Sophie Buchaillard connects the Ukrainian crisis and the Rwandan genocide to think about the West’s contrasting relationship to refugees.

A few weeks into the war in Ukraine, our television screens were filled with images of dishevelled women and children crowding onto train platforms in a country not so distant from our own.

At the other end of their journey stood Poland and Germany, turned overnight into large-scale refugee hubs from which the rest of Europe operated pop-up schemes to welcome their share of refugees in an act of well publicised solidarity. Various news outlets made comparisons with the experience of the second world war. Everywhere, houses and official buildings were draped in blue and yellow, a visual symbol that we saw ourselves as one community.

At the same time, quieter reports came in from the Polish border with Ukraine where other asylum seekers were refused entry: African students attending university in Ukraine, trying to find their way home. I have published a number of essays on migration. Around that time, I was in conversation with a Francophone journalist from Burundi, Arsène Arakaza, about the online magazine that he and fifteen other journalists had set up to raise awareness of the ongoing refugee crisis in the Great Lake region of Eastern Africa. They were all in refugee camps. They had all read about the treatment of those African students compared to that of the Ukrainian refugees, and were surprised and angry that the BBC, in particular, would report on this crisis as if refugees were a new phenomenon. Arsène, you see, has been a refugee for eighteen years, bounced from one camp to the next, unable to return to his native country due to ongoing conflicts. Amongst his colleagues, some have been refugees for more than twenty years. When we spoke, he wanted to raise awareness in Europe of the dire sanitary emergency unfolding in the camps. No access to Covid vaccines there, he sighed, adding that not a single news outlet in Europe had expressed an interest in his story.

It is hard to comprehend why the heads of foreign governments and the United Nations waited, despite repeated warnings from neighbouring countries confirming a genocide was taking place.

