Geraint Talfan Davies reviews biographies of two men who shaped Britain in the twentieth century.

Book Reviews:

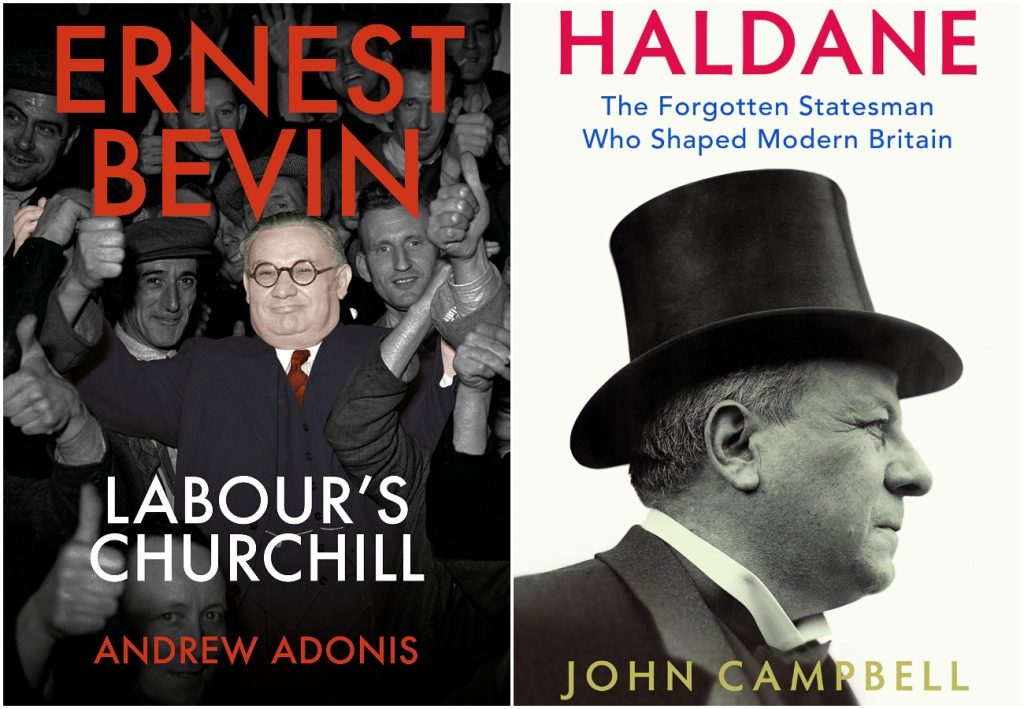

Haldane, The forgotten statesman who shaped modern Britain by John Campbell (Hurst )

Ernest Bevin, Labour’s Churchill by Andrew Adonis (Biteback Publishing)

By coincidence this summer has seen the publication of political biographies of two men who played crucial roles in shaping Britain in the twentieth century – in different ways and in different times – and yet have been overshadowed by others. They were Lord Haldane, in the first third of the century, and Ernest Bevin, for most of the second.

Haldane’s voluminous achievements, including his vital but truncated contribution to the winning of the First World War, have been obscured by the primacy of Asquith and Lloyd George, while Ernest Bevin’s contribution to winning the Second World War (and the subsequent peace) has struggled in the shadow of Churchill and Attlee and, in the matter of the subsequent peace, Bevan and his NHS.

Lord Haldane, or the 1st Viscount Haldane to give him his full title, is the subject of a deeply researched and admiring, although by no means hagiographic, work by John Campbell: Haldane, The forgotten statesman who shaped modern Britain. (Campbell is not to be confused with another John Campbell, a biographer of, among others, Nye Bevan).

In Ernest Bevin, Labour’s Churchill, Bevin gets an equally admiring but briefer treatment from Andrew Adonis, the Labour peer, a leading light in the Blair-Brown governments and a still resolute champion of the pro-European cause. Both authors set out to remedy the neglect of the reputations of their respective subjects, and in both cases see a relevance to modern political maladies.

Both Haldane and Bevin were born in the Victorian era, 25 years apart, Haldane in 1856 and Bevin in 1881. In many ways they could not have been more different, coming as they did from opposite ends of the social scale.

Bevin, orphaned at the age of eight, was from the rural working class in Somerset. He graduated to a horse-drawn cart selling mineral water in rapidly growing Bristol, before being drawn into trade unionism, eventually becoming the creator of the Transport and General Workers’ Union.

“Bevin, baptised by full immersion at the age of 20, was a Baptist Sunday School teacher and a lay preacher until lapsing in his forties.”

