Eluned Parrott sets out the potential of physics to benefit the economy and makes a case for its inclusion in Wales’ innovation strategy.

Three people born in Wales have won a Nobel prize. Two of them — Bertrand Russell (Literature in 1950) and Sir Clive Granger (Economics in 2003) — were educated entirely in England. Only one had their compulsory education in Wales. It was a physicist: Brian Josephson.

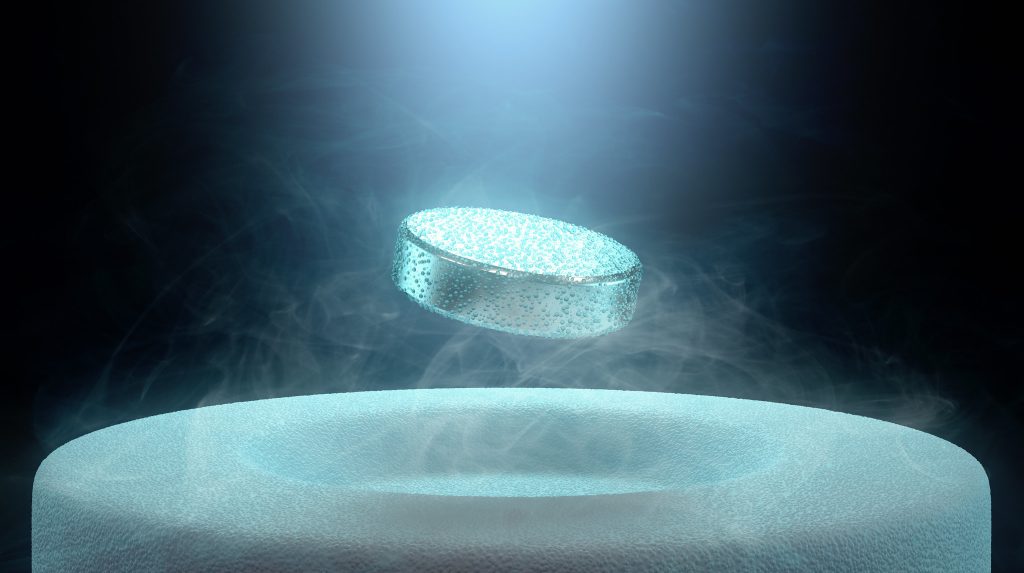

Born in Cardiff in 1940, Josephson completed his school education at Cardiff High School before going to Cambridge, where his work on superconductors and quantum tunnelling was recognised with the 1970 Nobel Prize for Physics. It’s a great source of inspiration for the next generation.

Josephson was recognised for theoretical work from his PhD, but it’s worth remembering that not all Nobel laureates are from universities. Several private companies have produced physics recipients — none more notable than the legendary Bell Labs. Their winners include a 1953 research and development team for their work on semiconductors, an industry that has evolved into one of Wales’s own success stories.

Wales could be well placed to take advantage of the ongoing tech revolution if we play our cards right.

So what would it take for Wales to nurture the next Bell Labs or another tech cluster as successful as our semiconductor industry? While it might surprise outsiders, Wales could be well placed to take advantage of the ongoing tech revolution if we play our cards right.

Research by the Centre for Economic and Business Research (CEBR) on behalf of the IOP demonstrates the fundamental importance of physics-based businesses to the Welsh economy. In 2019, the sector contributed 10% of Welsh GDP and full-time employment; that’s £7.3bn and 113,138 jobs. The areas in which physics-based businesses operate are also incredibly broad, underpinning everything from medical diagnostics to the aerospace industry. Physics is a fundamental science with a huge range of possibilities.

The story is one of growing success across a decade, with turnover rising by 36% — the fastest rise of the four UK nations and well above the UK figure of 24%. There has also been substantial growth in employee pay, up 41% in the same period — also the largest increase in the UK.

Robust debate and agenda-setting research.

Support Wales’ leading independent think tank.

But a cursory glance at the Welsh economy and its history should put paid to any complacency. Wales still has the lowest R&D spend per capita of the UK nations and comparative regions of England. We also have fewer people working in R&D roles. There’s an opportunity here for our nation to grow.

The Welsh Government’s next step will be to publish a long-awaited innovation strategy. Given the figures above, it’s vital that the role of fundamental science is properly recognised and embedded in that strategy. Without strength in foundational subjects like physics, the edifice you build on top will be fragile.

The UK Government is emphasising science and technology unashamedly, understanding innovation as tech-driven and high-growth. The Welsh Government is taking a different approach, broadening its conception to allow for social innovation and a focus on the foundational, everyday economy.

A knee-jerk reaction is to assume this breadth could hamper physics’ impact, but I disagree. There’s room for both definitions here. Innovation is a mindset, not a set of handcuffs. How Wales pursues innovation in future — and the innovation strategy will be crucial in defining and supporting this — should be more about usefulness and its measurement. This is, after all, what separates innovation from discovery —whether something is applicable and useful.

As many as 60% of those who teach physics in Wales’s secondary schools did not study it for their degree or complete their teacher training in the subject.

But back to Josephson. He has spoken about how Emrys Jones, his teacher at Cardiff High School, introduced him to physics and spurred him to pursue it at Cambridge. But the situation today raises some uncomfortable contrasts. As many as 60% of those who teach physics in Wales’s secondary schools did not study it for their degree or complete their teacher training in the subject. A holistic approach to innovation must link closely with education and skills development if we are to maintain our high-tech industries.

That is, of course, if “maintenance” is the limit of our ambition, but there is no reason why it should be.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to see a Welsh physicist winning the Nobel prize again in the 21st Century and doing so having been educated entirely in Wales? Shouldn’t it be an attractive and ambitious choice for young people to stay here in Wales and build their future in a vibrant innovation economy? Isn’t it possible that by giving both social and technological innovation sufficient weight, we could have a healthier and wealthier Wales?

There are a huge number of links to bring together to build that future, but it is heartening to know that some of the foundations are in place. As an astrophysicist would never say, if you shoot for the stars you might hit the moon. At the very least, it is an ambition worth having.

This article is part of our series of commissions on the theme of work. Find out more here, and send us your pitch if you have ideas on the topic.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.

Comments are closed.