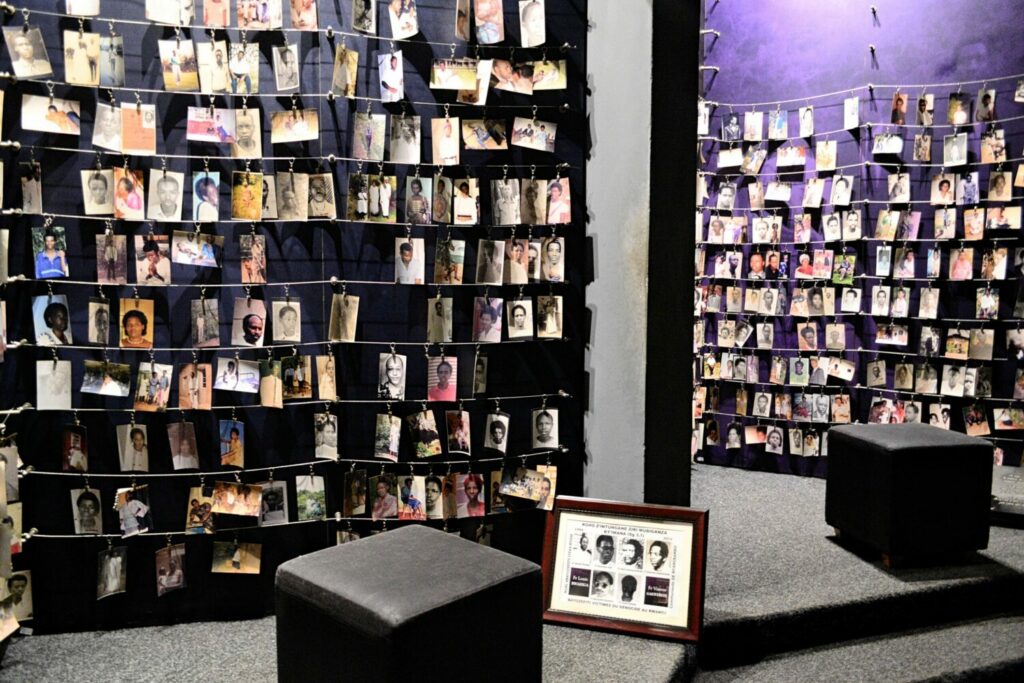

Over a quarter of a century ago, when I was sixteen years old, for a few months I corresponded with a girl of the same age named Victoria. She was in the refugee camp of Goma in Zaïre (now Democratic Republic of Congo), having fled her home in neighbouring Rwanda where a genocide had taken place in the spring of 1994, claiming the life of 800,000 people in just one hundred days. At the time, the international institutions set up after World War Two to prevent a repeat of the Holocaust were reluctant to declare a genocide until it was too late. They failed to apply any diplomatic pressure on the extremist government to protect populations on the ground. It is hard to comprehend why the heads of foreign governments and the United Nations waited, despite repeated warnings from neighbouring countries confirming a genocide was taking place. The appetite for action seemed to be lacking. Official reports mention a parallel with Somalia where factions had been fighting since 1991 in what was described as a stateless nation. Simultaneously, the international press reported a flash conflict between two ethnic groups in Rwanda, misusing the terms ethnic-Hutu/ethnic-Tutsi, reinforcing the impression that what was happening there was no more than a tribal conflict, rather than what would later be revealed as a well-orchestrated policy of racial hatred. The inference at the time was clear, though: it served to perpetuate existing Western biases towards former colonial subordinates, painting the sort of picture which continues to influence our perception of the Global South today.

The reality of Rwanda is very different, however. When the kingdom of Rwanda became a German protectorate in 1885, it had a complex ruling structure. The state was supported by an administrative network that oversaw three groups of people in a semi-feudal system composed of Tutsi, Hutu and Twa, terms which described the economic role of the people. Rwanda was organised in province, district, hill and neighbourhood.

After the First World War, the League of Nations gave Belgium a mandate over the country. Belgium eliminated existing structures which were replaced by forced labour across the country. At the same time, they introduced compulsory identity cards to control the population. Influenced by the division that existed in Belgium between Flemish and Walloon, the Belgian understood the terms Hutu, Tutsi and Twa as ethnic rather than economic groups, therefore engineering a racial division which had not previously existed, and giving Tutsi rule over the majority Hutu. It is this divide which extremists among the Hutu later sought to exploit after the 1961 independence. Immediately, they instituted a one-party system with a manifesto which called for the extermination of the Tutsi.

As early as the 1970s, reports exist of Tutsi being massacred and pushed across the border to Uganda. The growing propaganda against the Tutsi developed through state-organised newspapers and radio stations where dehumanising terms were increasingly used to refer to the Tutsi. Appropriating the racialist theories of the British colonial explorer John Hanning Speke, the Hutu extremists painted a picture of the Tutsi as foreign invaders, both at home and with international partners such as France. The latter was keen to develop ties with Rwanda, a country it saw as key to the protection of its zone of influence in Francophone Africa (against the expansion of Anglophone countries allied to the United Kingdom and the United States) and a potential blueprint for relations in post-colonial Africa. President Habyarimana of Rwanda used France’s own fear, securing weapons and military training against a mythical ‘English-speaking invader’. In reality the danger Habyarimana was trying to guard against came from the Tutsi who had been forced into exile during the 1973 coup that had brought him to power. Neighbouring countries tried to broker a deal in favour of a power-sharing government, however the implementation of the Arusha Agreement signed in 1993 was cut short after the plane of President Habyarimana was shot down, sparking the 1994 genocide. The extremists were eventually rolled back by the same forces France had feared.

As for my pen-friend Victoria, she stopped writing one day. Maybe she escaped. More likely she joined the two million victims who died of violence, malaria and dysentery in the refugee camp of Goma, on the side of Lake Kivu.

