Following her eco-dystopian reflection on the prisons of the future, Heledd Melangell explores whether transformative models and the restorative laws of Hywel Dda could inform our approach to the Welsh justice system and prisons by the year 2100.

What will the criminal justice system in Wales look like in the year 2100? According to research from leading academics in the field at Cardiff University, the current trajectory suggests a dire state of affairs.

Wales has the highest incarceration rate in Western Europe and a system where individuals from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities are over-represented at almost all stages of the criminal justice system, and, in some cases, at a rate higher than it is in England. This adds to already horrifying data about racism in the prison system in England and Wales, which does not currently differentiate between the nations.

As it stands, Welsh Government and Whitehall policies that directly and indirectly influence the criminal justice system diverge and are therefore completely incoherent. This is illustrated by the way England prioritises issues such as ‘knife crime’, which is more pronounced in the large English cities. Despite some (seemingly inconsistent) communication, Wales is largely an afterthought. This leads to chaos in the criminal justice system and to what Rob Jones and Richard Wyn Jones have described as the ‘jagged edge’ of justice in their book The Welsh Criminal Justice System: On the Jagged Edge exploring this important matter (Jones & Jones, 2022). Personally, prison has been nothing but a toxic burden on my life. I have had to watch helplessly as the lives of friends and family were destroyed by the trauma and stigma of serving custodial sentences.

I’ve only ever seen vulnerable people in crisis, not the evil psychopaths the tabloids would have you believe. Their lives were already in a dark place when prison compounded the state of helplessness they were already in. A chance at digging themselves out of their hole is what they really needed. Instead, their bodies were transformed into fodder for the Prison Industrial Complex. A captive workforce without the most basic rights.

However, is there such a thing as a Welsh Prison system? According to Richard Wyn Jones and Robert Jones, this is questionable. The book refers to the frequently used image of the stool of governance to describe British democracy, with the judiciary, the executive and the legislative making up its three legs. Due to the piecemeal devolution of powers to Wales, Welsh devolved governance became a two-legged stool.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

The metaphor holds up in illustrating how clearly dysfunctional governance is without its last leg, namely the judicial system. I would argue that even the UK government with its three-legged stool isn’t working, but as mentioned above, statistics show that the Welsh situation is even worse than that of England.

It feels to me as if England is attempting to consolidate its power (the union) through the criminal justice system.

Despite calls from the Silk Commission in 2013 and the Justice in Wales for the People of Wales 2019 report to devolve justice to the Senedd, there has been no sign of this being on the horizon. Planned and existing mega prisons in Wales show no plan to separate the Welsh and English criminal justice systems in the future either. In fact, with talks of additional ‘super prisons’ and a recent influx of prisoners from England into HMP Berwyn, England now appears to be using Wales as a warehouse for its most troubled and vulnerable.

In response to the proposal to build a prison in Port Talbot in 2017, MP Liz Saville Roberts warned that it would turn Wales into a ’penal colony for English prisoners’. Much like nuclear power and open cast mines, ‘criminals’ and the families that visit them are made into undesirables, incarcerated in Wales to be kept from the sight of middle England. This project reveals a continuation of the extractive nature of the relationship between England and Wales, at the same time as it cements the status of prisoners as some of the individuals most marginalised by the state.

Much like nuclear power and open cast mines, ‘criminals’ and the families that visit them are made into undesirables, incarcerated in Wales to be kept from the sight of middle England.

HMP Berwyn, the newly built mega-prison based in north Wales, is the second biggest carceral structure in Europe. From the outset, Berwyn was marketed as a solution to uphold prisoners’ Welsh language rights and cultural sensitivities that had been undermined throughout the history of the British prison system.

The state used the wish to assert prisoners’ cultural rights to create an infrastructure that will tighten England’s grip on any attempt at Welsh control over the judiciary and expand the prison industrial complex. It has also since become abundantly apparent that such language rights don’t exist in HMP Berwyn from news stories of abuse reported by prisoners for speaking Welsh. In reality the criminal “justice” system is simply a reassertion of what Max Weber called the state’s monopoly on violence in his Politics as a Vocation (Weber, 1919).

