Kaja Brown explores the work of internationally known queer artist Claude Cahun, which is currently exhibited in Penarth.

Looking around the Claude Cahun exhibit in The Turner House, Penarth, is like watching a theatrical performance unfold. Claude poses in contrasting costumes that range from the surreal to the simple to not wearing anything at all. As I look at one photo in particular that reminds me of a 1980s shot of David Bowie, I think it is clear that Claude was far ahead of her time.

Claude Cahun was born in France in 1894 to a Jewish family of writers and artists. She spent her formative years exploring gender and sexuality and chose the gender neutral name ‘Claude’ for herself. She described her gender as fluid (although she used she/her pronouns to refer to herself) and settled with a female life partner, Marcel Moore.

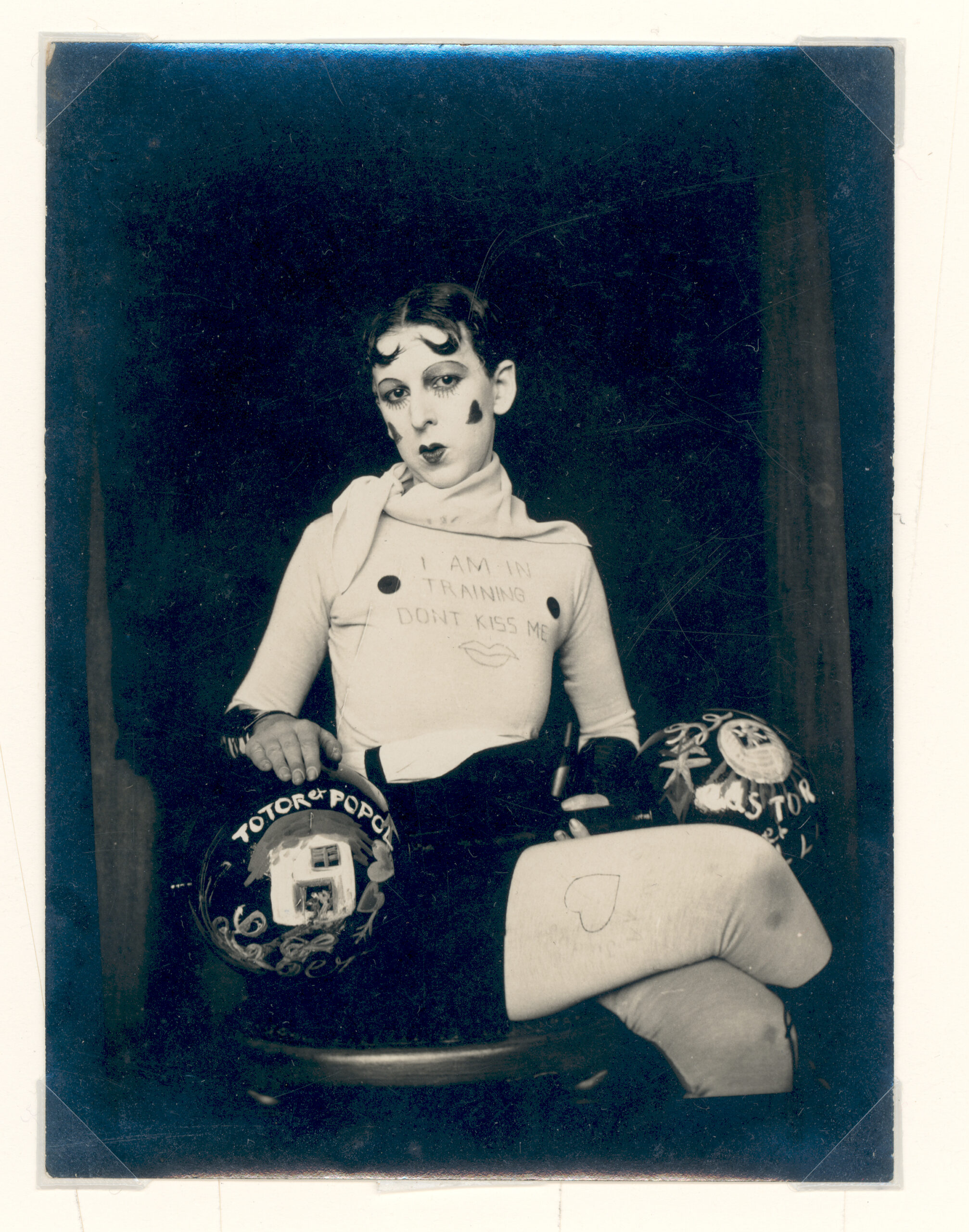

I am in training, don’t kiss me, 1927 is a particularly famous example of Claude playing with both masculine and feminine gender presentation.

Claude experimented with many art forms but is internationally known for her staged self-portraiture. Her famous photography touches on surrealism, a movement she engaged with; however she did not fully identify with it as she did not want to limit herself to one art style. In 1937, Claude and Marcel settled in Jersey which fell under Nazi occupation during WW2. Claude and Marcel became resistance activists and created a lot of anti-nazi propaganda. In 1944 they were arrested and sentenced to death, however the execution was never carried out. Claude died ten years later due to health complications she sustained while in prison.

It is exciting to see the photography of such an incredible person presented in Penarth. This Hayward Touring exhibition is in collaboration with Jersey Heritage and was first presented at the Women of the World Festival 2015, Southbank Centre. The Turner House has been a centre for arts and culture since its conception in 1881. It is a beautiful space consisting of two floors of light and airy halls. The top floor has an alcove of bookshelves and a bench to sit at, a lovely space to enjoy the work of Claude Cahun.

