What’s in a name? Gareth Leaman examines the meanings embedded in toponyms and what they can and cannot tell us of a community’s history.

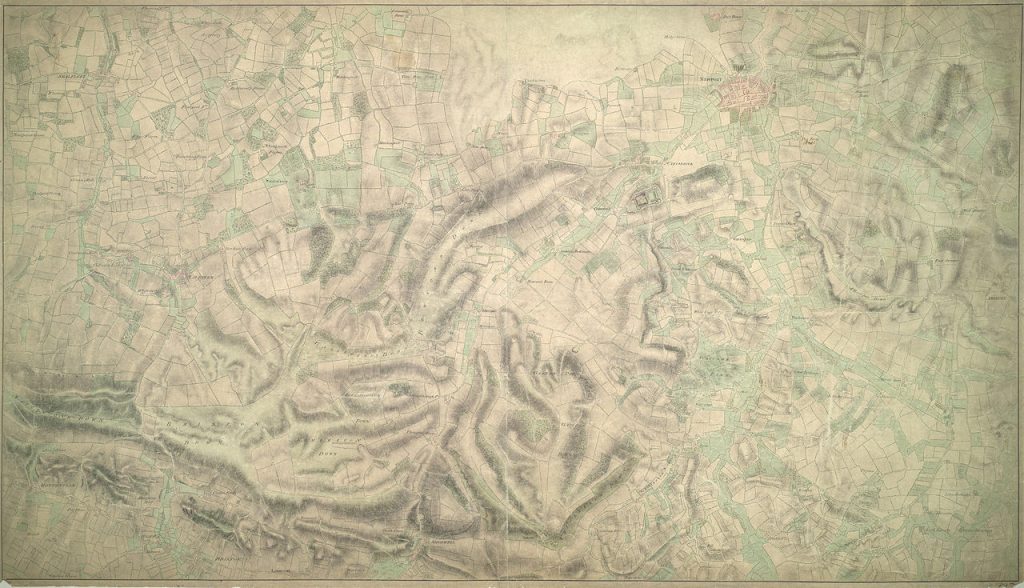

Examine any map and it becomes clear that society inscribes itself, literally, upon the landscape through the nomenclature that arises from the uses wrung out of it. The toponyms of a region contain within them much more than a mere etymology: they also form a system of signs, a web of interconnected meanings through which we can chart societal processes.

Consider how a place name may in the first instance refer to a feature of the natural landscape upon which a place is built – a river valley or a hill, say – yet it can also refer to the various ways in which its inhabitants have made use of this land over time: from farms and homesteads, to aristocratic estates, to the scars of industrialised labour and beyond.

From such observations, much can be inferred about how power has been constituted and wielded in any given epoch, and on which political terrains it has been fought for. As Rhian E Jones and Matthew Brown have identified, ‘Land use, ownership and access is fundamental to the exercise of power in the UK, and is historically tied to the country’s economic transformation.’

We can see in contemporary Gwent, for example, where the terminal decline in heavy industry – around which most inhabitants of the region would have previously lived – has given way to an endemic insecurity of employment and housing.

We can observe this acutely in the political formation of South Wales. ‘There can be no doubt’, Daryl Leeworthy notes, ‘that social democracy, as with liberalism before it, and neoliberalism after it, was written into the urban landscape’, namely through the ‘range of institutions that were instinctively of the labour movement’ which ‘served as markers of a working-class urban environment that sat alongside, and was eventually to replace, the earlier landscape put there by rulers of a different kind.’

This holds true as new social processes emerge: we can see in contemporary Gwent, for example, where the terminal decline in heavy industry – around which most inhabitants of the region would have previously lived – has given way to an endemic insecurity of employment and housing.

The consequences of this process can be felt in two related social phenomena: longstanding residents forced to travel further afield for employment, while the alleviation of housing crises in neighbouring regions has spurred many to find solace in Gwent’s relatively cheaper housing stock. These circumstances have sent the property market into overdrive, with new housing developments emerging at a dizzying rate to serve this newly-untethered polity. As a result, the social formation of contemporary Gwent is defined by the displacement of industrial communities by that totem of post-Thatcherite precarity: the commuter town.

As ever, the politics of this process – its causes and consequences – can be traced through the semantics of new and altered names of the places in which it can be observed. Many of these new developments are awkwardly tacked onto the outgrowth of existing estates, or squeezed into any patch of land that becomes available. But many more are large enough, or distinct enough from existing settlements, to necessitate the generation of a new place name altogether.

Most of these fall into two broad categories: names with a spatial connotation, and those with a temporal connotation. The spatial names exhibit an attempt to embed themselves into their surroundings by referring to local geography or a natural feature. While these are occasionally links to the local landscape that would confer a coherent meaning for those already familiar with the area, more often than not the names these developments adopt are hopelessly generic.