Haldane, on the other hand, was a ‘well-bred Scotsman’ whose fifteenth century forebears were Scottish ambassadors to France and Denmark while later Haldanes were, variously, members of the pre-1707 Scottish Parliament, a professor of Greek, a governor of Jamaica, high ranking soldiers and an Admiral.

From hardship Bevin was drawn, via unionism, into public service; for Haldane, from a starting point of immense privilege, public service was inescapable.

Both men were deeply conscious of the spiritual side of life. Bevin, baptised by full immersion at the age of 20, was a Baptist Sunday School teacher and a lay preacher until lapsing in his forties. Like many of his generation he saw socialism as an extension of Christianity.

Haldane was from Scottish Calvinist stock and, like Bevin, underwent adult baptism (albeit under loud protest), but orthodox religious belief did not survive a year of philosophical study at the age of 17 at Göttingen University in Germany, during which Hegel and Schopenhauer became two of his guiding lights.

Equipped with the highest academic honours from Edinburgh University, Haldane’s progression in the world of law and politics was impressively swift, although not without precedent: an unsuccessful Liberal candidate in the 1880 General Election at the age of 24, and elected five years later for a Scottish seat, Haddingtonshire, better recognised today as East Lothian.

Those were days when MPs were unpaid and often pursued parallel careers. Haldane made parallel progress in the law becoming, in his early thirties, one of the youngest QC’s of his day. The amalgam of philosophy, law and politics meant a three-dimensional life of the mind, albeit with a strong pragmatic bent that he applied with prodigious industry to necessary preparations for war, the expansion of education and the reform of government.

Bevin’s early career traced a very different arc: attending classes organised by the WEA (an organisation that Haldane, a lifelong supporter of adult education, had supported when it was formed in 1903), organising a Bristol Right-to-Work Committee in 1905 and, in 1910, during a dock strike at Avonmouth, urging his fellow carters to join an existing union rather than form their own. They joined the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Workers’ Union and Bevin became, six months later, their £2 a week organising secretary.

It was a period of widespread industrial unrest. Within a year Bevin had recruited 2,000 members and was intervening well beyond Bristol, including the 1911 port strike in Cardiff where the employers had attempted to break a strike by using non-unionised ‘blackleg’ labour.

“It was said at the time – rather hyperbolically – that Haldane was almost as popular as Lloyd George in Wales.”

Two years later the south Wales dockers presented Bevin with a gold watch and chain. Only a year later, on the eve of the First World War, he became one of the union’s three national organisers.

With the 1914-18 war over, Bevin was convinced that ‘we need fewer unions and more trade unionists’ and set about seeking amalgamations. In 1921, through force of personality and not a little guile, he brought fourteen unions and 250 officers together in the Transport and General Workers Union.

By the time of his death it had become the largest union in the free world. The T&G, says Adonis, ‘gave Bevin national power; the power to speak for the working class in a way no labour or trade union leader had done before or since.’ It was this strong base that made him such an effective minister in Churchill’s wartime Cabinet, even touted by some as a replacement for Churchill. Both men were characterised as British bulldogs.

Judged by crude Cabinet rank, arguably Bevin surpassed Haldane. The latter was Secretary of State for War from 1905 to 1912, and Lord Chancellor in both Asquith’s Liberal Government from 1912 to 1915 and Ramsay Macdonald’s first Labour Government that lasted only six months in 1924. Bevin, on the other hand, was Minister of Labour and National Service from 1940 to 1945 (having been elected to Parliament unopposed to make it possible) and Foreign Secretary from 1945 to 1951 in the Attlee Government.

That said, this is not a contest. Both men made invaluable contributions to winning the respective world wars of their time: Haldane, creating an effective structure for the Army; Bevin, an effective labour system.

Bevin was also able to reach those parts of the population that Churchill could not reach, given his pre-war record and reputation, not least in south Wales. The resulting mobilisation was more effective than that of Germany or Italy.

After the war, Bevin, as Foreign Secretary – and always an anti-Communist – harboured no illusions about Stalin, and even had to brace some of his American colleagues to the task. He also resisted ideas for fragmenting Germany, favouring instead the creation of a West German state (despite his own British Imperialist inclinations).

Haldane’s contribution to winning the First World War, on the other hand, was made before the war had even begun, through his role as Secretary of State for War. During this time he applied his rigorously rational mind to the modernisation of the military hierarchy and fighting forces, through the creation of an Imperial General Staff, the British Expeditionary Force and the Territorial Force, known later as the TA. It is generally regarded that the BEF, fighting alongside French forces, was crucial in halting the German advance and preventing the fall of Paris to the enemy.