Each photo draws you in and tempts you to lose track of time as you attempt to dissect all the layers. You are given a tantalising glimpse into the mind of someone exploring themes of gender, performance, sexuality and self identity.

Numerous photos stand out to me. Early on in the exhibit you are faced by one photo, Untitled C.1947, where Claude is dressed in masculine clothing, taking a wide legged stance, with a cat sitting between their feet. She looks cocky and daring and unashamedly queer. Gravestones loom behind her, and a small skull is placed on the floor in front. There are also many plants, trees and bushes framing her, creating a cacophony of textures. The juxtapositions between life and death, the vacant skull and the virility of Claude, the human being and the (feline) beast, all combine to create a stunning example of the complexities of life. Claude’s photography is a work of contrasts and contradictions that represent the many facets of her own personality.

Discussions and debates that drive Wales forward.

Join Wales’ leading independent think tank.

In some photos Claude looks like a caricature of femininity, such as in Untitled 1938 where she dresses in a folk dress with exaggerated straw braids extending out of her headdress and her hands placed on her hips. In another photo, Untitled 1928, Claude looks unnervingly like a doll that has been posed. Her face is covered by a clear mask and her black cape is adorned with many other masks too. This image pertains to the performance of girlhood that was expected of women of the time and the many masks a woman would have to wear: virgin, wife, mother, daughter, sister, cook, cleaner, etc. The image feels sinister, perhaps a reflection of Claude’s own feelings around not wanting to be placed in a single box.

The image is suggestive of the expectations weighing on women in the nuclear family of the first half of the twentieth century, which Claude declined to meet.

