Our current election practices do not allow everyone a confidential vote, writes Nathan Owen.

With Senedd and Police and Crime Commissioner elections on the horizon, important conversations continue to be had about the diversity of our democracy.

In some respects, Wales can boast a better track record than most. In 2003, we became the first country in the world to have an equal number of men and women in parliament.

Today, as the fifth term of the Senedd draws to a close, 29 of its 60 total Members and eight out of fourteen Welsh Cabinet Ministers are women.

But Wales is in danger of rolling back on the progress made in gender equality. After 14 years of service, Plaid Cymru’s Bethan Sayed has chosen not to seek re-election citing the impossibility of balancing political and family life as a key factor behind her decision.

With recent polls suggesting that only a third of female candidates in this year’s elections are contesting ‘winnable seats’, a shift back to a male dominated Senedd seems highly likely.

On race equality, there has been far less progress. There have only been four male black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) Members of the Senedd in its 22-year history and, to the institution’s enduring discredit, no BAME women have ever been elected.

Whilst steps have been made in the right direction, it is clear that there is a way to go before the Senedd can claim to be truly reflective of the diverse population it serves.

“Just one in ten blind voters were able to vote independently and in private at the 2019 UK General Election.”

But for some voters, like blind and partially sighted people, democratic disenfranchisement goes far beyond political representation.

Fundamental democratic rights are being systematically denied to this group because our voting system is simply not accessible to them.

Research by sight loss charity RNIB found that just one in ten blind voters were able to vote independently and in private at the 2019 UK General Election.

For those that voted at a polling station, one in four had to rely on a member of staff to help them cast their vote, essentially forcing them to share their voting preference with a stranger and leave the polling booth hoping that person had carried out their wishes.

How can our democracy profess to be fair or representative when such systemic barriers exist to civic participation at the most basic fundamental level?

An ‘archaic’ pen and paper based system

So what provisions are in place to support blind and partially sighted voters?

All current voting methods for elections held in the UK require the voter or their nominated representative to mark a box on a standard format ballot paper.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

By law, polling stations must have a large print version of the ballot paper available. Voters are able to use this as a reference but cannot use it to record their vote.

When voting by post, voters can request information be sent to them in an accessible format like braille or large print, but again, voters are required to mark and return the standard version of the ballot paper.

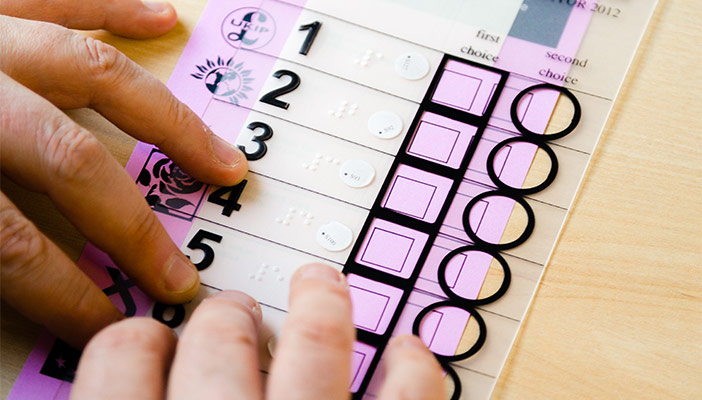

Polling stations must also have a tactile voting device. This is a plastic template which is intended to be put over the ballot paper to help voters to locate the position of the boxes on the ballot paper and make their mark.

What the device doesn’t do, is inform the voter which box relates to which candidate.

Any voter wishing to rely on the tactile voting device alone would be dependent on knowing and memorising the order of the candidates as printed on the ballot paper. The device is also quite flimsy, and users report accidentally spoiling their ballot papers when trying to cast their vote.

“Most blind and partially sighted voters have to rely on another person to mark their ballot for them.”

In practice, because these adjustments don’t guarantee an accurate and private vote, most blind and partially sighted voters have to rely on another person to mark their ballot for them.

Our voting system forces disabled people to forgo their rights to privacy and independence by making them choose between relying on someone else or not knowing whether they have cast their vote correctly.

Some people try to find their own work arounds, like using a magnifier or assistive technology apps on their smartphones to read the ballot paper. But this is not possible for everyone.

Over 80 per cent of the 121,000 blind and partially sighted people in Wales are aged over 65 and Public Health Wales have identified that disabled and older people are more likely to be digitally excluded than other groups.

Additionally, some respondents reported that polling station staff had not allowed them to take the large print resources with them or use their phones inside the polling booth.

The current provisions were declared unlawful in 2019, with the judge describing a system that expects a blind person to mark ballot papers without being able to know which candidate they are voting for as “a parody of the electoral process.”

“Braille, large print, digital and audio are not routinely provided, and many people don’t feel confident to make a request or know who to contact.”

But two years on, on the eve of Senedd elections, we have yet to see any solutions implemented to allow this group to exercise their democratic rights on an equal basis to everyone else.

The right to make an informed choice

The issue of equitable access goes beyond the voting day experience.

More than half of blind people said they couldn’t read any information about elections sent to them by their local council, including polling cards. That’s despite the right to receive information in an accessible format being protected under Equality Act.

For many people, something as simple as receiving information by email or in a larger font would enable them to access information on the same basis as everyone else.

But local authority electoral services usually send information out in a standard format to all electors in an area.

Accessible formats, like braille, large print, digital and audio are not routinely provided, and many people don’t feel confident to make a request or know who to contact.

It is simply not acceptable to assume a person with sight loss can rely on a sighted person to read out information for them, and it shouldn’t be up to individuals to seek out information in their required format to enable them the opportunity to participate equally in our democratic system.

Getting the basics right

Efforts are being made to increase the diversity of voices in our political system which has long excluded them.

New and welcome initiatives like the Access to Elected Office fund seek to remove barriers to participation and encourage greater political representation from disabled people.

“We need to solve these basic but fundamental problems if we are to ever consider our society to be truly democratic.”

But how far can these initiatives really take us when our systems are so rigid that they don’t give people the tools to vote by themselves or access to the information needed to make an informed decision?

We need to solve these basic but fundamental problems if we are to ever consider our society to be truly democratic.

RNIB are calling on all governments and local electoral services to implement a reformed voting system which guarantees a private and independent vote to all voters in future elections.

We have worked with the Electoral Commission on training resources for polling station staff to improve their understanding of sight loss and to help them to support voters on election day.

We have also produced a pocket guide for voters, which is available in a range of accessible formats including large print, digital, audio and braille.

It provides information on the elections, the different voting options available and explains the support and adjustments you are entitled to.

Over the last few decades, access to services for people with sight loss has improved. Widespread use of assistive technology has allowed people more freedom, but perhaps this has also allowed decision makers to ignore demands for reform of systems that are still fundamentally unfair.

If we want to hold up our heads and live in a democracy which doesn’t discriminate against disabled people, people with sight loss should be able to vote as privately and confidently as everyone else.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.