One of the most egregious examples is St. Mowden’s gigantic Glan Llyn estate, placed on the grave of a steelworks entering the final phase of its decades-long managed decline, and in the shadow of an Amazon distribution centre, but plainly built with the aim of accommodating white collar commuters. Yet no such toponym can be traced beyond this sprawling private space, it being wholly invented out of the ether. Even the lakes from which its name is derived are artificial, and even then they are shrinking with each round of planning application. The developer states that they ‘will provide’ these pseudo-natural features in an effort to ‘[stay] true to its natural green surroundings’, and ensure that the ‘community will evolve to reflect its wider environment’ – rather than, one might infer, organically arise from it.

Elsewhere, the toponyms with temporal significations trade in ghoulish claims to authenticity by allowing themselves to be haunted by the establishments that occupied the land before it was repurposed. The developments of this type do not denote a spatial proximity to a local landmark in order to appear as an outcropping of the natural environment, but rather a temporal proximity to a landmark that is no longer there in order to insert itself into a locale’s cultural lineage.

Typically, uses of these connotations emerge through private developers being able and willing to acquire property owned by defunded public bodies desperate for extra revenue, appropriating historic buildings and cultural institutions whose purpose has been exhausted or rendered obsolete by a politics that has no value for them.

Redrow’s Parc y Coleg typifies the eerie presence of such estates: occupying land where a university campus once stood, but now bearing little meaningful resemblance to this rich cultural heritage beyond the vague intimations of its new name (an uncanniness also evident in its brief interregnum as a filming location for a television series). Like Glan Llyn, the site is defined by its lack: ‘Parc y Coleg’ is very much not a college, its name belying the politicised creative destruction that has made its existence possible.

We can observe, then, that the key characteristic linking these developments is how necessarily abstract their chosen names are, conveying a precise level of meaninglessness that has the appearance of a coherent toponymical connection to its surroundings, but in actuality is merely masking that they have been urgently conjured from nothing in the rush to meet market demand.

Innovative. Informed. Independent.

Your support can help us make Wales better.

An examination of the difficulties each estate has had in establishing itself makes the need for such semantic obfuscation clear. Almost without exception, Gwent’s new builds have been plagued by a failure to integrate themselves into the local landscape without disrupting existing communities or damaging the natural environment. Parc y Coleg is destined to worsen Caerleon’s already ‘dangerously high’ air pollution levels, with particular concerns regarding its impact on a nearby primary school. Concerns have been raised that Glan Llyn is partially built on a flood plain. Candleston Homes’ ‘Coed Glas’ development has transformed the village of Llanfoist into ‘an unattractive urban sprawl’. The list goes on.

Meanwhile, life on the estates themselves structurally inhibits residents from forming meaningful links with their surroundings and building a strong community with their neighbours. Amenities – at least at the point of opening – are often sparse, and it is a common occurrence for once-promised services and ‘community hubs’ to be replaced with yet more housing in order to wring maximum revenue from the available land.

It is also difficult to imagine that the architecture of the houses in question does much to imbue residents with any sense that their new community may possess anything resembling a unique local character: these facsimile estates are populated by identikit houses with names and styles suggesting that they could belong anywhere in Anglophone Britain (there is ‘nothing local [in] the standard UK mock Georgian look’, as one Llanfoist resident put it).

Most pervasively, promotional materials make it clear that, for residents, their communities are fundamentally transient places, defined not by their own value as somewhere to call home but by their proximity to somewhere else, and the ease with which you can leave. All are ‘strategically located’ with ‘excellent transport links’, always ‘minutes from the M4 and within easy reach of Newport and Cardiff beyond’.

The very nature of car-powered commuter towns fates its occupants to disperse all over the wider region for work each morning, making for communities with little in common beyond the need for a driveway and a roof over their heads. Long gone are the Fordist days of whole towns being dominated by one industry, where neighbour and workmate being one and the same did much to forge the bonds of solidarity.

In an era in which private home ownership is the highest state of living, ‘homes’ are first and foremost ‘houses’: commodities to be produced and sold for profit, and purchased and owned like any other consumer good.

And with the resultant traffic chaos causing rush hour to stretch long into the evening, there is little opportunity for camaraderie with the fellow occupants of one’s cul-de-sac. It would seem that all the settlements of Gwent have become what Raymond Williams foresaw in the transformation of Glynmawr in his novel Border Country, itself a thinly veiled cipher for his own birthplace of Pandy:

‘The houses seemed now to stand in relation to the road, rather than to each other. It was no longer an enclosed village, but a place on the way to somewhere else, as almost everywhere in Britain was coming to be.’

It would seem, then, that the key signification linking these toponyms – whether spatially-derived or temporally – is the need to bind their referents in a secure sense of time and space, concealing the disruption caused by private developers while offering its displaced residents a simulation of belonging.

Try as they might, the new build estates that pockmark Gwent cannot escape their status as what Grafton Tanner (by way of Marc Augé) has described as a ‘non-place’. Such an environment, Tanner writes, ‘is not just the opposite of a place; it is the opposite of a home’:

‘Home isn’t only where you feel safe but also where you can stay, where time can slow down, where you can relax (until the time comes to leave it). Non-places, on the other hand, are in-between places; it’s hard to plant firm roots in non-places, because they incite movement.’