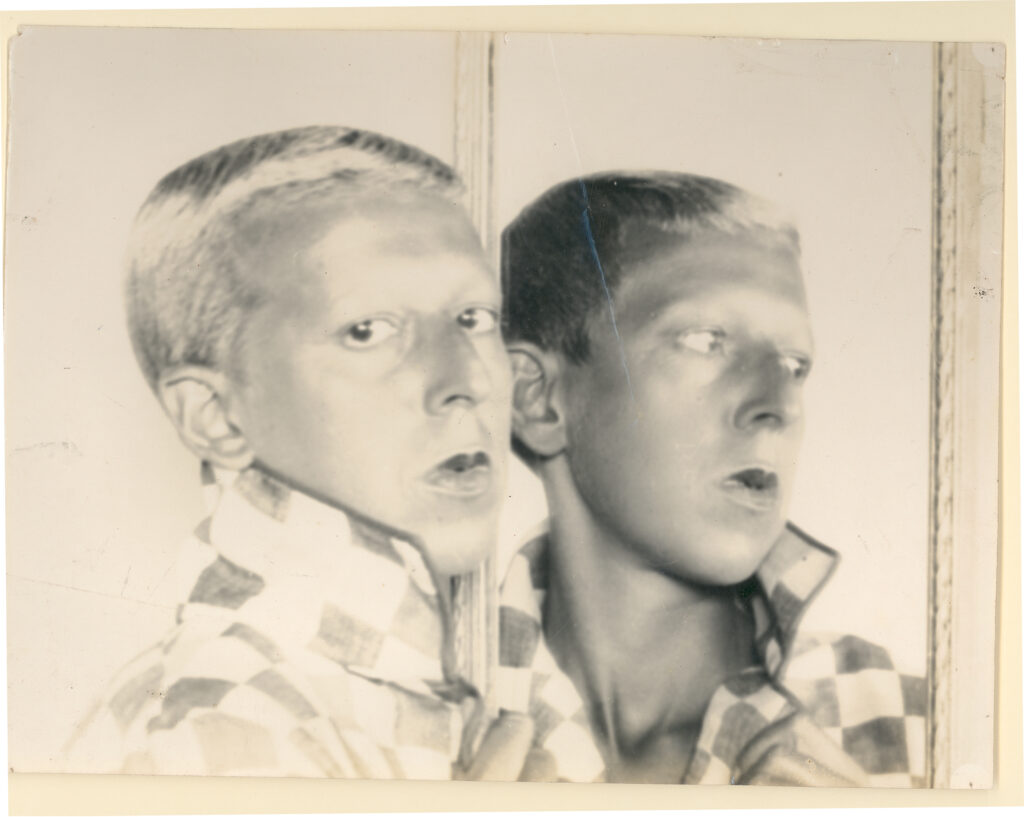

Other photos position Claude as extremely masculine, such as Untitled 1927. The photo is overexposed so that her form is blanched white and nearly devoid of curves, with exaggerated nipples. She looks very androgynous and reminiscent of male performers of the time (such as Charles Chaplin or Harold Lloyd).

I am in training, don’t kiss me, 1927 is a particularly famous example of Claude playing with both masculine and feminine gender presentation. Her hair and make-up is in the typical style of 1920s flapper women. Her cheeks are adorned with hearts, and her top has a message written on it beside circular nipples, proclaiming: ‘I am in training don’t kiss me.’ She has dumbbells resting on her lap so that the large balls of the weights sit on either side of her lap. This, combined with the white wrinkled scarf that looks oddly like a foreskin on her erect body, gives her a distinctly phallic look. The portrayal is an abstraction of gender performance with elements of feminine and masculine attributes apparently thrusted upon her form at random.

