Based on her experience of crisis management in conflict zones, IWA Director Auriol Miller offers thoughts on leadership when tackling society-wide uncertainty.

We find ourselves in extraordinary, eerily uncertain times, despite spring starting to beckon us outside and promise happier, warmer months ahead.

It’s been a grim, wet winter, and a particularly devastating one already for those people in Wales badly affected by the floods over recent weeks, who are facing up to the implications of homes and livelihoods devastated.

Yet this is where we find ourselves. We are, all of us, now facing up to something inherently unknown and unknowable until it happens to us, and to people we know and to those we love. We are starting to imagine a new normal and we don’t know what the future holds.

As sports and our children’s after school activities are cancelled, universities move to teaching online, Covid-19 is changing the parameters of our day to day lives, at home and at work. It will change us further in myriad ways. We are all thinking through the scenarios that we can imagine so far. There are others that we cannot imagine yet. There always are.

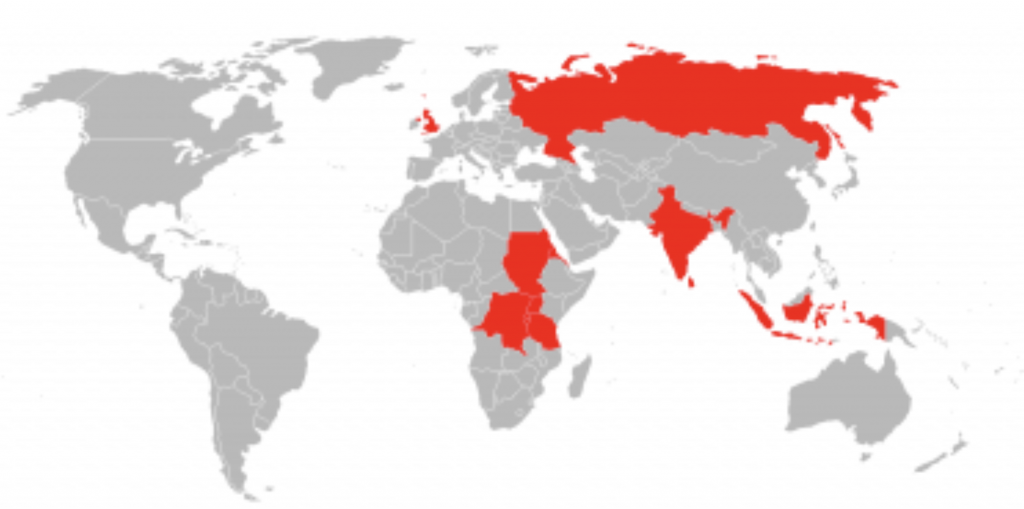

I know this from my years spent managing emergencies in humanitarian situations, working for international non-governmental organisations across the globe, and leading in-country responses in Burundi, DR Congo and Sudan.

Our role was different in different places obviously, whether delivering essential public services – clean water and sanitation, or providing nutritional programmes to the severely and acutely malnourished – as well as raising awareness of the key challenges raised and the short-, medium and longer-term policy implications of them, both for national governments and international bodies, like the UN or the EU.

Alongside this, in some places, it was possible to continue the painstaking work of building cross-sector partnerships, for instance, to build effective early-warning systems for food security for vulnerable populations, work that literally took decades to come to fruition.

Being comfortable working in uncertain times is not something that comes easily or quickly to many of us. I have lived under curfew for weeks at a time, evacuating non-essential international staff gradually while safeguarding programme delivery and the personal safety of remaining staff.

I have evacuated essential international staff in situations where non-state actors – aka ‘rebels’ – have threatened to shoot at any planes taking off or landing. I have spent nights in internal corridors, a room’s width away from an outside wall for safety, with the thud of soldiers’ boots coming down the hill on the other side of the fence and the whizz of bullets overhead.

I’ve had staff arbitrarily imprisoned and kidnapped. I’ve taken over the management of a team of 150 staff after my boss had had enough of continuing death threats against her. It was meant to be temporary, but it became permanent. I’ve had death threats myself too.

