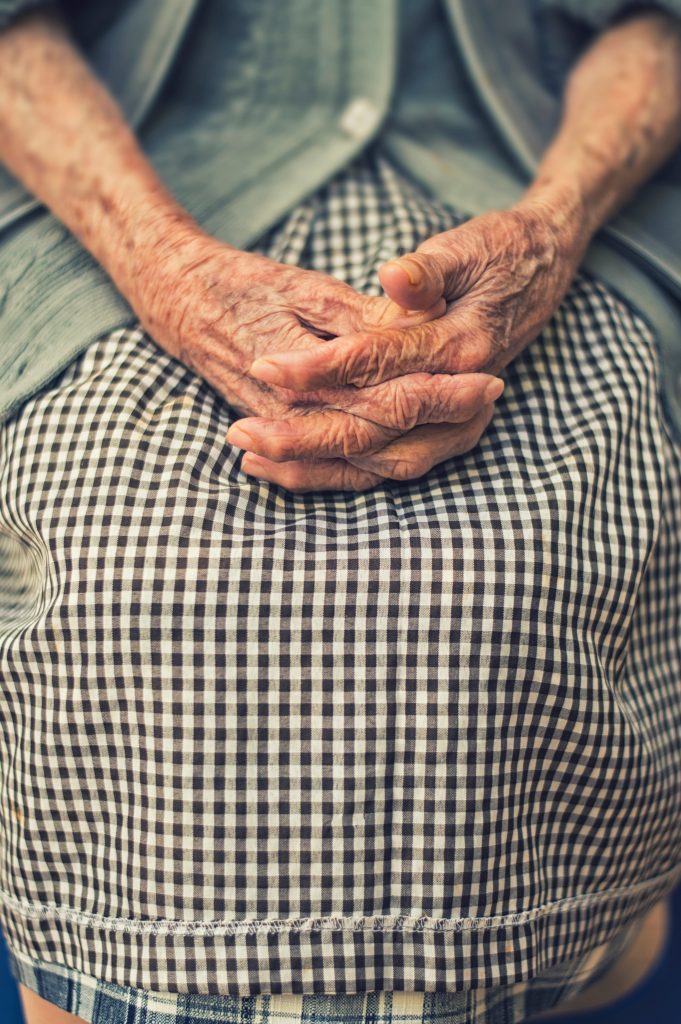

Andrew Wilson-Mouasher says that supporting community care staff is essential for ensuring people at the end of their lives receive the best care possible

Last week a report by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee revealed community nurses in Wales are leaving the profession as they feel stressed and overworked.

Every year in Wales around 32,000 people die, 75 per cent of whom will have palliative care needs. We know a significant number of these patients wish to die at home and, as the report recognises, the changing nature of healthcare means there is now a huge amount of pressure on community nursing teams.

Day-in-day-out, community care staff across the country are faced with situations many would struggle to cope with. They offer essential care and support which is often a lifeline for patients and families who are going through some of the most difficult time of their lives.

But why are they often left feeling so undervalued?

Marie Curie Nurses and Health Care Assistants care for 2,400 terminally ill people in their homes each year. Almost all of them are nearing the end of their lives, and many of them have incredibly complex needs.

It’s incredibly important that staff feel supported in their roles. At Marie Curie, we’re continually working to improve our processes and systems to allow staff to manage referrals, schedule patient care effectively and provide a better service to the people we work with. We also offer emotional support to employees across the organisation including clinical supervision, specific training and development for their role as well as access to clinical and management support 24/7.

But we know this isn’t the case for many others working in similar roles across the UK. One former community nurse quoted in the report said:

“I left district nursing after 18 years as I could not cope any longer with the stress. The job workload increased more demand on paper work and under staffed and patients could not have the care they deserved.”

Our survey with Nursing Standard, which heard from more than 5,300 nurses and care staff, also revealed similar information and found a third (33 per cent) do not feel sufficiently supported at work to manage feelings of grief and emotional stress. Half (50 per cent) also said they found accessing support systems to help them manage feelings of grief and emotional stress either difficult or they were unable to do so.

One respondent highlighted:

“There is staff welfare, but I feel that this is probably for more extreme reactions as opposed to dealing with the everyday grief and emotional stress that we experience as nurses.”

Now, more than ever, we need to make sure staff are properly supported by investing in community care so people can get the nursing care they need at the end of their lives outside of hospitals, in the place they feel most comfortable.

We know how significant an impact good care can have on patients and their family members. Looking after a loved one at the end of their lives is incredibly difficult, and being there to support them must be the priority.

Kate Harding’s father, Lambert, was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2011. In 2017 this developed into bone cancer. Lambert died peacefully in June 2018 at home, surrounded by his family.

“One of the most important things to us about the Marie Curie Nurses was the way that on each visit, they totally respected our way of caring for Dad during those last days and nights. They never spoke to us about Dad in front of him and he was always included in the conversation about his care. The Marie Curie Nurses were very kind and sensitive, showing the utmost professionalism. This calming and warm approach is something we will always remember.

“When you have these kind of people around you at such a challenging and emotional time it is so invaluable to know that you can ask questions and seek advice from those who have expertise, experience and empathy in this situation.”

Kate’s experience demonstrates the difference that good and consistent care can make to the kind of death a person is able to have. If a patient and their family’s needs and preferences are not prioritised and respected, the lasting impact on those left behind can be significantly damaging.

To achieve this kind of care we need to make sure we’re making it as easy as possible for our staff and that they have the time and resources they need, but we know too many are still relying on outdated and ineffective systems and processes. We know nurses thrive on being able to offer person-centered care but it’s important we don’t ignore the emotional impact this can have.

So what can we do to improve the picture?

In order to achieve change, we need the Welsh Government to commit to supporting those working in the community, accept the recommendations made in the report and ensure proper investment is made in community care services.

Clinical leaders need to be vigilant to the impact working with dying patients can have on care staff, and opportunities must be made for regular group debriefs. By giving staff the time and space to share their experiences and feelings we can help them build confidence in their work and a level of emotional resilience. This is particularly beneficial for those working in the community as they may often spend a significant amount of time working alone.

As healthcare professionals, the earlier we can have conversations about anticipatory care and understand what is important to the person and their family the better. We need to think about how we can equip ourselves and our teams to ensure we effectively plan and coordinate care.

In line with recommendation 1 from the report, we believe developing our nursing leaders at the front line of care and investing in quality is essential to enable nurses to deal with any fragmentation and to work collaboratively with others in the health, social care, voluntary and charity sectors.

As the report also highlights, we need to recognise the vital role community nurses play when it comes to enabling patients at the end of their life to stay at home. Without a clear picture of the ‘invisible service’, we will not be able to fully understand the palliative care needs of people in Wales and this will lead to many being unable to die at home if they want to.

At Marie Curie we believe everyone is entitled to the best possible experience at the end of their life and we wouldn’t be able to make this happen without our community nurses and care staff. As the demands on community services continue to grow we must make sure we are supporting and investing in the sector so we can be there for people at the end of their lives across Wales.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.