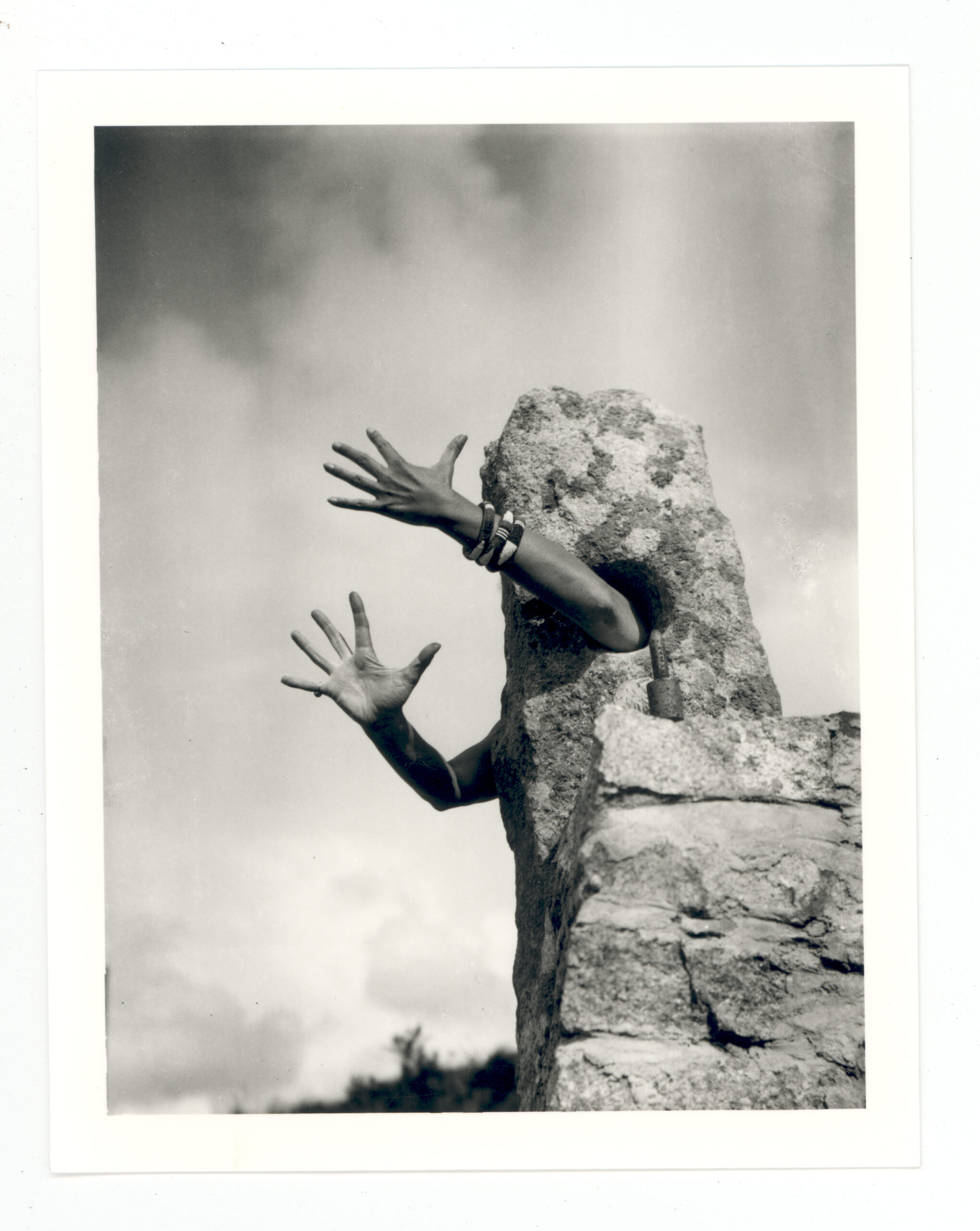

Not all of the photos focus on Claude’s form though. Several photos, such as La Chevelure 1936, focus on the image of a hand. Fragmentation of the female body was not uncommon in surrealism. In Je tends les bras 1932, the images portray arms stretching out of rock. The fingers appear webbed, with tendons straining against the skin so that the human feature appears as inhuman as possible. The hands seem to embody the connectedness of humanity, and the way we reach out to others through touch. There is something lonely about the images though. Untitled 1939 portrays two hands that appear fake: one large masculine hand cupping a small child’s hand. The only one that looks real is a feminine hand reaching out towards the other two. Although from the point of view of the camera they look like they are merging, from the shadows you can tell that the feminine hand does not quite manage to reach the others. The image is suggestive of the expectations weighing on women in the nuclear family of the first half of the twentieth century, which Claude declined to meet.

Claude’s work challenges society’s ideals, the role of women, and distorts the expectations of the onlooker. They are layered, multifaceted, and give unique insight to the mind of an incredible person who had many identities and did many great things in their lifetime. The exhibit will continue in The Turner House in Penarth until April 2 and is certainly well worth a look.

This review was written by Kaja Brown thanks to the Books Council of Wales’ New Audiences Fund.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.