Lydia Godden reviews an account of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike informed by interviews with miners and by the authors’ own reporting on the events at the time.

The social and political upheaval of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in Britain plunged many Welsh coalfield communities into an economic ice age that has shown little signs of thawing. The policies and political choices of Margaret Thatcher, coupled with the sheer pace of de-industrialisation, irrevocably devastated communities in Wales.

This subsequently led to ‘the rapid privatisation of nationalised industries, the shattering of organised labour, growing unemployment, the hollowing-out of mining and other working-class communities, and a steady increase in social inequality in British society.’

The Miners’ Strike was a time of solidarity and organising across Wales. Farmers in West Wales would send trucks piled high with food produce to feed hungry striking miners and their families.

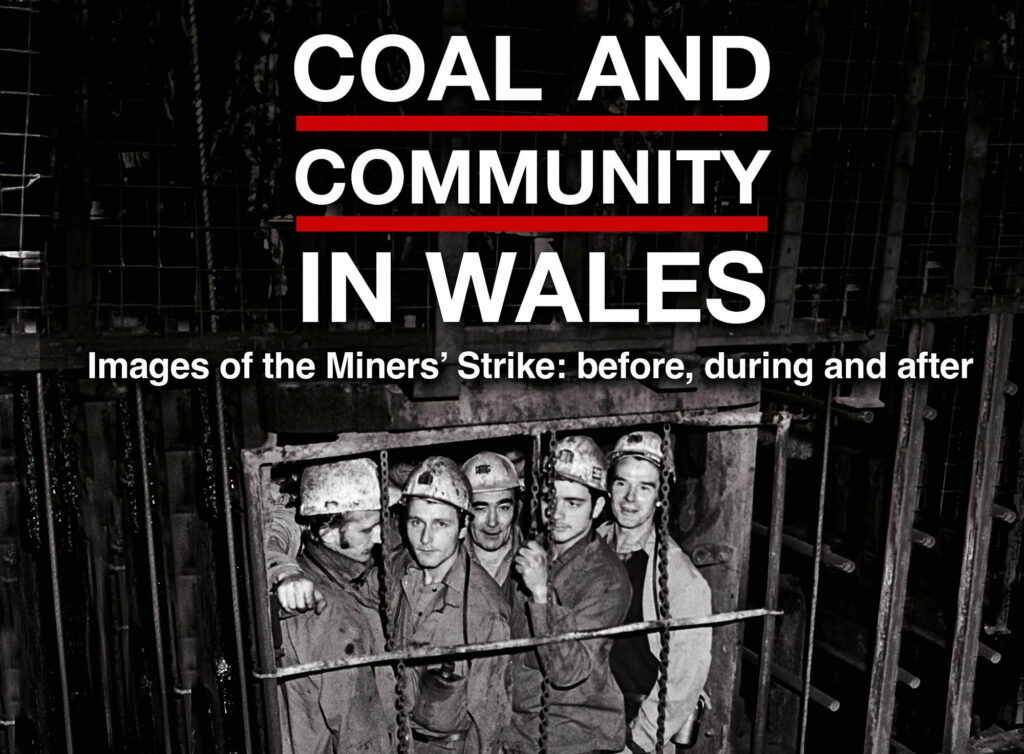

Coal and Community in Wales provides an insider’s perspective on the strike, with moving, gritty images, coupled with first-hand accounts. The book is imbued with feelings of loss, anger and pride – a story of ‘people fighting desperately for their livelihoods and communities.’

United we stand

The Miners’ Strike was a time of solidarity and organising across Wales. Farmers in West Wales would send trucks piled high with food produce to feed hungry striking miners and their families. It was also a turning point for others, a time of political awakening for many women in Wales. In the heavily gendered days of the 1980s, where many women had little place in public life, many rose to the fore, leading the many miners’ support groups across Wales.

As the author states, ‘The Miners’ Strike involved the women of the coalfield as much as the men. It led to many women becoming more involved in their communities and even entering politics. Perhaps the most prominent is Siân James, who supported miners’ families during the strike and later became the first female MP for Swansea East.’

