Dylan Moore enjoys A470: Poems for the Road, a bilingual poem collection taking inspiration from the road crossing Wales from North to South.

This fully bilingual anthology of 51 new poems is the latest addition to a lineage of cultural endeavours that cherish the myth of Wales’ longest A-road. There was a multi-artist photographic exhibition at Oriel Mostyn in 2001, and more recently by Glenn Edwards’ Route 47Zero. In 2014, BBC Radio 4 produced a documentary fronted by Cerys Matthews, packaged for a UK audience as ‘The Welsh M1’. That was after an S4C drama series, a song by Geraint Lovgreen and a football fanzine. Academi, forerunner of Literature Wales, also named its magazine A470.

The A470, described by the book’s blurb as ‘186 miles from shore to shore through the backbone of Wales’ – is, of course, a myth Wales needs. Angela Graham’s poem ‘An Irishwoman is Introduced to the Major Roads of Wales’ makes the point that – in reality – the country’s real trunk roads, the A55 and the M4, are a colonial legacy. The poem’s Welshman tells its titular Irish woman ‘Wales is just a place the English cross to get to you!’ By contrast, the ‘kinking, juking road / – now right, now left, about and around’ celebrated in the collection title runs north to south, or vice versa depending on where you begin, and what Welsh and Irish have in common it seems is being ‘smaller people’, ones who ‘take the crooked route’.

A collection full of its own peaks and troughs, detours, blind corners and moments that reach for the sublime.

And this crooked old route, invented as a way of making the transport links between the north and south of Cymru seem far better than they are – strung together by renumbering parts of roads formerly known as the A438, A4073, A479, A44, A492, A489, A4084, A458, A487 and A496 – forms the spine of a collection full of its own peaks and troughs, detours, blind corners and moments that reach for the sublime.

It opens with a Cool Cymru gag from Des Mannay about Cerys Matthews and road rage, but other poets draw on much older stories: Brân the Blessed and Blodeuwedd both make appearances, while Ion Thomas makes the inevitable comparisons with Spain’s Camino de Santiago and the USA’s Route 66. It is classic Wales, indulging our national penchant for combining delusions of grandeur with self-deprecating humour.

A quick flick through the collection brings with it a slew of placenames – ‘Aberfan, Merthyr, Llanfair-ym-Muallt, Llanidloes, Dinas, Brithdir’ – each with their own resonance or lack thereof for the writers and readers alike. A470 aficionados will be delighted with appearances for the (now sadly defunct) Little Chef near the Royal Welsh Showground at Llanelwedd and slightly baffled by poems that go off-route. Sara Louise Wheeler’s ‘Conference at the Green Hotel’ recalls the pre-Zoom days when pan-Wales meetings were ‘Just as inconvenient for everyone’ – but purists will point out that for Llandrindod Wells you need the A483.

Discussions and debates that drive Wales forward.

Join Wales’ leading independent think tank.

Other places recur, criss-crossing the collection and building a sense of national community through shared experience. In Tudur Dylan Jones’ poem ‘I’r A470’ the ‘Cross Foxes’ smile’, then Eabhan Ní Shuleibháin ‘[swerves] off by the Cross Foxes and on to the mountain car park’, while in Kevin Mills’ ‘Gwydion Southbound’ the protagonist sees his fourth badger of the journey outside the same landmark pub outside Dolgellau, where the ‘470 intersects with its sister road, the A487 west Wales highway.

Some poets focus on singular places along the route. Mererid Hopwood writes her poem ‘I Ferthyr’, Stephen Payne pokes around ‘Pontypridd Museum’ and in ‘Interweaving’ Christina Thatcher’s epiphany arrives ‘on the bus from Pontypridd to Cardiff’. Others attempt to envision the whole 186 mile route in a unifying conceit. Adele Evershed’s ‘The Art of Embroidering a Road Through the Eye of Heaven’ uses an experimental format to bombard the reader with images of needlework: ‘a delicate scarlet cross-stitch / over Rhos Goch’, ‘button holing through Builth Wells’ toward ‘the bullion knots of Cardiff’ and ‘rough purl Caroline Street / chips and curry sauce / banging’. Likewise ‘Unzipping Wales’ by Ben Ray urges the reader to ‘Grip Wales firmly by North Shore Parade at Llandudno / and pull downwards’. It’s a neat conceit that allows Blaenau Ffestiniog to ‘[fizzle] out like a firefly’ and Cadair Idris to ‘[deflate] into the rumpled cloth of Snowdonia’, while ‘the Brecons [sic] curl back like paper when released.’

