In this review of Tôpher Mills’ selected poems, Nia Moseley-Roberts reflects on the ebb and flow of a collection brimming with life.

You quickly get the sense that Selected Poems was never going to be an acceptable title for Tôpher Mills’ collected work: Sex on Toast is a much punchier name for a greatest hits album, and one which matches the bravado of its writer.

Mills is one of Cardiff’s most familiar voices: poet, journalist, and publisher, a stalwart of the Welsh literary scene. The danger of so bold a title, however, is that it risks obscuring the range and sensitivity of the poems it encompasses. At 288 pages, this is a long collection, something reflected in the breadth of Mills’ subject matter, from childbirth to the Hay Festival (and yes, there is also some sex).

Themes are explored, put down, and then picked up again later in the collection, allowing a sense of Mills’ poetic development to rise out of natural comparison.

In his foreword, Mills states that he has ‘put together a collection that flows and gives some idea of how my poetry has developed so far’, a statement which could be made true by replacing ‘poetry’ with ‘life’. For Mills, the line between the two is thin to non-existent, the man the matter of his poetry, the poetry standing for the man. The period for which this is complicated – the time in which Mills’ life and Mills’ writing did not flow together, because the writing had not yet begun – is childhood, which Mills has represented through collecting poems into Sex on Toast’s first section, ‘Early Life’. Following this come a series of chapters roughly tracking Mills’ poetic career, sometimes with more local rationalising forces; ‘Something’s Awry’, the section containing the titular ‘sex on toast’, is filled with love poems, sketching the arc of a relationship.

Sex on Toast’s tracking through Mills’ long career gives it a symphonic quality. Themes are explored, put down, and then picked up again later in the collection, allowing a sense of Mills’ poetic development to rise out of natural comparison. The finest example of this is the unemployment poem, where Mills is at his sardonic best. Whilst the emotions captured – anger, frustration, cynicism, and a laugh-or-you’ll-cry powerlessness – are fairly constant, the deftness with which Mills’ presents them increases through the collection. ‘Madoc at the Jobcentre’, the final unemployment poem, in which the legendary Prince Madoc, discoverer of America, is unable to get his skills recognised at the job centre, is brilliant.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

This collection’s key organising principle is Tôpher Mills. Mills’ centring of himself and his own experiences is a political act; as a working-class Cardiff man writing in English and dodging in and out of work, his is a voice which is not often heard. Whilst the majority of Mills’ poetry is simply representational, its representation of male working-class Cardiff life makes it radical, important, and worthy of attention.

Sometimes Mills’ honesty grates – I can’t say I enjoyed ‘Alas Poor Yoricks’, in which Mills rewrites Hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy as a complaint about the necessity of condoms in the AIDS crisis – but at other times it is humbling and powerful. ‘Temporary Dad’, on part-time parenting, and ‘Ducts’, in which Mills cries, are vital poems. However, many of the collection’s best and most touching pieces are on subjects which transcend class boundaries; Mills’ writing on his family, particularly his aging parents, is raw and poignant.

The pieces in ‘Early Work’ are lyrical, led by the ear, and outline experiences: the murdered lover, the summer cycle ride, the dockyard.

In his introduction, Mills describes how ‘I slowly became aware of how unusual I was in the world of poetry’, and this realisation, a rising self-awareness, shows in his work. Mills is interested in what it means to be a poet, part of a literary circle, positioned within a literary landscape. He describes going to festivals and readings, documenting the names and faces with which he grows increasingly familiar. Mills becomes a poet of community, constantly in dialogue with other poets, other poems, novels, and songs, his style characterised by an intertextuality often manifesting as parody.

In poems such as ‘Laureate’, which describes a reading by Ted Hughes, this works very well, and there are laugh-aloud moments. Other times (as in the aforementioned condom poem) the joke can feel overlaboured, and the reader is left wondering who exactly this is for. A growth in self-awareness for Mills comes with what I see as a decline in the quality of his poetry. The pieces in ‘Early Work’ are lyrical, led by the ear, and outline experiences: the murdered lover, the summer cycle ride, the dockyard. This is poetry for the sake of poetry, but once Mills begins to write more consciously about his life, as a poet, some of the clarity and song is lost, only to be regained later in the volume.

I stated above that this is a collection in which poetry and life blend together. When the man begins to dwarf the pen, this is not an advantage. Mills is at his best when he allows himself to fade into the background, to become a medium. ‘Tide Memory’ is such a poem. Looking across the bay, the speaker recalls old Cardiff, before the barrage; I never knew it, and to hear Mills’ recollections is a privilege. Sex on Toast is a notable landmark on the Welsh literary scene, essential reading for anyone seeking to understand working class Cardiff life – or simply seeking a laugh.

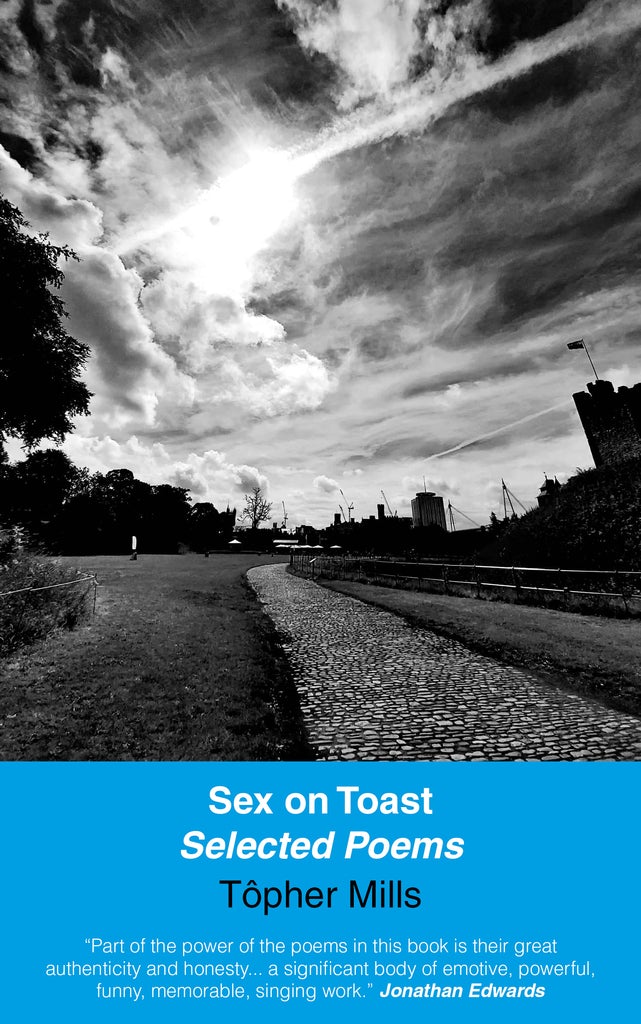

Sex on Toast

Tôpher Mills

Parthian, 2021

Available on Parthian’s website

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.