Ken Moon explores the history of wild swimming and free dipping and uncovers its revolutionary connection to the right of access.

In the modern era the Covid 19 lockdown highlighted the importance of community access to local landscapes for many of us. And one of the ways people started to reconnect with their local landscape was through dipping and wild swimming. In Rhondda Cynon Taf groups like Rhondda Valley Dippers sprung up encouraging people to take a dip in nature.

But dipping and wild swimming in local streams and rivers is not anything new and many people have memories of doing so as a child or know people who do. Whilst these are both past times many people have been discovering and rediscovering for the first time since the pandemic, many of these locations have a history of use which stretches back generations.

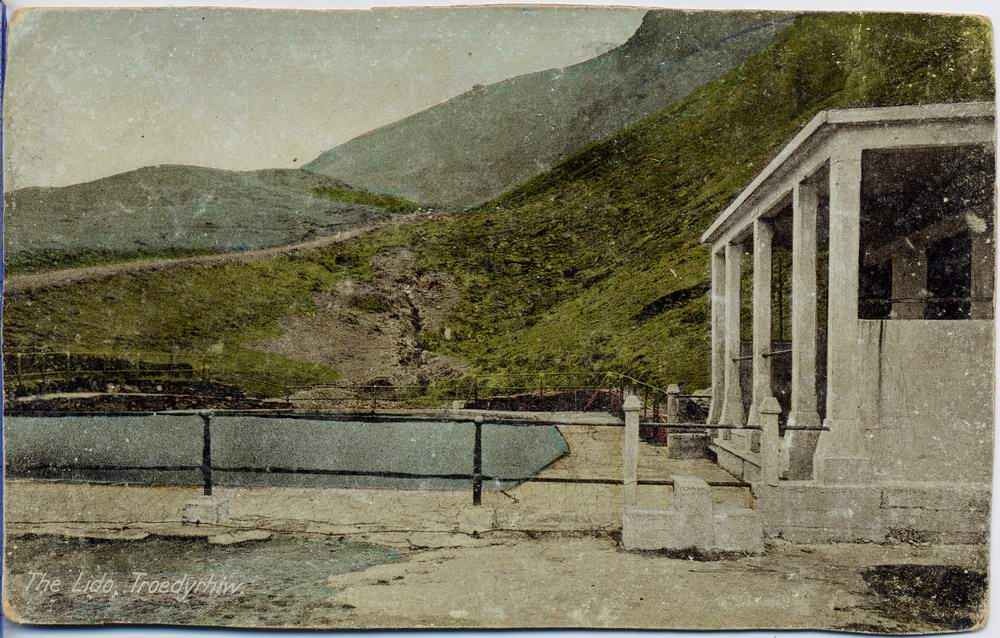

Troedyrhiw Lido

In Troedyrhiw for example many older residents have fond memories of Troedyrhiw Lido. At the height of the great depression, unemployed miners persuaded the landowner to allow them to construct a paddling pool for the local community. The area was a local beauty spot where a natural spring fed into a pool where the miners had built a small paddling pool site the previous summer.

The 1930s were an extremely challenging time for many industrial communities, unemployment levels were high and social injustice rife. To help support the community, the landowners agreed to fund the costs of the materials and the miners gave their time and labour for free. And the right for all members of the community to bathe freely in the new Lido was agreed.

This spirit of self-help exemplified in Troedyrhiw in the 1930s was of course nothing new. Before the advent of the Welfare state communities across Wales made use of and created their own local assets to help meet local needs. Without state intervention in the provision of public assets the industrial communities of Wales had been finding many creative ways to create their own support infrastructure.

The infrastructure that we’re now allowing to fall by the wayside in return for the promise of lower taxation, is the very infrastructure our communities scrimped, saved, and sweated to build.

For example, miners, and other industrial workers gave a small proportion of their weekly pay packet towards the building of welfare halls, schools, medical facilities, libraries, churches, and many other key aspects of local infrastructure. Mutuality and mutual support created the infrastructure which take for granted today, which has become neglected, and in many instances lost.

Yet this infrastructure was so crucial to community wellbeing that much of it was assimilated into the Welfare State. For example, schools were assimilated into municipal educational authorities, libraries became part of county leisure services, and miners’ hospitals became an intrinsic part of the National Health Service.

A small portion of chapels, welfare halls and institutes are still valued community assets whether in private, community or public ownerships. Some of those that have been allowed to fall into a state of disrepair, like the Cefn Fforest Miners Institute, are now being valued once again, rescued by their local communities and brought back to their former glory.

Whilst this infrastructure was created within living memory many of us who live in these post-industrial communities have largely forgotten that our forebears literally built the very foundations of the welfare state. The infrastructure that we’re now allowing to fall by the wayside in return for the promise of lower taxation, is the very infrastructure our communities scrimped, saved, and sweated to build. Different times perhaps.

