Rob Humphreys argues that recovery can’t all be about the economy, and that higher education will have a special role to play

Higher education is a public good. It exists to generate, disseminate and apply new knowledge and understandings for the benefit of human society and the planet.

It belongs to us all. It is an essential part of our national infrastructure. That’s my starting point – if you don’t like it, look away now!

What kind of Wales will emerge post-COVID? It will depend to some extent on how long the crisis lasts but we already hear noises off from anchor companies such as Tata and Airbus. Our economy will be bruised, fragile and probably contain greater inequalities.

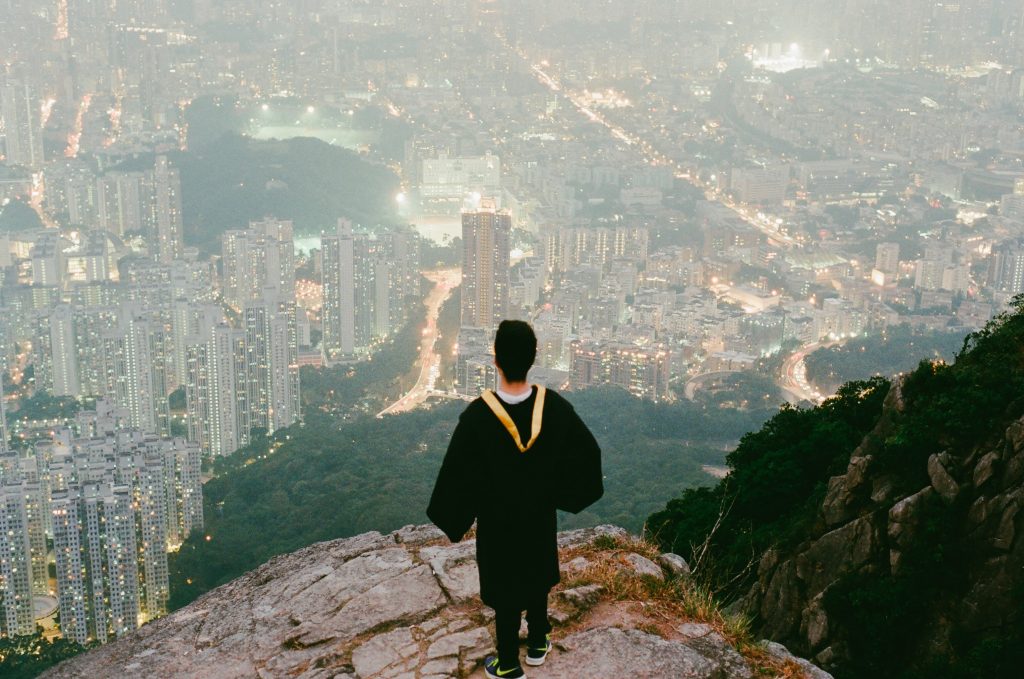

We know from Learning & Work Institute Cymru research published last week that the young, those with fewer qualifications, those in low skill/low wage employment (many of them women) will feel the immediate brunt. Spare a thought for this year’s cohort of university graduates, who may well not have even stop-gap jobs to go to, and will most likely be competing for jobs of any kind with next year’s graduates.

Much will depend on politics, and the exposed nature of the Welsh economy after Brexit should be baked into our analysis. The UK government’s overarching fiscal policy, its conception of the role and size of the state will be huge determinants. The combination of post-COVID politics and a global recession could see the emergence of the lobster state – small, weak but with a huge NHS arm.

This, and the UK Government’s industrial strategy and regional economic policy post-COVID will frame policy in Wales, whether we like it or not. As will higher education policy in England – the interwovenness is more complex than some suggest. The pressures and strains within the UK union will be a longer-term driver. We have elections to the Senedd next year – I merely observe that Welsh politics are more volatile than they have ever been in my lifetime.

Some draw encouragement from the break with the past in 1945 to establish a new social settlement. Perhaps. One might equally point to the 2008 financial crisis and how the big banks and hedge fund managers, frankly, got away with it. We should never underestimate the nature of entrenched political and economic power at UK level.

Major economic and social change will require clear-sighted visions of what is possible. Higher education should have a major role in that. If I had to bet my house, I would say that immediately post-COVID – indeed sooner than that – public debate will be dominated by the need to secure economic recovery. That may well drown out much of the other stuff. There is also a role for higher education in preventing that drowning out.

