Ambiguous and contradictory statements mean that the media’s scrutiny is more important than ever, writes Professor Stephen Cushion.

The UK government’s decision to introduce strict new measures to limit social contact comes after many people continued to ignore official advice not to mix in large groups.

The health secretary branded people “selfish” for not heeding its initial guidance. But the government’s own communication strategy should also be held responsible for failing to adequately inform the public about the actions needed to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

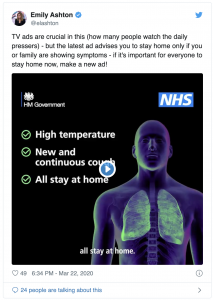

Last year the government set aside £100m for an advertising blitz about getting ready for Brexit, despite the topic being intensely debated over the previous three years. Today, there is a far stronger case for investing significantly more money into a high-profile public health campaign that will prompt immediate behavioural change.

While a limited government campaign was launched in early February – to “Catch it, Bin it, Kill it” – the messaging was clearly not stark enough to alert people about the dangers of spreading the coronavirus. More public health warnings have been produced since then, but given the government’s fast-changing official guidance, adverts have not always remained up to date.

In public speeches, media appearances and press briefings, the government’s own communication about the risks of coronavirus and the guidance people should follow has been patchy, with often evasive, ambiguous and confusing messaging.

Take, for example, the government’s daily press briefings. Just a few days ago the prime minister, Boris Johnson, was clearly not two metres away from other speakers, breaching the government’s own advice to the public. Now, with more restrictive measures in place, the importance of visually communicating the government’s guidance has been recognised.

Reporting ‘the science’

The government has consistently claimed its decision making has been in response to “the science changing” – a line echoed in many news headlines, including across BBC output.

After all, many countries implemented tougher restrictions on its citizens’ movements before the UK. In doing so, should broadcasters have broken free from a reliance on state information and led with scientific perspectives that advocated a different approach to countering the spread of the disease than the UK?

At the same time, would routinely counterbalancing the goverment’s judgements – informed by its scientific advisers – with the actions of other national governments and leading experts in fields such as epidemiology and virology add more confusion than clarity about the UK’s response?

To help people understand how the scientific evidence informs government decisions, broadcasters could more prominently feature the goverment’s own medical and health experts. For example, in one live press briefing – without the government present – they transparently explained many of the factors that the scientific advisory group for emergencies (SAGE) is grappling with when it recommends what action to take and when.

While journalists have asked the government tough questions about its response to the pandemic in press briefings, most people don’t tune in live to the daily Downing Street conferences but – as recent Ofcom research has confirmed – they rely on the framing of news media stories, such as scanning headlines about the science changing. Of course, given the unprecedented health crisis, people may be reading the news more carefully.

It doesn’t help that professional controversialists such as Daily Mail journalist Peter Oborne and Brendan O’Neill, the editor of Spiked magazine, have been ignoring much of the scientific advice, undermining government guidance and giving cover to people who still want to congregate for parties.

Responsible scrutiny

Broadcasters, by contrast, have taken a more responsible public service role, carefully informing people about the latest government advice. But, rather than just conveying government statements could they have questioned the government’s policy more robustly? After all, the public needs rigorous independent analysis of the expertise informing the government’s scientific judgements.

As news bulletins have often focused on the prime minister’s press briefings, the government’s official health guidance has not always been clear or consistent. While its previous advice had been people are still free to go to public parks, for example, it was left to Sky News reporter Sam Coates to highlight the flaw in this plan.

But while the focus of media coverage is often on the prime minister’s statements, journalists covering the pandemic – judged by the government itself as key workers – have a duty to explain whether the government’s finer judgements are justified on scientific grounds.

When there is ambiguity in the government’s approach, we need journalists prominently holding them to account. Not long after the lockdown was announced, for example, ITV’s Good Morning Britain presenter, Susanna Reid, exposed the government’s confused messaging about whether children with separated parents could move between households.

Now more than ever the government’s strategy needs to be articulated clearly and without ambiguity. But we also need journalists to continue questioning the official guidance and the scientific evidence that informs it.

This article was first published on The Conversation.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.