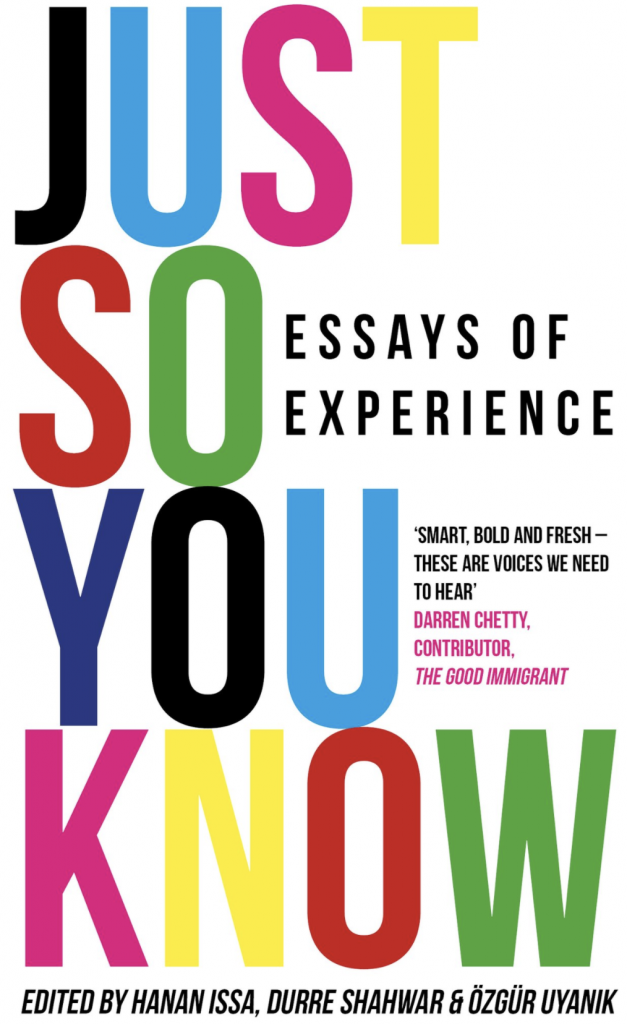

Cath Beard reviews a collection of essays on identity edited by Hanan Issa, Durre Shahwar and Özgür Uyanik.

What is a margin? ‘I, Invisible Immigrant’ by Derwen Morfayel poses this very question.

Observing ‘at its worst, it is empty space, and, and its best, it is the frame of the text’ we are given the poles of how lived experience is received in contemporary spaces. At its worst, it is absent. Decisions are made and imposed upon groups of people and onto places that are hollowed of their humanity. Cofiwch Dryweryn.

At its best, it is the central beating heart, that ‘force that through the green fuse drives the flower’. Rooted in the civil rights era is a principled and value driven idea of lived experience, of co-production, that is vital to a cohesive and responsive society. It is the frame of the text. So the opening essay sets the tone for this challenging, beautiful, timely collection.

Don’t be fooled by the book’s slim appearance for there is an astonishing breadth of experience within. The reader is invited to bear witness and to meet the authors where they are.

Brought out from the empty spaces and into the frame are experiences hard to vocalise and sometimes discomforting to read. Josh Weeks in ‘Dear O’ provides an intimate and unsettlingly brilliant portrayal of the realities of living with obsessive compulsive disorder, using the form of several letters written to the condition.

“My initial reaction was a desire to ‘police’ the language within, to make myself more comfortable.”

Dafydd Rees’s ‘Bipolar Disorder’ brings us onto an acute inpatient ward, exploring the moral questions around restraint and forced treatment through the fairytale of Rhwngdaubegwn. These are conversations widespread within the lived experience mental health community, but part of that absent space outside of it. This essay should be required reading for all within the mental health profession.

