approach to this budget raises concerns that as a Department it is attempting to evade scrutiny on the less palatable parts of its agenda. Briefing aspects of the budget in advance – such as the increase in National Insurance – had the notable effect of reducing their prominence in media coverage. The Speaker of the House of Commons has rightly condemned the Treasury’s actions in briefing other aspects of the Budget earlier this week before briefing the House. But the response of Simon Clarke MP, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, suggests that this was entirely purposeful, trailing announcements in order ‘…to help communicate to the public what we’re doing with their hard earned money.’

This response suggests that the UK Government has learned an important lesson from Brexit – that an appeal to the ‘will of the people’ can provide cover for subverting established procedures. Some argued that this messy insertion into the UK’s complex constitutional arrangements was always intended to be a one-off to cut through the Brexit stalemate, but the actions of the Treasury suggest that it could become more permanent. This could have worrying implications for a parliamentary system that is ultimately reliant on unwritten rules and on the good behaviour of its leaders.

We will be discussing the budget, ‘levelling up’ and COP-26 in more detail at our 2021 Economy Summit. Join us over 2-days from 30 November to 1 December as we hear from experts on the issues facing Wales’ economy in a post-Covid-19 world.