Merlin Gable reviews cardiff cut, and wonders if its portrayal of alternative lifestyles and rebellion still speaks to readers twenty years on.

It is not for me to judge whether Wales is yet ready for Parthian/Modern. The whirlwind of time spins ever faster and we find books a mere two decades old may now be published with the implication of being ‘modern classics’ where once they might simply have been second editions. I can well imagine the featured writers have mixed feelings given they’re all quite alive and well, unless, like Morrissey, they enjoy being a living classic.

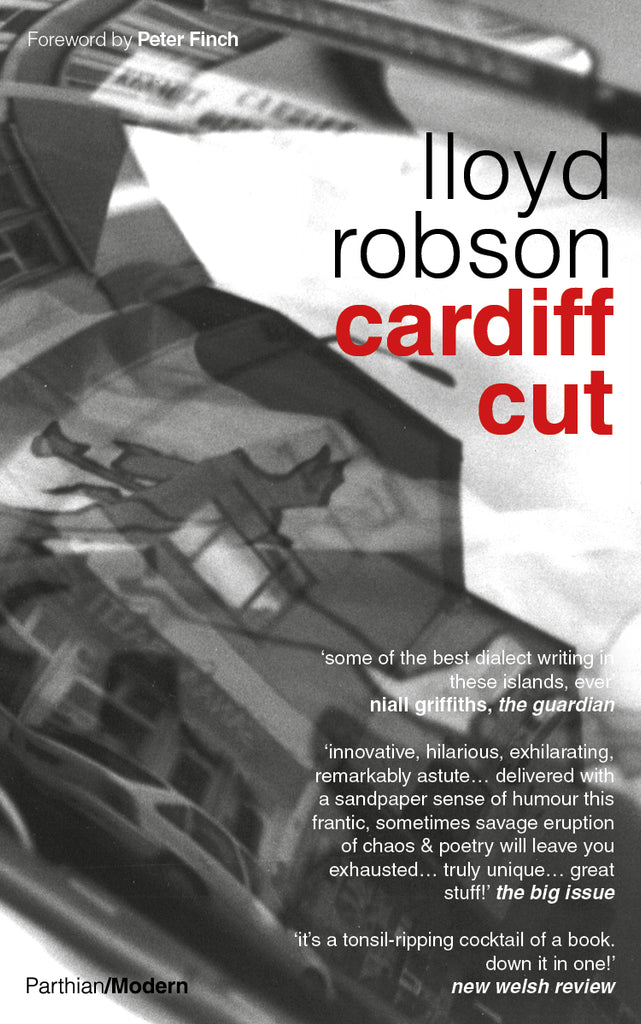

Instead, I’m merely concerned for today with Lloyd Robson’s worthy inauguration to the stable with a new edition of his cardiff cut, the narrative work (‘you wanna read it like a novel then read it like a novel… it’s in your hands, both literally & literarily,’ he writes in the acknowledgements) he first published in 2000.

What does cardiff cut have to say to Cardiff, and to Wales, in 2021 – and what does it have to say to younger generations of readers and writers, some of whom have continued the tradition of city narrative in their own work about the capital.

For full disclosure, I was five years old when cardiff cut was first published and had little to say at that age about sex and drugs and Splott and Adamsdown (some of the book’s main concerns). But, to counter this obvious weakness in my suitability as a reviewer, I do now live in Cardiff. This makes for perhaps a more interesting question posed in reviewing the book: what does cardiff cut have to say to Cardiff, and to Wales, in 2021 – and what does it have to say to younger generations of readers and writers, some of whom have continued the tradition of city narrative in their own work about the capital? Taking its canonisation as a modern classic as a sign that it encapsulated, at least for some, what Cardiff was at a certain time, the question becomes less whether that form of representation is a good one but rather whether it still speaks to the present and, if not, what form might better do so.

And cardiff cut feels, certainly, of its time. This is neither a bad nor a condescending thing. The writing is self-consciously avant garde, and bullishly vernacular, as we are whisked around Cardiff in the head of someone who certainly feels they know it all (more on this later) and certainly knows what they like: drinking, drugs, dive pubs, scurrilous stories, taxis, girls, and shit. (There is, by the way, a question to be asked about Welsh male writers in the nineties and their narrative preoccupation with shit. But that’s for another article.)

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

This is both a good and a bad thing. There is certainly a great deal of affectation in the writing, for instance when the narrator comments ‘drop in some icecubes & take a sip (a sip? what am i saying)’ as though even the sophistication suggested by the word sip – or by sipping – is too much. It’s not really worth worrying, as Peter Finch does in the modern edition’s foreword, whether anyone actually speaks like this. They do and they don’t. What the writing does is collect together a series of cues that someone in the know will use to identify with place. We also see it in the semi-obsessive naming of streets and particularly their intersections, as well as the bars and shops that were live references at the time but now speak to the ghosts of a city that has changed substantially.

There’s an identifiable youthful individualism; even where other characters are concerned they exist as tribes rather than communities.

The ghosts can be productive too. I enjoyed the lines ‘could an innocent bouncing queen street park place implode & blow dylan’s bar away? (an accident; volcanic redbrick ashtray; a gutted listed building).’ Dylan’s Bar is long gone now, and more and more listed buildings are gutted. The Cardiff that Robson was writing at the turn of the millennium – there are references to the devolution referendum and other events – has continuities with the modern-day city as well as differences.

There’s an identifiable youthful individualism; even where other characters are concerned they exist as tribes rather than communities. There are the ‘girls on chocolate come downs, the blokes growing impotent but too stoned to care’ in the queue at the Spar late at night (they ask for ‘beer, bogroll, loaf of bread, disposable lighters, chocolate, rizla, cigarettes, o & a coupla pork pies’, since you ask). The enemies are simpler too: the ‘prozzies, arseholes, mounted police on undercover coming to the sound of car alarms’.

Although amusing and evocative in its way, it’s a register and a worldview that, as I have written previously in the welsh agenda, I think has had its day. Ultimately it doesn’t feel like it can speak to the post-ironic world we now live in. Things are a little too serious, a little too desperate, for cocksure verbal rebellion – you have to make sure people get the point now, which can result in at once more subtle and less subtle writing. Perhaps we are much more aware now of the relationships between people and places and are under more pressure to make ourselves understood across greater divides of experience, so certain outward forms of difference are less emphasised.

At its low moments, cardiff cut can feel like it is just listing activities undertaken with gleefully distasteful detail. It doesn’t get us far towards feeling. Where the narrator writes that ‘it ties me. this inability to tell real from reality, i know what i think i know but the real leaves me panicky (rapid fade to black&white…)’ and might imply a divorce from reality that is at least partly chosen – through drugs, drink, social dissent – now the forces of reality and unreality play out in our everyday lives on the internet, in social media, in the news, and the consequences are far scarier.

Ultimately, even the text promises a nonchalance which can’t be sustained totally. The glossary at its end is proof of that, revealing a peppering of allusions which betray a studied knowledge and interest in Cardiff’s history which is nothing like the proudly skin-deep narrative voice.

cardiff cut

Lloyd Robson