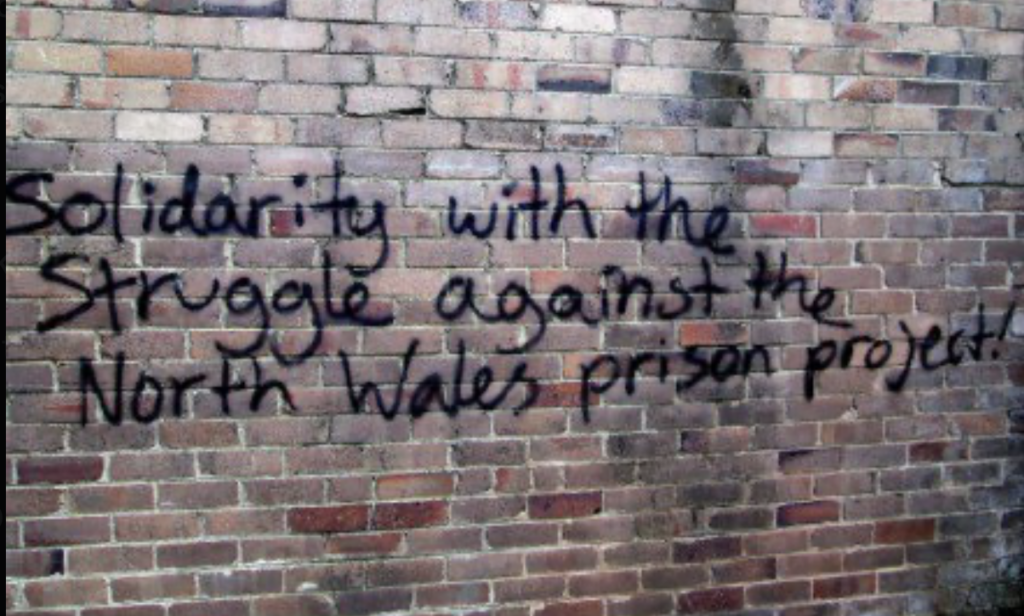

I was part of the campaign against building these super prisons. Research shows that the more prisons you build, the more the prison population will exponentially increase. The carceral system is becoming increasingly privatised; even publicly run prisons are not guaranteed to be in public hands forever, and most of the work surrounding the prison is carried out by private subcontractors for profit.

As the British government plans the biggest prison-building programme in generations, aiming to create 20,000 new prison places, this is a cause for serious concern. Thus far their plans have been a failure, partly thanks to grassroots campaigns, but prisons continue to be built; a 2021 report from Corporate Watch suggests there are plans to push for more.

The infrastructure of prisons is also a modern day women’s issue. There is currently no women’s prison in Wales. Women are therefore sent to prisons in England. This of course raises issues for their family, especially for these women who want to stay in contact with their children. Continued contact is crucial for prisoners to rebuild their lives upon leaving prison.

But as I mentioned earlier, building more prisons often results in more people going into prison. In addition to this, public transport infrastructure is so poor in Wales that if a new women’s prison was built it might be more difficult to reach than the prisons in England Welsh women are currently sent to. All transport infrastructure in north and south Wales tends to lead to England, and mid Wales is virtually a desert in terms of suitable public transport infrastructure.

What then can we propose? Some campaigners including No Births Behind Bars (who specifically focus on ending imprisonment for pregnant women) and even reformist charities like the Prison Reform Trust advocate for the decarceration of women. This is in light of the fact that the vast majority of women are in prison for nonviolent offences and pose no threat at all to others. The obvious answer is to not build a women’s prison, but to find restorative and transformative justice alternatives.

Gofod i drafod, dadlau, ac ymchwilio.

Cefnogwch brif felin drafod annibynnol Cymru.

What would the alternative look like? As someone with skin in the game, I’d argue it can only be prison abolition and a Welsh manifestation of libertarian communism – stateless socialism organised by workers and communities in symphony with each other. These are models that emphasise solving problems and preventing harm by providing for people’s needs and not taking the punitive route in dealing with harm.

It stands to reason that an authentically Welsh embodiment of justice wouldn’t be carceral, but rather reminiscent of the restorative justice laws of Hywel Dda. Dated and imperfect though they may be, these laws contained a general principle of community accountability, and reparations for harm caused. They were also interestingly much less patriarchal than other European laws at the time. Women could legally own property and ask for a divorce under certain conditions.

One example of abolitionism and community accountability in action is that of northeast Syria, known as Rojava in the Kurdish language. The Kurdish women’s movement has established over 62 Mala Jin, meaning ’Women’s houses’, that are a central part of dealing with conflict. The methods are diverse but the bottom line is that women are dealing with matters of harm and conflict in their own communities as an alternative to the criminal justice system.