The names assigned to these developments, therefore, would seem to imply a desire to redress a general absence of security that all disparate prospective residents may feel.

We should note at this juncture that such a phenomenon is only possible in the sense that the marketisation of housing has allowed for the possibility of stability to become a precious (and for many a rarefied) commodity. In an era in which private home ownership is the highest state of living, ‘homes’ are first and foremost ‘houses’: commodities to be produced and sold for profit, and purchased and owned like any other consumer good.

It is little wonder then that developers sell the virtues of their properties as being a haven from the instabilities endemic in modern life, despite being responsible for the reproduction of such conditions in the first place. The cultural logic of the new build housing estate, therefore, is the commodification of a yearning to be absolved of placelessness, and it is this feeling that their names primarily connote.

This yearning is essentially a form of nostalgia: an emotion which, it is crucial to note, has both a temporal and a spatial dimension. As Tanner writes, ‘so many have been displaced by capital; they roam in search of homes and lost time’, and thus the appeal of non-places is their function as ‘nostalgia-scapes’, which are ‘artificial locations that are meant to anchor people to some kind of meaning by providing them a representation of roots’.

Thus in a time of enforced insecurity of working and living, and in a culture in which the uncertainties of mass deindustrialisation looms large, the non-place offers a mirage of a meaningful link to the past and the land: a small sense of permanence among the insecurities of life. It is this desire that new build developments are reifying and exploiting, providing the treatment for a malady that they themselves reproduce.

If, as stated, all marks on the landscape are reflective of the social processes of power and domination that have produced them, then there are no ‘authentic’ places – or toponyms – to which we should return.

That is not to say, however, that the possibility of forming true communities within these locales – and of rewiring the social structures that give rise to them – is totally precluded. Indeed, the very notions of spatial and temporal belonging can only be invoked in the projected aesthetic of these spaces because they derive from values and emotions which people genuinely feel and, crucially, hold in common. Were this desire not present, it wouldn’t be such an alluring means by which its satiation could be commodified and exploited by profit-driven developers.

The semantic games observed here reveal that the fight for ownership of land between capital and the collective remains a central site of political struggle. And so if meaningful communities do eventually form in these non-places, ones that live out the true essence of solidarity only superficially signified by this emergent toponymic phenomenon, it will be achieved in spite of the forces that seek to assert a claim to the cultural commons while demarcating it as a private space.

The uncanny connotations of their names reveal the visions of community offered by the new build commuter estate to be a simulacra – a copy without an original. Rather than conceptualising these places as clumsily falling short of some idealised authenticity, it should instead be considered that there is no authentic version of such places to begin with. In attempting to push beyond the superficial invocation of the non-place, we should recognise that the spatial and temporal absolution it offers either never existed or cannot be recovered.

If, as stated, all marks on the landscape are reflective of the social processes of power and domination that have produced them, then there are no ‘authentic’ places – or toponyms – to which we should return. By extension, whether it’s the individuation that defines (post-)neoliberal working life, the mass labour exploitation the industrial age, or further back in time still, the processes that drive the measures seen in all epochs, and bound up in the connotations of place, are the same: capital accumulation, private acquisition of wealth and power at the expense of the commons, and so forth. Only the modes of production – and the resultant aesthetic – have altered.

Robust debate and agenda-setting research.

Support Wales’ leading independent think tank.

If the holders of power have remained in similar hands across the decades, then so too has the virtues of redressing the imbalance. Williams writes evocatively of the ‘bitter and brutal struggles’ that formed the ‘intense sense of a community’ throughout South Wales, establishing ‘new notions of mutuality and brotherhood’, within which could be found the possibility of ‘a political movement which should be the establishment of higher relations of this kind and which would be the total relations of a society.’

This is what was of value in the old industrial communities and landscape of South Wales, and not the mere fact of their existence. Nor is the value to be found purely in the aesthetic by-products of such a way of life that are often mined for present-day political inspiration, and which is in many ways the ‘authentic’ standard that these new build estates are attempting to fill the emotional void of. The desire for a ‘return’ to this is not a temporal dimension, or even a spatial one, but a political one.

To truly politicise such desires, then, it is incumbent on fledgling communities to convert these latent kernels of solidarity into a coherent means of restructuring their neighbourhoods into more edifying ways of living, which can then in turn form powerful sites of resistance against the political forces that gave rise to them.

At the core of all discussed here is the matter of ownership: residents have no meaningful way of building community infrastructure: it is either imposed by developers as a means of placating local councils, or does not exist at all. And at the level of governance, as it stands there is little means of taking political control to seize or build community assets where none are granted by profit-driven owners of the land on which they sit.

To combat this, it is essential to reassert, as Jones and Brown write, ‘the belief that ordinary individuals and groups are capable of taking ownership, direction, and control of their own resources in order to improve their own lives.’ Were this to happen, we might one day analyse the toponyms of the landscape and find that while the signifiers remain the same, they instead now connote the process through which people truly took control of the commons for themselves.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.