Access for well-being

The Welfare State itself was established out of a grudging recognition that those who had fought and died in two World Wars finally deserved a ‘home fit for heroes’, rather than the unemployment and slum housing which preceded them. Alongside the debates which raged around the creation of the Welfare State, improving our rights of access to nature for community wellbeing was another hotly contested matter.

In The Book of Trespass, Nick Hayes wrote of how the Report of the National Parks Committee of 1947 (or Hobhouse report) ‘…proposed a fundamental change to the access laws of the countryside – a full right to roam over all uncultivated land in England [and Wales], so that people could actually experience the land for which they had fought. It was proposed as a corollary to the NHS, providing health and recreation, the prevention of illness before the need for a cure.’

Nick Hayes goes on to explain how landowners, many of whom were MP’s or members of the House of Lords, lobbied hard against a full right to roam. So much so that by the time the Bill for the National Parks and Access to the Countryside became law in 1949 a full right to roam had long since been ‘redacted from the debate’.

What we got instead was a reassertion of ‘…the prevailing philosophy that the public constituted a threat to the countryside and must therefore be corralled away from its woodland, lakes and plains into areas specifically designed for recreation’. What we were eventually left with were just ten areas of land opened for public recreation, and the structure for the registration and maintenance of footpaths.

Yet as any member of the Ramblers can tell you, many footpaths are once again under threat of being lost, and our rights of access to the countryside in a wide variety of ways, not only remains very limited, but are still being eroded. Three quarters of a century later and what was hailed as a people’s charter for increased access to the countryside has proven to be ‘a major success for the landowning establishment’.

Had our right of access to simply be in the countryside been enshrined into law, like the broad land access rights enjoyed by many of our European neighbours, then perhaps our health stats here in Cymru might not be quite so poor. But a lack of access rights did not stop those who lived and worked in the industrial communities of Wales from accessing the land around where they lived for their health and wellbeing.

Our right to simply be in the landscape is as hotly contested today, as it has been since William the Conqueror first invaded Cymru and claimed all the land as the rightful property of the crown by right of conquest, including what we know today as the Crown Estate.

And judging by the popularity of dipping, it doesn’t stop many of us today either.

On the completion of the work to build the Troedyrhiw Lido in the summer of 1934, the landowners gifted the deeds of the land to the Lido committee.

Troedyrhiw Lido then is a great example of how one Welsh industrial community was able to secure their own rights of access to their local Ffridd, and presents us with an interesting model for how we can go about doing so again. Through their own industry the miners secured the right to the land on which their Lido stood.

And today groups like Rhondda Valley Dippers are a great starting point for encouraging people to access nature for their own health and wellbeing. But our rights to our favourite dipping spots, or any other favourite places, are not enshrined in law, and are still being challenged and contested through the courts.

Our right to simply be in the landscape is as hotly contested today, as it has been since William the Conqueror first invaded Cymru and claimed all the land as the rightful property of the crown by right of conquest, including what we know today as the Crown Estate. Our collective rights to our shared commons have been eroded by the rights of exclusive ownership ever since.

Every walk, run or dip in a place where we have no permission to be, is a reassertion of our ancient collective right to access to our local landscapes for our own health and wellbeing. Every time we assert the right to access our shared commons and to create our own local assets, we’re engaging in a revolutionary act. But it takes more than this to maintain a revolution.

By 1941 Troedyrhiw Lido was starting to suffer from the effects of vandalism, and whilst residents who grew up in the 1950’s have fond memories of the Lido continuing to be a popular picnic spot for families, by 1964 the site was out of use and in a state of major disrepair. Community rights of access to landscape require maintenance in much the same way as our local community assets do.

If we are to secure our local assets for future generations it is not enough for us simply to access them, we must feel as though we own them too. Because it is only through a sense of ownership that we might feel that such assets are worth looking after, even when hard times improve. If we all felt a greater sense of ownership over the NHS today, would we have allowed it to suffer the neglect we have?

Groups like Rhondda Valley Dippers, and the Troedyrhiw miners, are both colourful and insightful parts of our rich history and our long struggle to reclaim our shared rights of access to our landscapes. To dip, swim, walk, run, climb, ride, play, enjoy or simply be in nature is to live this history. It is to engage in the revolutionary act of reclaiming our own common rights of access, to begin the task of creating a new wellbeing economy for the wellbeing of future generations.

But the real act of revolution is not simply in accessing nature for wellbeing, or even in securing land or other assets, but in getting involved in the difficult, and sometimes mundane, task of looking after them from one generation to the next. Whilst the land around where we live, our Ffridd, may well be the greatest asset of our future wellbeing, the welfare state remains a sacred testament to our forebears’ great historical endeavours to create assets for our shared community wellbeing.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer. If you want to support our work tackling Wales’ key challenges, consider becoming a member.