Duncan Fisher explores how New Zealand’s, Scotland’s and Iceland’s approach to the economy is attempting to make their citizens happier.

This is the third article in a series exploring why misery drives populism and why moving to wellbeing economics is the answer. You can read the first article here and the second article here.

In two earlier posts, I have made the case for developed country Governments who want to stay in power through democratic means, to pay more attention to wellbeing than GDP. In this article I sketch out three examples of Governments doing just this.

New Zealand

New Zealand has gone the whole hog: it has put wellbeing goals at the heart of Government. As Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern explained in Davos earlier this year, “If you are a minister and you want to spend money, you have to prove that you are going to improve intergenerational well-being… Growth alone does not lead to a great country. So it’s time to focus on those things that do.”

Finance laws are being changed so that annual budgeting is now organised around wellbeing outcomes – “actually what the public is asking for”, as Jacinda Ardern said in Davos – instead of economic inputs and outputs. The fundamental stated values pursued by the New Zealand Government are empathy, care, compassion and collaborating for the common good.

New Zealand’s Wellbeing Budget 2019 focuses on the question: how well are our people? A one-page summary at the start covers the things you might expect – productivity and the economy (with a huge part of the effort is being put into carbon reduction and sustainability) and investments in health and education. But above all those comes the things that New Zealanders are most miserable about: mental health, child wellbeing and lack of support for Māori & Pacific communities. In Davos, Jacinda Ardern was disarmingly candid about the disastrous rates of homelessness and youth suicide in New Zealand, despite positive GDP growth figures.

This is how New Zealand did it.

Step 1: Decide what measures to use

They started with OECD’s 11 current wellbeing measures introduced in the OECD Better Life Index

- Subjective wellbeing (how happy people say they feel)

- Civic engagement and governance

- Health

- Housing

- Income & consumption

- Knowledge & skills

- Safety

- Social connections

- Environment

- Jobs and earnings

- Time use

They added one for the NZ context, namely cultural identity. They also added four measures of resources to support future wellbeing – natural capital, human capital, social capital and financial/physical capital.

A huge consultation then followed to determine what specific indicators should be used to define values for these 16 measures. 500 responses, 60 submissions and innumerable discussions later, they agreed 60 indicators, set out on-line in an easy-to-comprehend format.

With these indicators, they created the “Living Standards Dashboard” – Our People, Our Future, Our Country. Living Standards Framework – Introducing the Dashboard (December 2018).

Step 2: Measure people’s wellbeing

They used measures of people’s ratings of the 60 indicators related to wellbeing derived from the New Zealand General Social Survey.

For each measure, they defined a top segment called “high wellbeing” and a bottom segment called “low wellbeing”.

Then they looked at particular population segments to see how many people featured in the high and low wellbeing segments compared to the country average. Segments related to particular family configurations (couple with children, couple without children, sole parent, and not in a family nucleus) and to the four main ethnicities (European, Māori, Pacific, Asian).

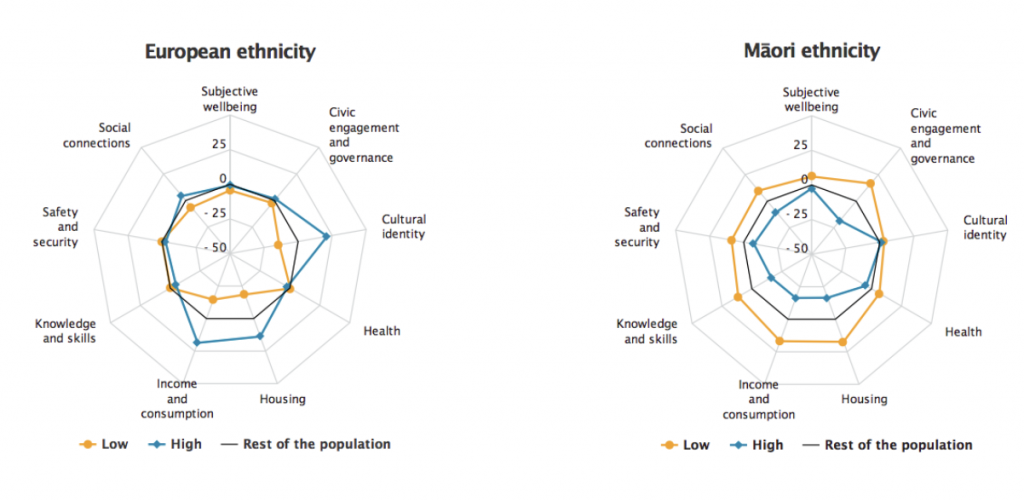

They presented this data in spider charts, giving an immediate picture of how happy these demographic groups are along a range of dimensions. Take the charts showing European and Māori ethnicities:

The blue circle shows how many more people fall in the high wellbeing category for the various dimensions than the average (represented by the black line). The further out the blue line the better, showing more people than average registering as happy. The yellow shows how many more people fall in the low wellbeing category than the average. The further out the yellow line the worse things are, showing more people than average registering as unhappy.

The charts instantly show that Māori people in NZ are considerably more likely to be less happy than those of European descent on every measure of wellbeing. No wonder that this issue found its way into the headline of the 2019 Budget.

