Paul O’Leary discusses competitive interpretations of how we frame understandings of our history

We have just entered a period of troublesome centenary commemorations. Forthcoming events include: the outbreak of World War I (1914), the Easter Rising in Ireland (1916), the Russian revolution (1917), race riots in Cardiff and elsewhere around the Atlantic (1919), and the Irish war of independence (1919-22). In different ways each raise questions about the relationship of the past with the present and how the state, communities and individuals cultivate historical memories.

None make for easy or unproblematic commemoration. All raise the thorny question about who does the remembering and for what purpose. Are the events, memorials and publications accompanying these centenaries no more than token nods to a neutral and agreed past? Or do they provide opportunities for a more meaningful exploration of their moral and political ramifications?

|

The politics of commemoration

Tomorrow: Paul O’Leary reflects on how anniversaries are being used to promote British integration and disintegration in 2014.

|

Commemoration is particularly problematic when it comes to marking the centenary of armed conflict, as will be the case when the centenary of the outbreak of war in August 1914 will be officially remembered, commemorated and – in some quarters, it seems – celebrated as an event of conspicuous national success for the United Kingdom.

Michael Gove’s recent attacks on ‘left-wing academics’ for what he believes are their unpatriotic interpretations of the war have upped the ante. He wants a celebration of the defeat of German militarism that he erroneously believes to have been fascist. Equally erroneously, he thinks that British soldiers fought the war in defence of liberal democracy. In fact, Germany had full manhood suffrage in 1914, whereas the UK didn’t. Moreover, at the outbreak of the war the UK was allied with autocratic Russia.

Gove’s ill-tempered exchanges with Tristram Hunt (Labour politician and historian), together with robust newspaper articles by academic historians Margaret Macmillan and Richard J. Evans pointing out the tendentious nature of Gove’s interpretation, have underlined how difficult it will be to reassert a sense of common purpose and non-partisan commemoration during the coming year. With a hint of exasperation, Margaret Macmillan wrote, “Let us respect the dead, who are so frequently summoned into the debates, by trying to understand what happened, and not use them to score cheap points.” We shall see whether Gove and his allies listen.

As this episode demonstrates, it is when politicians and the state get involved with commemoration that the clash of past and present becomes most jarring. And there is much up for grabs.

In a period of economic austerity, the Daily Telegraph has highlighted the perceived inadequacy of the state spending ‘only’ £50 million on official commemorations. Moreover, now that the last surviving combatants have died, there has been a clearing of the historical undergrowth so that a new cultural landscape of memory can be planted.

But what will be brought forth? Should military success or failure be the focus of commemoration, should it be the victory or the carnage? How far should we embrace civilian experience? After all, After all, this was a total war that mobilised workers and the economy, women and men, in its pursuit of victory. Some military historians and right-wing commentators want to narrow the commemorations to a triumphalist celebration of military victory at the expense of a broader understanding of the nature of the war.

The Westminster government has established a committee, chaired by newly appointed Culture Secretary Sajid Jahiv, to plan ceremonies and events. Reportedly there have been disagreements about the appropriate emphases in the proposed official commemoration, with some wishing to play up the British victory while others prefer a more reflective attitude that allows for a proper historical understanding of the event.

Such official initiatives will mesh – and possibly clash – with popular perceptions of the Great War that have been shaped by productions such as Joan Littlewood’s Oh! What a Lovely War, overlaid with the more recent Blackadder satirical take on the conflict.

However, popular attitudes have begun to change. While Tony Blair’s military adventure in Iraq succeeded in mobilising the largest anti-war coalition since Vietnam, the distant and largely anonymous war in Afghanistan has re-cast popular understandings of military sacrifice. The Help for Heroes charity established a powerful public language for discussing the casualties of war, using the term ‘the fallen’ to describe those who died in combat, echoing the reverential term popularised by the First World War.