But it is one thing choosing that uncertainty for yourself, and choosing to go to work in a place that by all indicators is politically unstable or downright dangerous because of conflict between identifiable actors or between a government or coalition and those who contest their authority.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

You can at least communicate with people if the lines of communication are open, and in my old life I had the luxury of being able to choose to leave the country when it got too dangerous to continue to operate as normal. It’s quite another not to be able to make that choice precisely because it’s where you live and where your family are.

And Covid-19 is not something that has lines of communication. It is infectious, invisible and insidious. You cannot negotiate with it.

But I think that, despite this key difference, there are a few lessons that are worth sharing that may help others who find themselves in a wholly new situation, without a map or a compass or an emergency handbook to guide them. I think that they may apply, too, for parents and carers who are responsible for others, as well as for leadership teams running organisations of any kind.

Personal resilience

The first is that, as a leader, your own personal resilience matters. Your ability to identify issues that affect your organisation, to assess their potential implications, draw in evidence and canvas your team’s opinions must happen in a way that they feel included but also show that you have gripped this effectively.

All this will set the tone for everyone who looks to you for guidance. You do not need to be tough and send out an ‘I can handle this, no matter what comes at us’ kind of message. Nor do you need to have all the answers. Nobody expects you to. Nor should you expect it of yourself. None of us should. But you should expect yourself to be able to gain and hold people’s trust.

The best way to do this is to be clear about what you do know and what you don’t. People are inevitably going to be concerned about what it means for them personally and professionally. Remember to draw that distinction in your various conversations with them. Break it down into its component parts, as much as you can.

Be clear about what your next steps are, and when you are going to review things, when the next decision might be coming and when you next plan to be in touch. Keep a log of your decisions, notes on the choices you faced and the reasoning behind the judgements you made. You will need this later.

Your team matter most

Second, in whatever you are doing, your people, your team matter most.

Realise this quickly and it makes it easier to both do the job and to move between the various stages that are inevitable. There will be times for command and control, and there are definitely times to ask ‘what makes sense to you?’

Bright ideas are not welcome when the decision has already been taken so make it clear when others’ input is sought, and when it isn’t, because there simply isn’t time. Explaining yourself multiple times is an unnecessary use of resources. Think about how you are going to cascade information when everyone is dispersed and set that up now.

Use the best information you have

Third, making a swift decision based on partial information is better than dithering about what to do and thinking you can wait till you have all the facts at your fingertips. That won’t happen. You can only make the decision based on the information you have so make sure you’re using the most rigorous data and information you can.

Make sure that you’re clear when and why you are deciding to pivot to do something altogether different. Review, review, review. Your base assumptions will change as the situation changes. If you can, have someone whose role is to question these assumptions so you don’t close off avenues too soon.

It’s perfectly fine to make mistakes so long as you admit them, learn from them and don’t agonise into a downward spiral of inertia. Make sure you’re putting time into connecting with and sharing ideas with other organisations. Put aside differences and competition. How can you team up for a stronger, better response for those who need your collective, coordinated approach?

Plan ahead

Fourth, think in terms of timeframes: short-, medium- and longer-term. These will differ depending on what your organisation’s purpose is. If the period that we are in at the moment is about putting your contingency plans into action, then scenario plan and work out where the glitches are ahead of time.

If you are the glitch, and need to rest or get some perspective, then get out of the way and enable someone else to hold the reins for a while till you can pick them up again. Plan for this because everyone is going to need a break from time to time. Be clear when someone else is taking the decisions and when that period has ended.

Keep calm, keep looking forward

At the IWA, we know we’re not in the frontline of service provision and that shaping policy for the long term may not be uppermost in people’s minds at the moment. It still matters though. We also know that, despite the uncertainty, this too will pass, and that Wales and our communities and our people may be dramatically changed by what may happen over the coming months.

In some shape or form, we will all be touched by Covid-19. Yes, we should try to keep things as normal as possible as much as possible, but we should also recognise the new normal too. Changes will come whether we like it or not.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.