For sure, if such an analysis had been done in UK, we would have seen Brexit coming, and where from.

Step 3: Compare NZ to other countries

Because New Zealand based its approach on measures used globally, it has included in the Dashboard a one-page overview of how the country compares globally on all 16 measures, both current and future wellbeing. This further informs the choice of wellbeing priorities, both current and future.

Step 4: Make this the basis for the budgeting

Budgeting is where New Zealand steps out in front. Measuring is good, it enables one to see at least. But reframing all Government budgeting around it is quite something else, requiring re-writing of financial law and substantial changes to budgeting processes. Every spending proposal by Government must demonstrate delivery of wellbeing outcomes. The Government is currently developing its cost benefit tools to facilitate these new computations.

Such a focus on outcomes plays havoc with Government silos. No wellbeing outcome is achievable without extensive inter-departmental cooperation. Pursuing wellbeing economics changes absolutely everything about Government. And it changes policies.

Take a proposal that the current New Zealand Government inherited – a super prison designed to bring financial value for money, a smaller cost/prisoner. But as soon as mental health and community indicators start to determine policy, the super-prison does not look such a good investment. The super prison was never built and more investment was ordered for mental health, and all based on hard metrics.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

Scotland

Scotland is making its own distinct contribution. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, in a TED Talk on the well-being economy, explained, “In the world we live in today with growing divides and inequalities, with disaffection and alienation, it is more important than ever that we ….promote a vision of society that has wellbeing not just wealth at its very heart.”

In 2018, Scotland published a new National Performance Framework. It states Scotland’s core values as kindness, dignity and compassion. The Framework defines 11 national outcomes, aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, represented in this flower diagram.

A public consultation led to cross-party consensus on a set of 81 national indicators of progress towards the national outcomes. These cover children, communities, culture, economy, entrepreneurial activity, education, environment, fair work & business, health, human rights, international and poverty.

A tool for local authorities in Scotland

The National Performance Framework includes the idea of “inclusive growth” in Government’s purpose. The Inclusive Growth Framework was developed for use by Scotland’s 32 local authorities and was piloted in 2017 in North Ayrshire. It includes a four-stage local planning process leading to action and monitoring.

Stage 1: Benchmarking against a number of other local authorities and against Scottish averages

- Economic performance (e.g. business start-up and survival rates, R&D expenditure/head, value of goods & services)

- Labour market access (e.g. unemployment/economic activity rate, job density)

- Fair work (e.g. earnings, employment in high skill/low paid sectors)

- People (e.g. health, education, life expectancy, child poverty)

- Place (e.g. internet access; satisfaction with public transport, health and schools; proximity to derelict land site, housing, sense of belonging).

Stage 2: Diagnosis

Examine the external environment, local conditions and social factors that particularly constrain inclusive growth.

Stage 3: Consultation

Find out who are considered are priority groups in the area. When done in North Ayrshire, for example, there were four priority groups – young people, those experiencing long-term health problems, those experiencing in-work poverty and women.

Stage 4: Prioritisation

Three factors go into prioritisation: (1) what things are particularly constraining inclusive growth, (2) what people in the priority groups think is most important and (3) what is deliverable given available funding and time.

Iceland

Iceland is taking steps to move to wellbeing economic measures, with action accelerating this year. The Prime Minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, set up a working group to develop measurements for wellbeing, which ran a survey on what mattered most to people. This identified four priorities:

- Good health and access to healthcare

- Good relationships: family, friends, neighbourhoods

- Secure and affordable housing

- Making a living: income and assets

The committee then produced a proposal for 39 indicators, which the Prime Minister presented at a conference in September this year. The indicators cover 13 issues: health, education, social capital, security, work-life balance, air quality/climate, land use, energy, waste/recycling, economic conditions, employment, housing and incomes. The indicators are now open to consultation and the intention is to incorporate them into Iceland’s five-year strategic financial plan, which is updated annually.

A particular contribution of Iceland to the global wellbeing agenda is its work on gender equality, which is second to none in the world. Not only is Iceland committed to advancing the role of women in work, but, unusually, the role of men in care. “We must forge ahead with progressive economic policies that defy common stereotypes about costs and benefits and keep on promoting gender equality as part of a forward-looking social justice agenda”, writes Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir in an article on wellbeing for the IMF.

International leadership: the WEGo Alliance of Governments

At the OECD World Economic Forum hosted in South Korea in 2018 New Zealand, Scotland and Iceland together launched the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo) Alliance. This highly mutually supportive group brings together small like-minded countries facing similar challenges and determined to take wellbeing to the next level.

The first “economic policy lab” was organised in Scotland in May this year, discussing such things as wellbeing budgeting, sustainable tourism and natural capital, child poverty and predictive analytics.

Should Wales ask to be part of this? Could the SIN alliance (Scotland, Iceland, NZ) become the WINS alliance (Wales, Iceland, NZ, Scotland)?

In the final of my four short posts, I venture some ideas for what next for Wales to advance the wellbeing agenda, to add to the already flourishing and creative debate.

For further discussion, Duncan Fisher can be contacted on [email protected]

Photo by Daniil Vnoutchkov on Unsplash

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.