Women were the backbone of the strike. In chapter seven, Maud Smith, who had lived through the 1926 General Strike, warned the women to prepare for a long strike. They sprang into action, raising funds for food parcels, appeals for donations, running soup kitchens, and organised raffles and coffee mornings.

The book includes powerful images of the many women who joined picket lines and protests, standing face to face and even clashing with police.

The significance of their efforts did not go unnoticed. After all, hunger and poverty were tactics employed by the Thatcher Government to undermine strike action by removing benefits rights for single strikers in the Social Security Act 1980.

The strike was also a time of great hardship. In chapter four, we meet Kath Morgan, who recalls: ‘We must have been living on £10 to £15 a week, and that’s being generous… it was very much a struggle.’

Growing up in the decades following mass pit closures, I remember my mother recounting how people had resorted to burning their furniture as a last resort to keep warm. Stories are what many in my generation rely on to understand the events of the Miners’ Strike.

For younger people, the book is a detailed account of that era, with first-hand accounts otherwise lost to history. The introduction explains the preceding decades, industrial disputes and debates leading up to the strike, such as the fact that ‘people in former mining communities still debate whether National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) President Arthur Scargill did the right thing in making the strike official across Britain without holding a full members’ ballot.’

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

The first chapter brings personal insights into the varied roles at Coegnant Colliery in Maesteg, from Norman Davies the hitcher to overman Spencer James. We are also reminded of the social and cultural impacts that mining and the wider legacy of collectivism had from the miners’ institutes, hospitals and libraries. The book makes clear how the ‘black gold’ that was coal built our communities: ‘Miners and their trade unions fostered a proud tradition of self-improvement and education, influencing and expanding the cultural and social life of their communities.’

‘If the police want a ruck, they can have one’

On clashes with police, the book acknowledges incidents, such as heavy-handedness with women and the high tensions often overrunning and resulting in arrests. However, the accounts note almost jovial interactions with the police expressing sympathies or even support for miners to one account sharing food with those on picket lines.

A real strength of the book is its continued relevance to today’s former coalfield communities.

To some degree, this potentially paints a rosier picture than what was experienced across coalfield communities. Indeed, close community ties often meant local police maintained ‘amicable relationships with neighbouring miners’.

While the authors note concerns that undercover soldiers may have been brought in to quash pickets at Port Talbot, the book does not reference coalfield communities’ suspicions that police used covert spying tactics during the strike. Government papers revealed in 2014 that surveillance including phone tapping was used against miners and their families, despite warnings around the legitimacy of such tactics. Some former miners claim to this day that undercover police spies were used to infiltrate coalfield communities long before strikes began in 1984.

Single use only in connection with the above mentioned book, no other use is permitted.

Pictures by : Richard Williams Photography

Was it worth it?

A real strength of the book is its continued relevance to today’s former coalfield communities. The final chapter traces the ongoing economic hardship, unemployment and worsened health outcomes back to the demise of industry following the defeat of the miners.

Striking miners and their families demanded ‘Coal not dole’ and warned, ‘Close a pit, kill a community’, and to a degree their fears have become a reality. While community spirit lives on and, as Anna Rankin explains, ‘people will do anything and everything to help you out’, the successive top-down policies of trickle-down economics have done little to rebuild former coalfield communities.

The book notes the ongoing legacy of coal mining in the hundreds of high-risk coal tips that sit above the Valleys. Wales may have recently seen the end of opencast mining but the nationwide opencast reclamation challenge now poses a huge financial and environmental burden.

Was it worth it? While the miners lost the strike, the book demonstrates how they left a legacy to be proud of and showed that community is worth fighting for.

Coal and Community in Wales. Images of the Miners’ Strike: before, during and after by Richard Williams & Amanda Powell is published by Y Lolfa.

You can read an insight into the work that led to the publication of Coal and Community by book author Amanda Powell in issue 72 of the welsh agenda.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer. If you want to support our work tackling Wales’ key challenges, consider becoming a member.