Kate Cleaver’s ‘Look At Me’ provides one of the most affecting essays in the anthology. My initial reaction was a desire to ‘police’ the language within, to make myself more comfortable. That is the beauty of this collection. It is not an easy read. Kate’s reclamation of self and the journey to her trike will stay with me for a long time.

Bodies of water are a recurrent theme across essays of startling difference. Kandace Siobhan Walker in ‘Everything I Will Give You’ weaves New York, Kenya and Myddfai together in a cautionary tale of love and power, with transformative waters and a woman’s emergence breaks both surface and with expectation.

Grug Muse in ‘Language as Water’ invokes bridge and border, dilution, sustenance and threat. The many ways water can be diverted and controlled is considered next to an exploration of Y Dydd Olaf, a 1976 dystopian novel where (without ruining anything for you) a language’s obscurity can become its strength. The visit of Grug to Tryweryn reservoir is told in brief but devastating beauty.

Sarah Younan in ‘Mzungu’ writes from perspectives rooted in the other. The child called mzungu (white person) in Nakuru, not German enough for the Nairobi ex-pat community, recognising privilege and experience weaponised in white womanhood through Sabina and her Maasai husband.

“To preserve the authenticity of voice alongside the uniqueness of each author is proof of commitment to the principles of lived experience.”

‘A Reluctant Self’ sees Ranjit Saimbi exploring the notion of belonging, through an examination of the role cultural expectations play in the construction of the self.

In ‘The Other Side’ Ruqaya Izzidien powerfully recounts an act of resistance performed at age sixteen, both against an unjust war and expectations of ‘culture’. Here, writing words onto skin and refusing to follow the rules pushes both her physical self and her identity from the margins and into the centre of the room.

‘My Other(ed) Self’ from Özgür Uyanik takes us to a Turkish bookshop, arms full of the works quoted by a Father now lost. The essay places a spotlight not only on the tensions that have brought the author to seek a relationship with Turkish literature, but also those tensions inherent in seeking ‘diverse’ voices, BAME voices, to create collections like Just So You Know.

Nasia Sarwar-Skuse considers home in ‘Belonging’, writing to ‘excavate the places which are buried within’. An essay examining identity, the diasporic experience and the power of creating ‘home’ through creative practice.

Bethan Jones-Arthur goes home in ‘Crisp’, and brings us to the bosom of maternal love and acceptance.

‘Safe Histories’, Dylan Huws, takes us through lived histories. The 1990s, Gay Pride, AIDS and the End of History meet us here, now, with battles won and still to fight. The fast-evolving horrors of the current year, only half lived, gently knock at the door as this essay is read.

When it comes to ‘Finding Voice’, Taylor Edmonds looks at the intersecting of identity, and the role poetry has played in understanding this intersection. The public acts of identity we engage in – such as which box to tick for ethnicity, for sexuality – are given form in poetry, in responding to hate crime. Identity is owned.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

Isabel Adonis has a warning in ‘Colonial Thinking, Education, Politics, Language and Race… From the Personal to the Political’. Noting the splits along linguistic lines in Welsh cultural discourse, there is a feeling of becoming ‘other’, not being Welsh enough. ‘The we no longer meant me’. Wales contains a duality – both colonised and coloniser – and Isabel rejects the outsider label, saying ‘Yr wyf gartref’.

Then there is ‘What is boccia? Don’t ask me, I just play it’, a wonderful manifesto for living from Ricky Stevenson.

Just So You Know (Parthian Books) is a desperately needed intervention if Wales and Welshness is to be truly shaped by the experiences contained within it. The act of coproducing is a necessarily uncomfortable one, and these essays challenge as much as they affirm.

Just as gemstones are formed under great pressure, growing in value and beauty as a result, so this collection offers experience in all its sharp edges and striations, the polish or the rough cut.

Just So You Know is a triumph for the editors Hanan Issa, Durre Shahwar and Özgür Uyanik. To preserve the authenticity of voice alongside the uniqueness of each author is proof of commitment to the principles of lived experience. May this be the first of many volumes.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.