The poems talk to each other from recto to verso in what becomes a dialogue between languages

But it isn’t all geography. There are some successful personal pieces too: Rae Howells’ ‘Pipistrelle’ is addressed to her unborn child ‘before I knew you… in the dark of my body’s roost’ as ‘the afternoon’s terrible heat / grated the pavement’; Rhiannon Oliver remembers backseat childhood squabbles in ‘Dad’, while Conway Emmett reflects that ‘places others shun are Safer’ to ‘be Queer’ in ‘The Crem’ at Glyntaff.

Some of the places mentioned seem only to exist, as they do on journeys, as place names on signs; others, of course, mean everything, including home. And it is here that the editors’ decision to fully bilingualise the collection is most revealing: Haf Llewelyn’s ‘Ar y Ffordd Adra’ is called, in English, simply, ‘Home’ (and the degree to which the reader understands the difference depends very largely on where they are on the continuum of Cymraeg fluency).

The poems talk to each other from recto to verso in what becomes a dialogue between languages – like two friends trying to have a conversation across a busy A-road. This characteristic Wales retains – hearing and understanding our places, and each other, in half-heard, semi-understood whispers – is resonant in Seth Crook’s ‘Someone Coughs in Another Language’: the poet movingly travels through his family tree ‘to find the final Welsh speaker’.

It meets its apogee in the collection’s final verse, clare e. potter’s ‘Taith, Teithio – Iaith, Ieithio’. The verse begins in English: ‘That road with its name like a code to something’ and gradually sputters – like her ‘old Ford Cortina on Garth hill’ into Cymraeg. ‘My Welsh was a car crash in slick tarmac,’ its narrator concedes, her learning journey described as ‘hazardous’ before, for non-Welsh speaking readers, disappearing into fluency.

The poem is a vindication of the editors’ ambition – to address the dearth of poets working in both English and Welsh and the lack of translation between the languages, and on these terms A470: Poems for the Road/Cerddi’r Ffordd is a great success. But my big problem with the book is its lazy opening assertion, that ‘there are two languages in Wales’. It is time to confront this myth – that the ‘dragon has two tongues’ – and recognise that there are at least 98 languages spoken in Wales.

A volume two, including poems in Kurdish and Amharic, Arabic and Armenian, Panjabi and Somali would perhaps make the greatest addition yet to Wales’ proud poetic tradition. And just maybe we could also branch out – beyond this singular if glorious route to include all the roads of Wales.

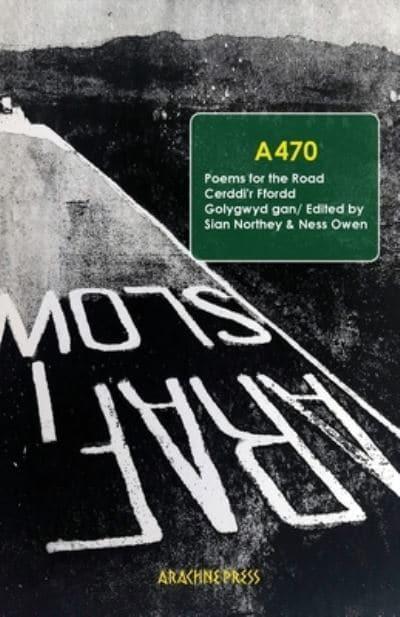

A470: Poems for the Road/Cerddi’r Ffordd

Sian Northey and Ness Owen (eds.)

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.