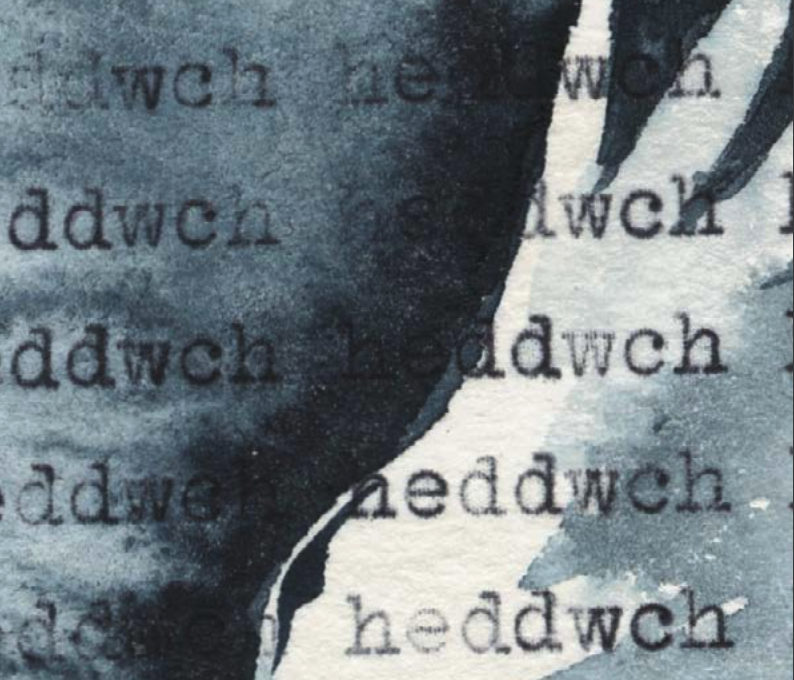

This year words like ‘sacrifice’, ‘the fallen’ and ‘heroes’ will be used extensively in the media as a way of framing public understandings of the First World War for a modern audience. The language we use in commemoration matters for how we open up or close down opportunities for asking the difficult questions about warfare in general and about the Great War in particular.

Some men and women undoubtedly did heroic and exceptional things during the war, whether that meant saving injured comrades in No Man’s Land or nursing badly injured soldiers back to health. Nobody wishes to deny those remarkable historical experiences, and they should be remembered as an essential part of a full understanding of the conflict and of how human beings respond to exceptional conditions of adversity.

But restricting commemoration to a narrative of heroism and sacrifice is selective and partial, a point frequently made by former combatants in their old age, who frequently reject the description of ‘heroes’. Furthermore, describing all combatants as heroes inhibits us from asking whether the horrific slaughter of the war was justified or justifiable.

It is sad to note that when an Aberystwyth Lecturer writes about rememberence he fails to mention David Davies M.P. 1880 – 1944 the former President of his University, who gave so generously to that establishment and the fact that his son was killed in North Africa in 1944.

@ Peter Hugh Charles Davies

Why is that relevant?

This is a very difficult topic. If Britain had retained its pre-eminent position in world politics for the duration of the 20th century, then remembering the war would have been a very simple matter: 2014 would have been a year of immense celebration, the country would have been bedecked in Union Jacks, the media would have gone bananas (with Huw Edwards in charge no doubt), and all because the Great War would have marked the apogee of Britain’s power in the world. But of course that is not the case. British superpower is now nothing more than a faint memory; a subject of immense importance for understanding how the modern world has been formed, but certainly not a topic that engenders any public pride. The heart of the matter is that it was the First World War that marked the beginning of Britain’s slide in world power, leading to the ultimate collapse of the British Empire, relegating the state to a middling position, torn between dependence on the USA and on the European Union. The Second World War recharged Britain’s imperial batteries- but only for a short while. Thus remembering the war is for the Establishment a very difficult matter. It is even more difficult for the Welsh government. Wales didn’t have a government in 1914, it didn’t even have a capital city and its national status was strictly confined to religion and culture What is even more ironical is that the very man who led Britain in the war, the man who “won the war”, was none other than that arch pacifist (he had made his name politically on the strength of his by opposition to the Boer War in 1900-1902) David Lloyd George