There are lessons to be learnt from Rwanda. In March 2021, the French Commission of Research on the Archives Relative to Rwanda and the Genocide of Tutsi reported on the role France had played in Rwanda. The document addresses the question of France’s role and engagement in Rwanda in the run-up to the genocide and deals with French political, institutional, intellectual, but also ethical, cognitive, and moral responsibilities. It explores the almost schizophrenic way President François Mitterrand’s Government sought to encourage the democratisation of Rwanda throughout the 1990s, whilst at the same time providing the extremist government with extensive military support in response to a mythical foreign threat coming from English-speaking Uganda. France understood the risk posed by Uganda through an ethno-nationalist prism reminiscent of colonialism, projecting fears of losing a foothold on France’s area of influence in Africa. The report states that ‘this conception gradually spread through the ministries as well as the central administrations between 1990 and 1993, even if the analysis of the precise nature of the military threat posed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) varied according to the services and the advisors. In October 1990, this threat was qualified as “Ugandan-Tutsi”.’ This expression is frequent in the archives and reveals the French authorities’ ethnicist interpretation of Rwanda. This conception persisted and fuelled a way of thinking where, given the Hutu majority, the possibility of the RPF victory was always equated with an anti-democratic takeover by an ethnic minority.

The 2021 report is a rare act of reflection from France on what could be considered part of its colonial past. On France’s ethnicist reading of the situation in Rwanda, the report writes that ‘this perspective corresponded poorly to the Rwandan reality given that the country’s political and social resources were resistant to the influence of ethnicization.’ The report adds that ‘ethical responsibilities regarding political action call into serious question the decisions made at the highest level that misunderstood events even when all the information was available’, further adding that there is also a cognitive responsibility when a country fails to realise that its ethnicist reading ‘repeats a colonial pattern’.

What we should have learnt is the danger of institutions and the media propagating clichés, and labels and that when we artificially categorise people, we run the risk of dehumanising a mythical other.

It is this last warning that resonated with me the most when I read about the students in Ukraine. The implication that stared me in the face when talking with my friend Arsène, trying to find a reasonable explanation for the lack of interest the press had shown in his story. It made me question whether we have learnt anything over the past quarter century. What we should have learnt, however, is the danger of institutions and the media propagating clichés and labels, and that when we artificially categorise people, we run the risk of dehumanising a mythical other. Recently, we saw the introduction of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which creates a two-tier asylum system whereby people entering the UK via irregular means risk being criminalised and deprived of the rights defined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. Part of the same act enabled the signature of the UK‘s Migration and Economic Development Partnership with Rwanda, a programme of government-funded deportation.

As a student of history, the term deportation itself brings visions of overcrowded families held in stadiums and crammed onto goods trains. People dehumanised with labels, who we now equate with the Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war brought on them by Russia. On the one hand, we have white Europeans being compared to the victims of the Second World War and pitied for their ordeal. On the other, we have migrants from the South, seeking asylum in much more precarious circumstances, also fleeing their homeland, due to conflicts often of our own making. Yet increasingly, we are fed a dehumanising language that demonises some migrants over others, creating a hierarchy. Here, victims, our brothers and sisters. There, criminals, nameless faces, numbers flooding in. Here – there is no longer room at the inn. In the meantime, my friend Arsène still hopes one day he can go home.

As a student of history, the term deportation itself brings visions of overcrowded families held in stadiums and crammed onto goods trains. People dehumanised with labels, who we now equate with the Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war brought on them by Russia. On the one hand, we have white Europeans being compared to the victims of the Second World War and pitied for their ordeal. On the other, we have migrants from the South, seeking asylum in much more precarious circumstances, also fleeing their homeland, due to conflicts often of our own making. Yet increasingly, we are fed a dehumanising language that demonises some migrants over others, creating a hierarchy. Here, victims, our brothers and sisters. There, criminals, nameless faces, numbers flooding in. Here – there is no longer room at the inn. In the meantime, my friend Arsène still hopes one day he can go home.

This Is Not Who We Are, by Franco-Welsh author Sophie Buchaillard, is inspired by the author’s childhood correspondence with a Rwandan refugee. It is published by Seren Books (£9.99). For more information visit: www.bit.ly/ThisIsNotWhoWeAre

This article is part of our summer reads series.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.