We should never underestimate the nature of entrenched political and economic power at UK level

Separating the short from the longer-term is important. Our universities face immediate financial challenges due to the loss of income from international students and a possible downturn in recruitment this autumn. Those are serious matters: it means a potential weakening of our national infrastructure. It also means a huge blow to the localities in which institutions are situated.

But if (a big ‘if’) the Welsh Government is to come to their aid, it is hard to believe that there won’t be – in the broadest terms – a ‘something for something’ agenda. The core question is likely to be: what is the ‘something’ (or ‘something different’) that our Government, on behalf of us as citizens, will ask of higher education? Or, and maybe we need to hear more of this, what is the ‘something’ that higher education will put on the table in response to the new context?

The risks are more than financial. It is salutary to note that if the ‘newly discovered’ essential workers are to be more-valued, academics are likely to find that – relatively speaking – they and their sector may be ascribed less value in the eyes of governments… and the public.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

HE in Wales has a good story to tell – not least the per capita rate of graduate start-ups, the research links with anchor companies, and the progress in recent years on integrating employability into the curriculum. But if we call for a fundamental shift in society post-COVID as many do, then it is odd to expect HE to remain unchanged.

The nexus between the private sector (including SMEs) and higher education is surely an area that needs renewed exploration. We may need a greater tolerance of risk in joint activity and joint ventures, coupled with a development bank type agency.

It is salutary to note that if the ‘newly discovered’ essential workers are to be more-valued, academics are likely to find that – relatively speaking – they and their sector may be ascribed less value in the eyes of governments…

Bringing HE more front and centre in policies that promote the foundational economy will be necessary. Similarly, the potential for enhanced local supply chains in Wales, gives universities an opportunity to contribute in terms of enhancing innovation and through their own procurement.

We need to explore the nature of ‘graduate-ness’. The wider sets of skills and attributes that derive from a university education are as important to our future as directly vocational provision. And it is a mark of a civilised society that a part of my taxes go towards research and teaching in classics, medieval history, Welsh literature, and so on.

However, higher level apprenticeships, and lifelong learning opportunities, must be brought in from the margins. The days of the standard three-year full-time degree at age 18, studied a long way from home, being the default are numbered. Following the Diamond Report funding reforms there has been an upsurge in demand for part-time study at HE level. Were the provision to be even more flexible, I believe that the demand would increase.

Someone is bound to raise the question of the right institutional fit for Wales. If there is to be reconfiguration it is best left to progress organically with some constructive nurturing from government. I see no merit in a policy of institutional crash and burn to teach the others a lesson, as appears to be mooted in England. New forms of institutional linkage between some universities and further education may well be of more value in that context, and can lead to a more productive institutional mission specialisation within HE.

Finally, at the risk of being a rather rude guest at this party, I want to challenge the singular focus on the economy when discussing higher education. Economics itself (or at least forms of economics) is a discipline that sometimes sees little need to accommodate other methods of enquiry.

Almost every academic discipline, in addition to the medical and health sciences, is relevant to rethinking and rebuilding our society after the present crisis. To cite just a few – education, social psychology, big data computing, philosophy, environmental science, engineering, sociology, history, politics, urban planning, business and management.

But, dare I say it, HE needs to show more bite here. Advocacy for HE from within HE, often drifts towards inputs – public funding, student fees and so on, rather than outcomes. It is sometimes defensive. We arguably haven’t had a public debate on the role and purpose of HE since the Haldane Commission on the University of Wales around a century ago.

The present Education Minister has rightly placed great emphasis on the civic mission of universities. Despite good work in this area carried out by all our universities, more can be done. The cultural fissures in society laid bare (not caused) by the Brexit debate are evidence of the distance that exists between graduates and non-graduates. Civic mission should be more than a project with a voluntary group here, or keeping a theatre afloat there. It is about creating and promoting a democratic impulse to do with public knowledge.

Civic mission should be more than a project with a voluntary group here, or keeping a theatre afloat there. It is about creating and promoting a democratic impulse to do with public knowledge

The production of new knowledge and understanding that we all invest in should in the end be more than trickle-down knowledge. It needs to be proactively taken outside of the walls of the academy in a systematic manner through adult education and contributions to public debate. HE is internationalist and it must remain so. But it should also serve our own communities, our own democracy. For me, the overarching framework and disposition should be one of ‘rooted cosmopolitanism’.

If we are to ‘rethink Wales’, a discussion about the economy is vital. But it is not sufficient. In the same way the exploration of an enhanced role for higher education in the economic sphere is necessary and vital – but insufficient, in capturing the proper roles of universities in Wales, and the world, post-COVID.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.