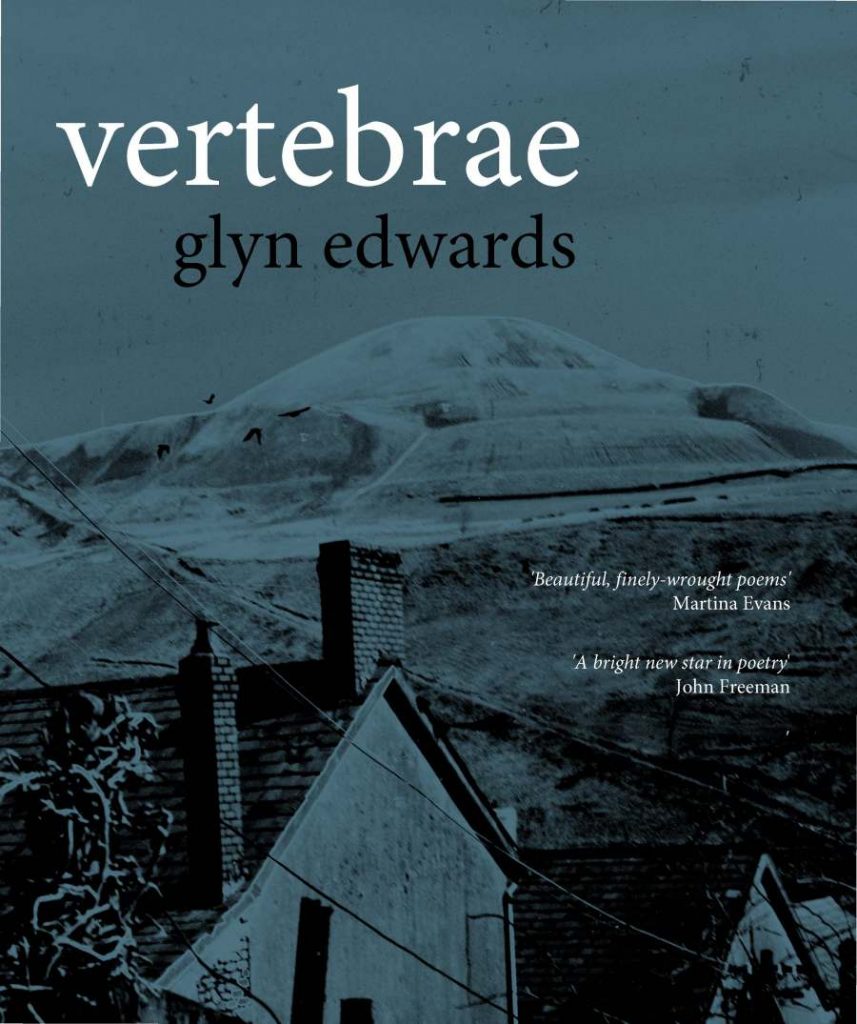

Glyn Edwards’ collection of poems that explore the potential of life, its fragility, and the ever presence of death is fascinating reading, writes Alex Hubbard

‘We’re just like Little Gods, aren’t we Dad?’

This question, posed to the narrator by his son in the poem ‘Little Gods,’ offers up Glyn Edwards’ primary theme in this collection: relativity. In ‘Little Gods,’ where a father and son collect frogspawn and later observe the dead frogs left over from the hatchings, human becomes creator and mediator, watching over its own small domain, holding the balance between life and death in its palms.

In contrast, the collection’s opening poem ‘The Land or Body Tide’ depicts the nervy process of a pregnancy ultrasound. Here, the soon-to-be father and mother are not little gods but instead are powerless as they wait to know the fate of their unborn child.

Death lingers over the poem, threatening to turn this moment tragic. Technology, too, holds a kind of Schrödingian power over the couple. Any creation of life they may have brought about is delicate, relying on the camera orbiting ‘your taciturn womb’ to uncover the state of the unborn child.

The musicality in Edwards’ poetry is self-evident, but what is particularly impressive in this poem is its tense timbre:

‘exhuming nothing but a stilled chamber’

Excavating only subterranean gloom

until the cardiograph leaps loud pulses

a backbone intones on the monitor.’

(Vertebrae, 11)

Visually, the lines are presented as vertebrae, the space between them symbolising the spine that holds them together. As the tension builds, each line ends with a staccato jolt. Their melodic quality allows each to rhythmically cross over the space to the next one, even as endings such as ‘stilled chamber’ and ‘subterranean gloom’ encourage a sense of foreboding.

In Vertebrae, each poem, each life is delicate and breakable even if as a collection it is able to withstand immense pressure and keep the body of poetic meaning intact.

Death is the ironic constant of life in these poems, often pondered over as both unnatural in its stark resolution and natural in its place as the final moment of all of our lived experiences.

In ‘A Frontal Lobe Love Poem,’ the processes of electricity and the body are linked – the narrator remembers a study where rats ‘that were clinically dead’ have their brain activity recorded by ‘EEF electrodes,’ finding:

‘evidence of thirty seconds, no less,

[where] their frontal lobe lit up and oscillated.’

From this scientific finding comes a moment of spirituality. The narrator’s partner suggests this means:

‘visions of your family, the whole Heaven fable,

is your brain reassuring you through the process.’

What does this mean? That we, the reader, and they, the narrator and their partner, should embrace and admit fully the numbing possibility that death truly is an inevitable oblivion, making our existence, our consciousness, both infinitesimal and enormous in its importance? Edwards invites these anxieties in only to firmly reject them:

‘And I don’t tell you this, and I know I should do:

When my heart stops I hope I’m lucid enough

That the remnant of my dying brain is you.’

If your reading habits are in any way like mine, your reaction will most likely be ‘crikey! A rhyme! To end a poem! Very bold!’ But subtly, Edwards throws in half-rhymes and eye-rhymes as the poem builds, so that this final full rhyme works as a lasting affirmation of love. Consider Leonard Cohen’s wonderful phrase ‘there’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.’ Here the finality of death is halted, ever so slightly undermined, with one last shout of light.

Edwards’ conversation with John Lavin, which closes the collection, is just as illuminating as the poetry itself. Edwards’ awareness not only of his own poetic lineage, primarily the influence of Ted Hughes but also of his contemporaries Max Porter and Andrew McMillan, makes for fascinating reading. But what really shines through is the insight into Edwards’ creative practice.

He discusses waking up with ink stains on pillow cases after late night ideas, reworking memories of his own son, all in an attempt to reach a particular kind of insight unique to poetry. It is an insight that, at his best, Edwards certainly succeeds in giving.

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.