There is a poignancy about this. Haldane was dropped from Asquith’s coalition Cabinet in 1915, at Bonar Law’s insistence, because a scurrilous newspaper campaign alleged that Haldane’s familiarity with Germany and diplomatic visits to the Kaiser rendered him suspiciously pro-German.

It was a gross calumny for which Asquith never apologised to his friend. The most telling response, Campbell points out, was the fact that at the war’s end the British commander, Earl Haig, went straight from the victory parade to Haldane’s home to deliver a copy of his published Despatches inscribed to ‘the greatest Secretary of State for War England has ever had.’

Haldane’s reform of the military was but one manifestation of a seemingly unending institutional creativity. In 1892 he suggested the creation of a Ministry of Labour. It materialised in 1917. In 1903 he was midwife to the creation of the Workers’ Educational Association and in 1921 the founder of the British Institute of Adult Education, later NIACE. In 1909 he proposed the creation of the Secret Service Bureau that in time became MI5 and MI6.

Much influenced by Germany, particularly the links there between universities and industry, he applied himself to the development of university education. In 1895, with Sidney and Beatrice Webb, he founded the London School of Economics.

Innovative. Informed. Independent.

Your support can help us make Wales better.

One of its early directors was William Beveridge, who, in the 1940s, became the architect of the welfare state. In 1907 Haldane was also involved in the founding of Imperial College. He helped reorganise university education in London, Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin and Belfast and from 1916-18 chaired a Royal Commission on the constitution of the University of Wales.

Lest anyone think that Haldane took such responsibilities lightly, Campbell points out that in Wales the Commission held 31 sessions for examination of witnesses and 36 sessions ‘for deliberation’. The report was greeted with much acclaim for recommending a Court of the University that would act as ‘a Parliament of higher education’.

It was said at the time – rather hyperbolically – that Haldane was almost as popular as Lloyd George in Wales. But, in the long term, the real import of its recommendations was in the increased powers given to the constituent colleges. By now those colleges are in the driving seat; indeed, they own their individual cars. A functioning University of Wales is no more.

Haldane was also fitting this in, again at Lloyd George’s invitation, with chairmanship of a Committee on the Machinery of Government that reported in 1918. Had its report not fallen foul of both the politics and the economic depression of the time it might have borne more fruit earlier. It is chastening to think how slow institutional reform can be in this country.

Haldane’s committee recommended the creation of a Ministry of Health. This, at least, was realised a year later. Other recommendations took more time: a ministry of Education (1944), a neutral Speaker of the Lords (2006), a Ministry of Justice (2007) and a Supreme Court (2009). Better late than never.

Despite all this he also found time to sit on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in which role he was hugely influential in shaping the constitution of Canada, always favouring the devolution of powers to the Canadian provinces, much to the chagrin of the Federal Government. How one wonders, would he have approached the principle of subsidiarity in the EU?

“As a friend of the Rothschilds and Einstein, he would not have admired Bevin’s strain of anti-semitism, common though it was at the time.”

The two men represent a remarkable contrast: one co-opted for war, the other dismissed in the middle of a war; one rounded by a rich education, the other forged by the lack of it; one a lover of Germany, the other hating it, but neither seeing beyond the Imperialism of the era of their birth; both members of the Labour Party, the one by the circumstances of birth, the other, eventually, perhaps finding a necessary route to usefulness; both of them men of deep conviction but not ideologues; both wanting to make things work better.

Bevin reserved much scorn for ‘intellectuals’ – he may have felt it was obligatory – but he would surely have admired the way Haldane consistently applied that intellect to practical ends, and admired, too, that those ends were not defined by the class from which he, Haldane, came. He was, in fact, a bridge between the Liberal and Labour eras.

In return Haldane would have admired Bevin’s realism and his statesmanship (not to mention his commitment to German reconstruction) although, as a friend of the Rothschilds and Einstein, he would not have admired Bevin’s strain of anti-semitism, common though it was at the time.

In the face of the differing arrays of achievement of their subjects, both authors feel obliged to ask what their subjects would be doing today faced with our current problems. Adonis suggests Bevin “would be organising the millions of low-paid workers, particularly the five million-strong and largely non-unionised social care and gig economy sectors”. Campbell wonders how Haldane’s systemic approach would have tackled the current disastrous split between health and social care.

The need for such speculation is depressing, for although the social and economic problems we face today are no less daunting than at the start of the twentieth century, our politics feels more fumbling and febrile and inadequate to the task. These two fascinating volumes about two men of quality, insight and resolve show that it need not be so.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.