There is evidence that these new justice systems, based on structures of reconciliation, preventative measures and restorative and transformative justice have led to a reduction in patriarchal violence, honour killings and even crimes such as theft.

The Zapatistas’ practice another revolutionary example of restorative justice. Interestingly the rationale behind this is also a consideration for prisoner’s families, as explained by the Zapatistas’ elected Honor and Justice Commission: ‘those who really suffer are the family members. The guilty just rest all day in jail and gain weight, but their families are the ones who have to work the cornfield and figure out how to survive.’

There’s a plethora of examples that hold far more promise than the continuation of the British legal system and mega prisons.

We don’t necessarily need to look at revolutionary contexts for examples of abolitionism. True abolitionism means centring people’s dignity, self-determination and building communities where people’s basic needs are met. Even in Europe and the USA, there are some examples of successful abolitionist non-reformist reforms. These kinds of reforms change prisoners’ living conditions in the here and now without further strengthening the prison industrial complex and contradicting the ultimate goal of abolition.

One example of this is the way Portugal, a country that once had the highest levels of drug-related deaths in Europe (and to a lesser extent Scotland) changed their approach to substance misuse issues from a criminal matter to a public health matter. Portugal’s decriminalisation of drugs radically changed the disturbing statistics around drug deaths and harms associated with drugs. The global campaign ‘Support, don’t punish’ also pushes for an abolitionist non-reformist reform, an important step toward a prison-free world.

In the wake of George Floyd’s racist murder by a white policeman, abolitionist and anti-colonial politics were made more mainstream by the Black Lives Matter movement. Public awareness of abolitionist politics has considerably shifted. As Angela Davis says in her prologue to the book Abolition: Politics, Promises, Practises, this explosion of education and action was a culmination of many decades of work, and did not appear out of nowhere.

In the USA, the group Critical Resistance was set up in 1997 and has since been making a strong contribution to this movement, working to offer practical alternatives. The documentary Visions of Abolition outlines the group’s journey and their project ‘A New Way of Life’. An ex-prisoner opens up her home to other women leaving prison, creating a healing and caring community and providing a stable base for these women to get their children back, and find safety and security in their lives. She also provides the women with educational workshops and a library to give them the tools to create a narrative around the causes that led to their imprisonment, removing stigma and shame.

Projects like these, which create a microcosm of healing where people’s emotional and material needs are met, are clearly transformative for their recipients. We witness these women build a better life and stay out of prison. Prevention is an essential pillar of abolitionist practice.

Generation 5 is another US-based abolitionist initiative led by survivors. Its long-term strategy is to end the pandemic of child sexual abuse in the USA within five generations. So far the prison system has failed to protect children from this terrible harm. Many perpetrators start out as victims themselves, and abuse can be a self-perpetuating machine.

In short, there’s a plethora of examples that hold far more promise than the continuation of the British legal system and mega prisons. People are being harmed and there are things people can do from the grassroots. We don’t need to wait for devolution of the criminal justice system or to wait for politicians to catch up with the evidence of what works in terms of making communities safer for all. As the above shows, their decisions are often not evidence-based but ideological.

In 2100 what if, therefore, instead of mega prisons, we had women and survivor-led justice centres?

As mentioned in the documentary Visions of Abolition, we can work now to crowd out the criminal justice system with alternatives. But we must remember those still being harmed and trapped in the system.

In 2100 what if, therefore, instead of mega prisons, we had women and survivor-led justice centres like that of the Mala Jin in Rojava? What if we had housing for all and self-organising communities that provided for everyone’s needs? What if we had a classless society and good healthcare for all?

The carceral system is so enmeshed in controlling the most impoverished in our society that the fate of our justice system and that of our humanity as a whole are inseparable. If communities all over Wales could make prison obsolete through self-organisation, crowding out the criminal justice system, we have the potential to smooth out the jagged edge and move towards a wholesale transformation of our society.

These are things people are doing and people can do right now. From transformative justice collectives to abolition education groups, from working in the community to support the most vulnerable people to supporting parents who are struggling, abolitionism can and is happening in our everyday lives, and it’s the key to a better Wales.

NB This article was written before the announcement of the general election – however, Labour do not diverge in any significant way from the Conservative in terms of their policies on justice. The paradigm is the same. They also seem to not favour the devolution of justice in Wales, therefore this recent election does not signal any change from the current status quo.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer. If you want to support our work tackling Wales’ key challenges, consider becoming a member.