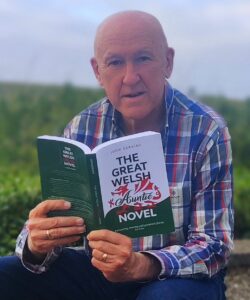

D.J. Howells enjoys an authentic evocation of 1970s Rhondda in John Geraint’s The Great Welsh Auntie Novel.

Autobiographical fiction’s desire, from David Copperfield to Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, for an authentic recreation of emotions and perceptions from the past has relied paradoxically on the retrospective shaping of memory.

Dickens’ comic absurdities, usually involving description of great metaphoric width, and Dylan Thomas’ surreal flights of fancy may cleverly entertain in their evocation of youthful scenes, but this is often accompanied by a readerly doubt about the adult writer: could it really have been like that for the child?

John Geraint’s The Great Welsh Auntie Novel inventively addresses the same dilemma in reimagining growing up in 1970s Rhondda. This is partly down to the self-confessedly heavy-handed homophonic pun in the book’s title – the Valleys’ pronunciation of ‘auntie’ being identical to ‘anti’ – which facilitates a self-reflexive latitude in giving a voice to the (often comical) promptings of the main protagonist’s inner alter ego – his ‘auntie’.

The authorial ‘sucker for nostalgia’ dives repeatedly into Welsh legends, Welsh-language sayings and idiomatic valleys’ expressions which are richly and authentically set down.

And the documentary-style commentary in the interstices of the narrative arc plays its part too, showing the workings of the fictiveness in the writing. The tale’s ‘inside-out’ structure exposing how Jac Morgan, its (anti) hero, thought and, more crucially, could not have thought makes this a kind of novelistic Pompidou Centre. Rarely can the anti-novel have had a more reliable narrator, despite its protestations to the contrary.

Taking his cue from Dannie Abse’s ‘Return to Cardiff’ where ‘the boy I was not and the man I am not’ meet, John Geraint revisits the crucible of his own identity in the Rhondda during a fateful year in Jac’s life.

Focusing on a tight group of sixth-formers at a grammar/comprehensive school the story delves into their coming to terms with their valley’s history, with their different aspirations, with their sexuality, and in Jac’s case with an unusually fervent evangelical-chapel background. This ‘transformational grammar’ (a witty nod to Chomsky) has newly amalgamated the old boys’ and girls’ schools with the co-educational experience offering new perspectives and opportunities, particularly in the form of a school production of Twelfth Night.

The cast’s chemistry as they experiment with performance and improvisation is ‘a metaphor for an ideal society, where the from each and the to each is in perfect balance’ – its Marxist proverbial ellipsis apposite to a novel which regularly dwells on the historical struggles of the working-class where heavy-industry is in decline. Their adventures are rendered with antic brio, with one particular laugh-out-loud set-piece involving a fight scene. And while the internal action homes in on Jac’s yearnings, both romantic and towards an idealistic space where friendship can impart a key to how to live, it is the Shakespearean play’s stand-out performer, Martyn, whose doomed star provides one of the tale’s most absorbing storylines.

Innovative. Informed. Independent.

Your support can help us make Wales better.

The elegiac strain evident in Martyn’s living out the Proustian quote ‘les vrais paradis sont les paradis qu’on a perdus’ is echoed in other (particularly historical) preoccupations in the novel: there is a longing for a mythical Rhondda past of The Miners’ Next Step, where the political furnace produced a vibrant culture of miners’ libraries, working-class choirs and orchestras, as well as a longing for a dazzling, thwarted future of a skyscraper-dominated (Manhattan-style), cafe-, concert-hall- and gallery-thronged valley where the wealth generated by coal has stayed there.

The authorial ‘sucker for nostalgia’ dives repeatedly into Welsh legends, Welsh-language sayings and idiomatic valleys’ expressions which are richly and authentically set down. And these notes of elegy are sharpened by what we all know came to communities like these in the first half of the 1980s. But, as might be expected in an anti-novel, this ‘unhealthy obsession with hiraeth’ is humorously deflated.

In a ‘magical Rhonddaist’ classroom sequence involving some famous figures from the past the question posed is does history teach us that Wales has no future, to which a wag responds: ‘Well, if Wales has no future, it’s got one hell of a past.’ Gwyn Alf Williams once contended that ‘there is no historical necessity for Wales… Wales will not exist unless the Welsh want it.’ John Geraint most certainly wants the Rhondda to continue to exist and in making his own version of it has, to an extent, ensured that it does.

Although there’s unquestionably a romanticising of people and place, the touchingly literal chapters charting the novel’s construction – which, like the voices of auntie, are italicised throughout – show a wryly self-aware authorial inclination to such fantasising. The self-parodying first-person refrain of ‘it’s not all about me’, too, undercuts the impulse towards self-obsession, while the many humorous passages leaven its seriousness.

As a Rhondda production befitting the home of the famous soft-drinks company, Corona, there’s definitely ‘a drop of pop on the top’; it’s a story with comedic fizz. And like other Rhondda literary productions – from those of Rhys Davies to those of Rachel Tresize – this novel defines itself on its own terms. John Geraint’s autobiographical remodelling of valleys life in the 1970s is a stirringly faithful reconstruction of what it was like to be young at that time.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.